This article will appear in the Monitor at some future date (it’s a “floater” – an article with no timeliness that can be held until we have room for a good presentation in print), but rather than wait, here’s an unedited version for you newsletter readers. If you spot any typos, let me know. – David

To answer a question about New Hampshire’s digital road signs that’s probably on your mind: No, they’re not going to become amusing like they are in Maine (“Love is blind, driving is not – focus, people!”) or have fake accents like in Massachusetts (“Changing lanes? Use yah blinkah”).

But to answer a question that’s probably not on your mind: Yes, they are another step toward transportation geeks’ dream of creating a “smart road.”

“We have to get much more efficient in how we use our roads,” is how Bill Boynton, spokesman for the Department of Transportation, puts it. “The days of just adding lanes, adding miles of roadway, are over.”

These big, permanent digital signs are cropping up all along our interstates and turnpikes. We have 52 so far, with more coming, including the first non-limited-access-road sign slated for Route 101 in Bedford.

New Hampshire has been installing the signs for a few years and has no plans to stop. The next upgrade will happen along the F.E. Everett Tunrnpike between the Massachusetts border and Concord, as part of a $4.2 million upgrade of the road’s IT infrastructure.

That’s all fine and dandy – but why can’t we see more humor on them?

No jokes please, we’re New Hampshire

Blame the feds, says Susan Klasen, who oversees the Department of Transportation’s Traffic Management Center on Route 106 in Concord.

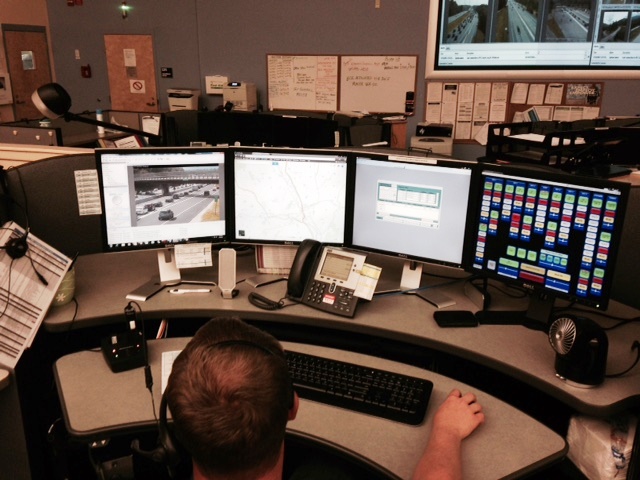

The N.H. DOT controls the signs, as well as traffic cameras and other networked highway devices, from this futuristic-looking room, which is dominated by a video screen bigger than most backyard swimming pools. But it must operate within rules set by the Federal Highway Administration about what is suitable to show to people who are hurtling along at 70 mph.

Courtesy photo: Just look at all those screens!

For some reason, Klasen said, the federal officials in New Hampshire have proved less amenable than their counterparts in neighboring states to veering away from straightforward messages like “Winter storm tomorrow morning– be prepared” or “Exit 6, 21 miles, 20 minutes.”

“No phone numbers, no web addresses, no ads – and no jokes,” said Klasen. “Bill (Boynton) will call me and say, ‘Look what they have in Maine!’ – and I’m, ‘Yeah, we can’t do that’.”

These signs are officially labeled “variable-message” (or “dynamic-message” or “changing-message” – take your pick) and over the past decade have become part of the standard arsenal of tools for traffic control.

Many are portable, used by construction sites or local police departments – as a side note, those are relatively easy to hack into, which is why they sometimes read “Zombies Ahead!” or other prank messages – but we’re talking about larger, permanent signs overhanging highways.

They can display three lines of text capable of up 20 characters each, making them slightly less than half as long as a Twitter post, and under federal rules concerned about driver distraction can shift back and forth between just two messages.

Traffic Management Center

The messages are controlled by operators at the Traffic Management Center, a huge open space also used by the state police, which makes it much easier to share information, and in the same building as Homeland Security, which is helpful for communication during weather and other emergencies.

