Firearms season for deer, which by far the most popular hunting season in most of the country, started Wednesday in New Hampshire. Why Wednesday? And why can hunters kill certain genders at certain times, and more deer in certain parts of the state than other parts?

It’s an effort to keep a “healthy” deer herd in New Hampshire, as explained in this article written by N.H. Fish and Game biologist Dan Bergeron.

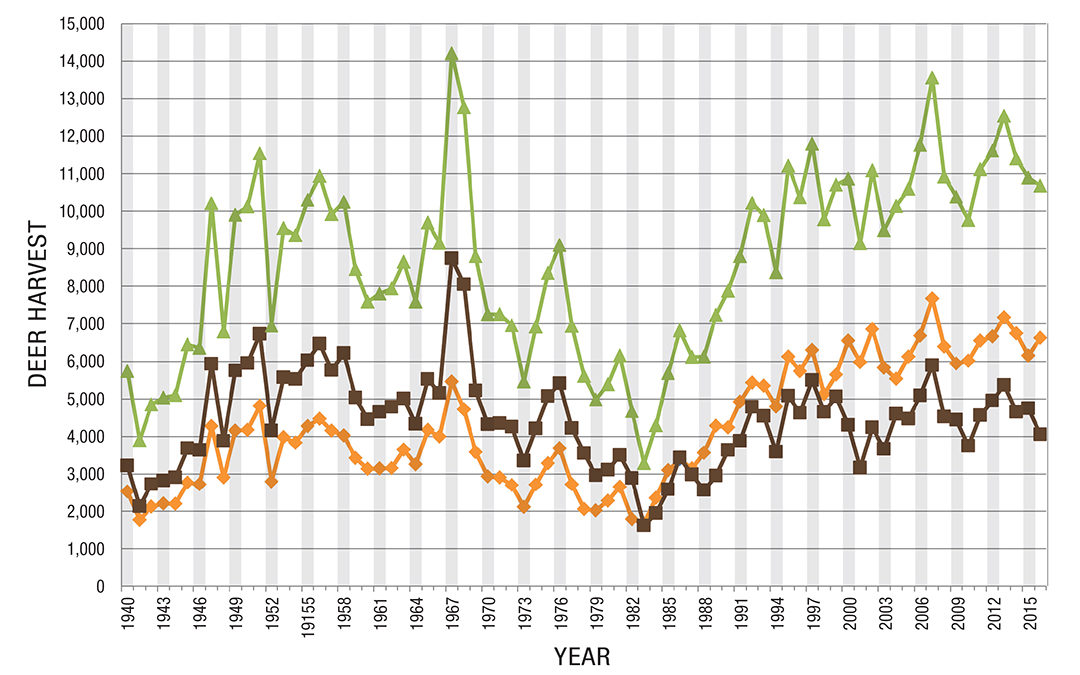

Prior to the early 1980s, deer seasons were set by the Legislature. For the most part, management of deer consisted of a north/south split of the state and an open or closed season (dice rolling may or may not have been involved). This led to drastic population declines following a series of severe winters and overharvesting of female deer. In 1983, a total of 3,280 deer were harvested statewide, the lowest deer harvest in the state since the 1940s. Around this time, management authority was handed over to the Fish and Game Department, and a more focused, scientific approach to deer management was established. Since then, the state’s deer population has increased dramatically; harvests now average close to 11,000 deer a year.

The article goes into some detail about the process, such as this:

This line of reasoning ignores some basic principles of population dynamics. That’s because mortality can act on a population in two different ways: it can either be compensatory or additive.

Compensatory mortality means that one source of mortality (say, hunting) compensates for another (e.g., severe winter). When working together, the two sources of mortality won’t increase the overall mortality of the population (e.g., what you kill during the hunting season would die during the winter, or from some other cause, anyway).

Additive mortality means the two sources of mortality add to one another and, when working together, will increase the overall number of deer deaths. In other words, what is killed during the hunting season is in addition to what dies during the winter or from other causes.

In reality, mortality sources rarely fall neatly into just one of these two categories. Hunting mortality may be largely compensatory during years with milder winters, but it is certainly additive during years of more severe winter weather. That means deer killed during the hunting season are most likely going to be in addition to deer that die during winter. Also, while winter mortality primarily affects the young (fawns) and the old, antlerless harvest mortality primarily affects adult does, the source of future fawns, and can slow population recovery following a severe winter.

Life sciences – they sure can be complicated.

Return to the Concord Monitor

Return to the Concord Monitor