Massachusetts, as you may have heard, is freaking out over plans to put 150 rattlesnakes on an island in the middle of the state’s biggest reservoir, yet here in New Hampshire we already have a Rattlesnake Island, on Lake Winnipesaukee.

Plus we have Rattlesnake Hill in Concord, as well as five other Rattlesnake Hills scattered across the state, not to mention four Rattlesnake Mountains and a Rattlesnake Pond.

What don’t we have much of? Rattlesnakes.

The only rattlesnake native to New Hampshire is the timber rattler, a shy species that New Hampshire Fish and Game categorizes as “critically imperiled.” State biologists say only a single den exists in the state with a population of perhaps three or four dozen snakes.

“We do surveys at historic sites and keep looking at other potential sites, and we still hold out hope that one day we’ll find another population . . . but as the years go by it seems less likely,” said Mike Marchand, wildlife biologist for Fish and Game, who has hunted around pretty much all the places with “rattlesnake” in their name.

The once-common timber rattler is rare in Massachusetts, too, which is why the Massachusetts Fish and Wildlife department proposes to put 150 timber rattlesnakes on an uninhabited island in the Quabbin Reservoir, where they can breed without fear of encountering people. (The concern involves people killing the snakes, not the other way around. As Marchand put it: “It usually doesn’t end in the snake’s favor when there’s an interaction.”)

That plan has generated headlines around the world ever since the Boston Globe broke the news, because who can resist a story with “rattlesnake-infested island” in the headline? At least some people living around the reservoir have gone public with concerns about the plan, a common reaction to anything involving snakes.

“I work with snakes and I work with turtles and I work with birds – and it’s a different reaction people have when you’re working with snakes,” said Marchand, who has no connection to the Massachusetts proposal.

Marchand hopes that the attention might lead people to reconsider an often-instinctive dislike of the timber rattler, which despite the fearsome-sounding name is shy and unaggressive.

“We certainly would like to do more positive PR for rattlesnakes. They’re misunderstood, and you see from the Massachusetts example, the negative press associated with them,” he said.

Marchand won’t say where New Hampshire’s rattlesnake den is, for fear of attracting collectors. That’s not an empty fear: Poaching snakes and selling them to collectors is a major contributor to their demise.

Infamously, a man named Rudy Komarek spent three decades poaching and selling timber rattlers in New England, taunting law enforcement and biologists all the while, and was responsible for wiping out a large number of the rattlesnakes in Connecticut and Massachusetts before he died in 2008 of a heart attack (not of a snake bite).

Even if the Quabbin Reservoir plan goes through, it will take a number of years. Snakes are being gathered from three different populations and will be cross-bred at Roger Williams Park Zoo in Providence, R.I., to establish genetic diversity before they are brought to the island.

There is no equivalent plan to create new breeding populations in New Hampshire, says Marchard, although the snake certainly could use some help.

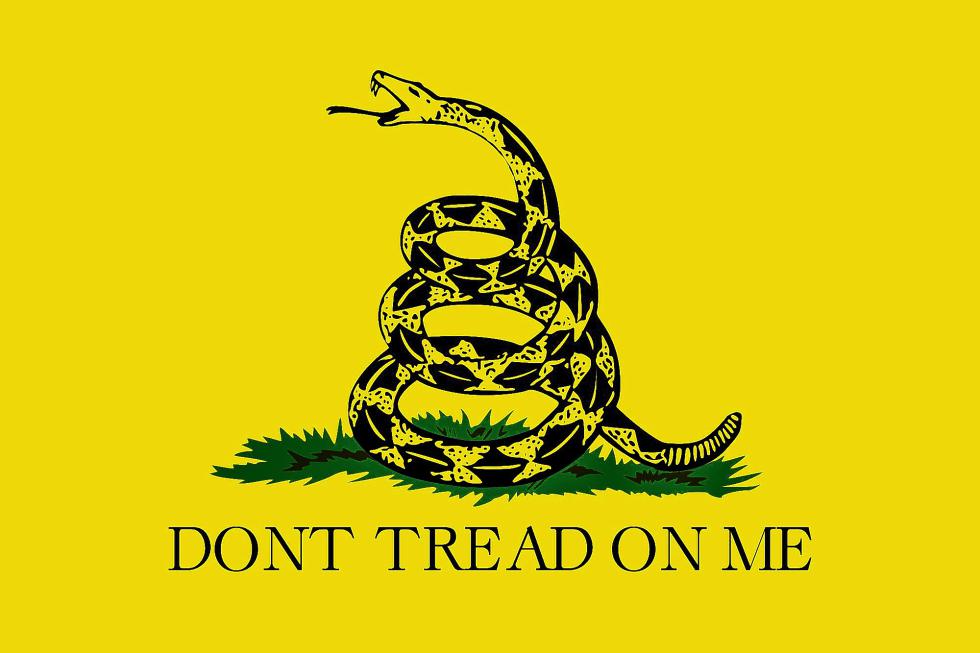

The timber rattler didn’t used to be so hard to find: You can even see it on the “Don’t Tread of Me” flag of colonial America, made prominent in recent years through its adoption by the Tea Party political movement. The flag features a coiled timber rattler, chosen because it was the venomous snake most often encountered by early settlers to what is now New England and the mid-Atlantic states.