The messages on the signs are controlled by seven full-time and four part-time employees, plus managers as needed, at one of more than half-a-dozen work stations, most of which use five computer monitors at once.

Using software known as Compass, each workstation can select a particular sign and either type in a message or choose from a number of pre-loaded messages, then send it to the sign and assuming there’s a nearby traffic camera (there usually is), see it displayed within a few seconds. Signals get to the sign in various ways; some are connected with fiber-topic cables, some via modems, and some with microwave signals.

Internally, said Klasen and Nick King, operations supervisor at the center, the big change was new software that consolidated systems used by the police, DOT and others. Formerly messages had to be phoned in, or scribbled on paper and carried from desk to desk, but now they can go from being approved to being displayed 100 miles away in just a few seconds.

There are protocols for what can go on signs, explained Klasen. Messages must generally be approved by police or highway officials, to make sure it’s accurate and useful.

“The accident, is it northbound or southbound (lane)? Which mile marker exactly? Which lanes?” she said, as examples of the details needed by sign controllers.

Traffic cameras can help show controllers what’s happening, although part of the protocol is to swivel them away from accidents, both to give privacy to people who might be hurt and because the Traffic Management Center cares about what’s happening to cars heading toward the crash.

The signs’ default message is often generically cautionary, reminding you to buckle up or not drive and drive, but increasingly it gives travel times to a nearby exit. That travel time is automatically updated by TomTom, the GPS company that has a major presence in Lebanon, which calculates it from information received from its systems in use in cars and mobile devices on the highway with historical and other data.

The real value of the signs comes when they warn drivers of accidents or construction-related lane closures ahead, using information sent from the state highway department or the state police. Also of value are cautionary notices, such as when speed limits are lowered due to poor visibility or, using sensors known as RWIS or Road Weather Information System, warning motorists of dangerous conditions ahead, such as slick roads. (RWIS bounces different signals off the road to measure such things as depth of water on the pavement and percentage of ice in the water, calculating a friction coefficient for the highway.)

Drivers can use this information not only to be safer but to change their route on the fly. This is a key part of the “smart road” concept – instead of highways being passive surfaces they become information systems that help guide travel, with the hope that more people can make use of them, doing it more efficiently and more safely.

Getting information to drivers

That requires not only collecting information but getting it to the drivers, which is the where these variable-message signs come in.

But a large immobile message board is hardly the end of this process, as King acknowedeged.

“This is the device that matters,” he said, gesturing at a cell phone while demonstrating the messaging system to the Monitor.

New Hampshire DOT is already sharing information with Waze, a free GPS navigation program that takes accepts reports and updates from its users via cell phone to improve real-time traffic information. (Google, which owns Waze, uses this data in its Google Maps traffic information.) The state gets information from Waze to improve its reports and sends information to Waze to improve information used by drivers when deciding when and where they want to travel, said Klasen.

There’s a limit to this, however. After all, transportation officials don’t want to encourage drivers to worry about reading and using a mobile device when they’re behind the wheel.

New Hampshire has joined with Vermont and Maine on NewEngland511, a regional subset of the national traffic-information system. This web-based service at www.newengland511.org displays roadwork, accidents, emergency notices – plus all of the variable-message signs in the three states, in case you don’t want to be surprised before hitting the road.

Expect more information to be added as technology changes – as do expectations.

“This used to be new, but I think it has become something that people expect,” said Boynton.

Just as long as they don’t expect jokes.

Return to the Concord Monitor

Return to the Concord Monitor

In the sentence “There are protocols for what can go on signs, explained Klasen. Messages must generally be approved by police of highway officials, to make sure it’s accurate and useful.” should that read ‘by police OR highway officials”?

Indeed it should.

“The signs’ default message is often generically cautionary, reminding you to buckle up or not drive and drive,…” Not drive and drive, Dave?

Don – you’ll be happy to know the copy desk spotted my stupidity and fixed it for print.