I have a fairly long driveway next to an open field, and at least once every winter, snow drifts across it to the point where things get dicey without all-wheel drive.

For two decades, I have talked about setting up a snow fence to keep out the drifts, but I’ve never gotten around to it. Which, I recently learned, is a good thing, because I would have done it exactly wrong.

One consolation: Many people do it exactly wrong.

“I see it a lot. People don’t understand how a snow fence works,” said Robert Haehnel, a research mechanical engineer at the Cold Regions Research and Engineering Laboratory in Hanover, an Army Corps of Engineers facility that studies anything that freezes. (Known as CRREL, it gets my vote for Most Interesting Place in N.H. That You Didn’t Know About.)

“For years, one of my neighbors had . . . that orange snow fence and posts, they put it right next to their driveway, perpendicular to the wind. And every year when the wind started blowing, the entire hillside would be deposited on their driveway,” he said. “They finally gave up.”

So what did they do wrong? At my request, Haehnel walked me through years of research on snow fences, much of it done by a man named Ronald Tabler who wrote the field’s bible: Controlling Blowing and Drifting Snow with Snow Fences and Road Design.

The manual is used by most states, including New Hampshire, to guide placement of snow fences. If you want more details you can easily find it online, all 307 pages of it.

So here’s the most surprising thing: Snow fences don’t stop drifts by blocking the snow that’s blowing right along the ground, as I had envisioned. They stop drifts by disrupting the aerodynamics of the wind passing overhead, slowing it down so it can no longer carry all the flakes it had picked up.

What this means is that snow doesn’t pile up behind a fence, it drops out of the sky in front of the fence – that is, on the downwind side. So if you place the fence next to your driveway, as I planned, you’re guiding more snow to fall right down onto the driveway.

It’s like a snowdrift multiplier!

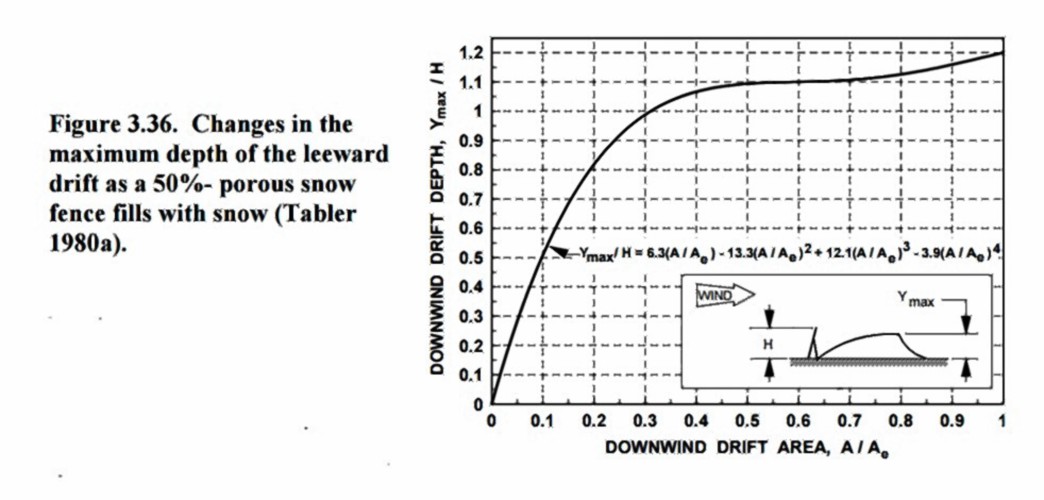

Tabler even developed a rule of thumb for placing fences. Take the height of the fence and multiply it by 35, and that is the distance you need between the fence and the thing you want to protect, to ensure all the snow will fall out of the air before the wind gets to the target.

For a standard 4-foot snow fence, that equals a distance of 140 feet away. Holy Toledo – that’s a long way.

If you’ve ever seen a snow fence sitting forlornly in the middle of a field, now you know why.

But wait, there’s more. Tabler found that snow fences need a certain “porosity” – holes to keep snow from piling up and knocking it over – and should have a gap at the bottom equal to 10 percent of the height (about 5 inches for that standard 4-foot fence).

Why the gap? It directs some of the wind under the fence and scours away snow that might build up in front of the fence. This matters because the height of the fence above snow determines how well it disrupts wind passing overhead – so if snow builds up in front, your fence becomes effectively shorter and works less well.

“Make sure the bottom doesn’t get buried over time. If it starts out a 4-foot fence and you get a foot of snow, now it’s a 3-feet fence. . . . Every time it gets buried, it’s less effective,” Haehnel said.

Some places, notably Japan, build large snow fences with gaps designed to scour snow off roads when there isn’t room to place the fences at the right distance. This works well, Haehnel said, but has the side effect of increasing the speed of the wind to the point that it can be dangerous for vehicles.

Snow fences can also be used to collect rather than deflect snow, Haehnel said. “An example is setting snow fences upwind of a cattle pond, so you deposit all the snow there. When it melts, you’ve got a water supply for your cattle.”

So there you have it: A boring, overlooked aspect of life in wintertime is actually complicated, counterintuitive and interesting.

I’ll take solace in that the next time my car gets stuck in the driveway.

Return to the Concord Monitor

Return to the Concord Monitor