It sounded like a heavy truck rumbling past or a load of snow sliding off the roof, depending on your point of view, but Monday’s small earthquake near Contoocook was actually a reflection of how quiet New Hampshire is, earthquake-wise.

“Why don’t we have more earthquakes? We’re not on a plate boundary,” said Margaret Boettcher, UNH assistant professor of geophysics, referring to the massive tectonic plates that carry the planet’s continents as they float on underlying layers of hot magma. Most of the world’s earthquakes are felt where these eight or so plates meet, occurring as tectonic plates collide or slide over or under each other.

“We’re in the interior of the North American plate” and thus relatively stable, said Boettcher.

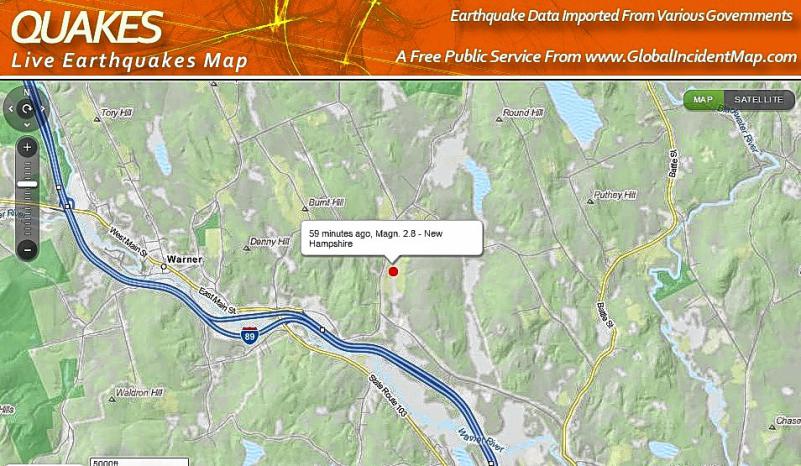

Monday’s earthquake, which measured 2.9 on the Richter scale, occurred at 9:18 a.m. and was centered near the Warner-Hopkinton line. It originated about 5 miles deep, which Boettcher said is a typical depth for earthquakes. Similar quakes occur “probably on average about once a year in New Hampshire,“ Boettcher said.

No damage or injuries was reported. As of mid-morning, 124 people had registered at the “Did you feel it?” section of the USGS Earthquakes Hazard website (http://earthquake.usgs.gov/data/dyfi/). The strongest report on the modified Mercalli intensity scale, which judges how much the earth moves, was a five out of 10, classified as “light shaking.”

Such reports are useful to scientists even though they’re not quantified by scientists, Boettcher said: “People are actually quite good seismometers in terms of intensity.”

New Hampshire has never had a reported fatality from an earthquake, and fewer than a dozen temblors in history have done serious damage to buildings. But when there are earthquakes in the state they often happen in central New Hampshire, on a zone stretching from the Contoocook area to the Lakes Region.

“There’s a zone of weakness in central New Hampshire most likely was caused by when the Atlantic opened, 200 million years ago – all of the stress imparted on our rocks is slowly being relesed over time. We’re not certain that’s exactly why all the earthquakes occur in this area, but that’s likely to be a part of it,” said Boettcher.

When earthquakes do happen, we feel them. “In the eastern part of the U.S. we have pretty cold and hard rocks, so earthquake waves do propagate efficiently. When one occurs, we can feel it further away and feel it more strongly,” Boettcher said.

The most recent new Hampshire earthquake of any serious magnitude was centered near Lake Ossipee in December, 1940.

All this is not to say that a big earthquake is impossible here. One of the strongest earthquakes ever recorded in the U.S. occurred near New Madrid, Missouri, on the Mississippi River, in 1811, even though that area is not near a plate boundary. Boettcher said that strong earthquakes are also possible along the Saint Lawrence Seaway in Quebec, and historically have been strong enough to be felt throughout the state.

“Given there was a 6.5-ish earthquake in (New Hampshire) in the past, we think that something could happen here,” Boettcher said. Don’t expect predictions, however: Temblors in the interior of plates are much less understood that temblors at the edges of plates: “We have no idea what the recurrence area could be.”

And even four centuries of reports dating back to Colonial days doesn’t really help.

“400 years is extremely small (time span)” for geology, Boettcher noted.

Return to the Concord Monitor

Return to the Concord Monitor