Despite that veneration, however, people wasted no time trying to wipe out the venomous serpent.

Concord’s Rattlesnake Hill got its name, according to The History of Concord by Nathaniel Bouton, “on account of the snakes of these species that formerly had their dens there.” The key word is formerly: Even though the book was published back in 1856, quarry men who wanted snake-free access to the hill’s rich veins of granite had already made the timber rattler a historical footnote.

They lasted longer on Rattlesnake Island. A 1975 history of Lake Winnipesaukee by Paul Blaisdell said that within living memory, “It was possible to follow down the east shore of the island in a small boat on a bright, clear day, and see one or more snakes on the ledges in the sun. During lumbering operations on the island workmen have been bitten by them.”

However, the book went on, “On at least one occasion the island was burned over in an effort to exterminate them, once and for all.” No snakes have been seen on the island for decades.

Timber rattlers once lived throughout the eastern U.S. but are now endangered almost everywhere. That’s partly due to being actively killed off – some states paid bounties for dead rattlesnakes as late as the 1980s – and partly due to development which encroaches the woody, rocky, isolated areas that they like.

There is also concern about a fungal skin disease that was first spotted in timber rattlers in northern New England but has now been found in a number of different snake species, Marchand said.

They are so imperiled that they have become one of the species targeted by the Orianne Society, a national group that seeks to protect amphibians and reptiles.

It’s obvious why people would want to get rid of poisonous snakes, but why would we want them around?

Partly because they’re beautiful, but also because they are important predators of small mammals and rodents, including the mice that carry the ticks which spread Lyme disease. When we remove an animal from the environment, especially a predator like snakes, we cause ripple effects that are hard to predict.

It should be noted that some skeptics think New Hampshire has many more rattlesnakes than Fish and Game admits, but evidence for those claims is hard to find. There was a flurry of news in 2012 when an apparent timber rattler was found in a garage in Raymond, but it could have been an escaped pet or one of a couple of nonvenomous species that imitate rattlers to scare off predators.

Whatever it was, no other timber rattlers were reported.

It will probably be a long, long time before anything new in New Hampshire gets christened with rattlesnake in its name.

(David Brooks can be reached at 369-3313, dbrooks@cmonitor.com, or on Twitter @GraniteGeek.)

Return to the Concord Monitor

Return to the Concord Monitor

ALL SNAKES SHOULD BE ELIMATED THEY SERVE NO SPECIAL PURPOSE EXCEPT TO BITE AND KILL PEOPLE

As the article says, snakes keep the rodent population in check. What will people do without snakes? There might be some plagues from rodents getting out of control and getting into the human living areas. There is always a purpose for every animal, that keeps the circle of life healthy..

Snakes keep the animal population in balance. Imagine how many rats and mice we would have living in our houses if we didn’t have snakes to keep them under control? Snakes are also helping to create medicines that help people. Researchers are testing the potential cancer-fighting properties of certain snake venoms.

Note: I killed off a couple of responses to one comment because they didn’t discuss the issue, but discussed the person who commented.

You know the sort of thing: Not “your opinion is wrong because of X” but “you are an idiot because you think X”.

We’ll leave insulting those you disagree with to the political sphere, if that’s OK.

Why was the initial comment left when it doesn’t state any issue, or intelligently debate this – just yells at everyone his opinion with no basis to back it up? This is just an argumentative post. Snakes absolutely serve a purpose in nature or would not be there. The more humans intervene and kill off creatures that serve a purpose in nature, the more nature becomes off balance and humans will notice the ill effects. We have encroached on the forests and streams where these creatures thrived so we could build homes in the woods, and now we complain and feel the need to kill of the creatures we don’t like living near us. If we kill the snakes, we then have mice in our homes and hire exterminators to kill off mice populations. If we don’t like bats, we kill them off and have bugs that carry diseases. We need to learn to let nature be and enjoy it and live amongst it – or go live in a NYC high rise.

It was left in because it didn’t insult anybody. Maybe it wasn’t useful, but it wasn’t deletion-worthy.

I am “somewhat” LEERY of snakes,and getting bit. However, when I hiked the Appl.trail, I choose the colder winter months. I can manage minus -30F, but do no hike , if can help it, when it’s over 70-deg/ F. 73,and still going strong. BTW, When I go To the Alaskan islands to photograph Brown Bears, I carry a rifle that would disembowel a V-8 engine. Can’t be too careful. Lou

I Agee we must learn to live with all creatures we had snakes in calif. We never killed them just moved them back to hills and grass lands

I was hiking in N.H. this week and heard the sound of a rattlesnake as I approached an outcrop of boulders. I was coming down off the outlook of Boulder Loop on Kancamagus Hwy and the sound came from the part of the trail that was surrounded by walls of boulders. The second place was off the Arethus Falls trail in Crawford Notch State Park. We reached the part of the trail that has large boulders and off to the left we heard the sound of a rattle as it approach the boulders. an