If you need help gathering tons of insects to determine whether bad bugs are invading our woods, you could do a lot worse than enrolling a thousand night-flying acrobats to do it for you.

Even if the only way to get results is to perform DNA analysis of their poop – sorry, I mean their guano.

“Getting access to samples is the most challenging part of much research fieldwork,” said Jeffrey Foster, an assistant professor in the University of New Hampshire Department of Molecular, Cellular & Biomedical Sciences (man, department names are longer than I remember as a student).

“With bats, we have the ability to get them to do the collection for us. They sample a particular area around their roosts. We just have to find their roosts.”

Happily, as anybody with a barn knows, finding a bat roost is pretty easy: Look for a guano pile on the floor.

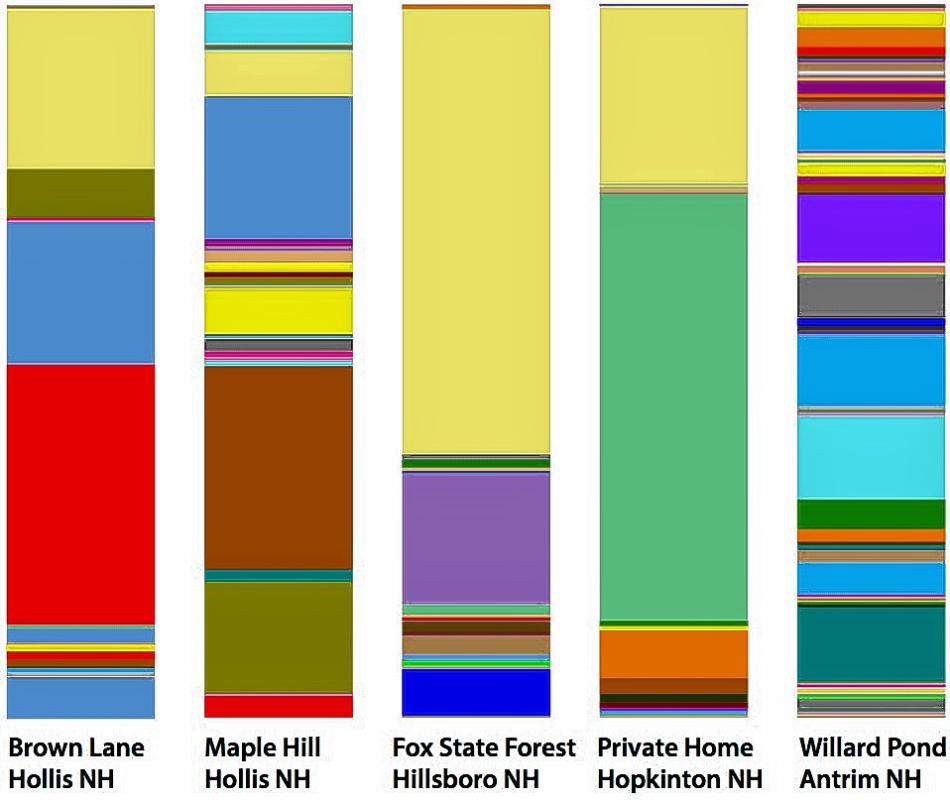

That’s what Foster and Devon O’Rourke, a Ph.D. candidate in Foster’s lab, did last summer, via a list of bat watchers previously collected by New Hampshire Fish and Game. They eventually lined up 11 volunteers who had bat roosts on their property and who volunteered to collect guano in a pilot of a project to use bats as sentinels to help alert us to the arrival of invasive insects.

Collecting bat guano for science doesn’t sound too bad, actually. Certainly no worse than many farm chores.

“You get a sheet of plastic, put it where pile had been. Let it accumulation for a week, then use the kit we sent, with 1.5 (milliliter) tubes filled up with a preservative solution, and put a pellet (of guano) in each tube,” said O’Rourke. “We use the preservative so volunteers didn’t have to worry about freezing it. We didn’t want to ask them to put bat poop in their freezer.”

Then they just mail the tubes to the UNH lab, clean off your plastic sheet, and do it again a week later. Continue weekly until the bats settle down for the winter.

At UNH, O’Rourke says, the samples are pulverized in a “glorified paint shaker” that turns them into “guano dust,” a system O’Rourke developed because the usual method of preparing samples for DNA analysis via chemicals or heat didn’t work well. “I think a lot of the insect parts were so hard, the exoskeleton was preventing the chemical degradation from happening,” he said.

After processed via the gene-analysis workhorse of PCR, which amplifies genetic sequences, comes the tricky part of figuring out what insects were excreted by the hungry flying mammals.

O’Rourke explained that most insect and spider species can be identified via a specific region of the genome called CO1, as long as the correlation between species and sequence has been made by some lab. ”We compare to a large reference database called BOLD. . . . Maybe up to a quarter of the sequences can identify to species already. There’s no prefect database for all insects.”

Sometimes the sequence is too poor to be useful, “sometimes the sequence info is high quality, a good read, but we don’t know what it belongs to.”

But often there are good results, which makes Foster shake his head when he looks back on his own doctoral research years ago, before cheap genetic sequencing was available, analyzing bird poop in Hawaii to see what insects they eat.

“At the time, one had to spend a lot of time under the microscope, hours and hours, looking at insects and spiders (from feces or stomach samples) – tens of thousands of parts. You can do it, but it takes a really long time and it takes a lot of expertise,” he said.

“I almost cried the first time I saw Devon’s work. He was able to do in a week in a half what had taken me two years to do, and his results were way better than mine.”

The point of all this effort is to take an existing practice – gene-sequencing bat guano to study what the mammals are eating – and give it a new goal.

“The only idea that was mine is using it for invasive species detection in the forest,” O’Rourke said.

As you know, insects from other parts of the world, such as the emerald ash borer or the Asian long-horned beetle, can show up and wreak havoc on our unprepared trees. The usual method of seeing whether such pests have arrived is to put out pheromone-scented traps, but that often succeeds only after the population is too well-established to eradicate.

“You’re detecting the forest fire, when you really want to look for the smoke. You can’t find the marginally small amount of invasives when they’re first moving in (with traps),” O’Rourke said.

With enough bats doing sampling, New Hampshire has a better chance of spotting an infestation early enough to avoid the scenario that hit Worcester, Mass., which in 2008 found an Asian long-horned beetle presence that had been lurking so long 27,000 trees had to be cut down to keep it from spreading.

Foster and O’Rourke, using funding from various forestry-related sources, are looking to expand the project this summer. If you’ve have bats on your property and think you can help, contact O’Rourke at devon.orourke@gmail.com. You can find more at the website for Foster’s lab.

Their only request is that you be ready to collect guano week after week all spring, summer and fall.

“We’re really needing commitment. It’s only 5 minutes a week, but for multiple weeks,” O’Rourke said.

And just think how fun it will be to hand over the mail-back box at your town post office and say, “Be careful with this; it contains bat poop.”

(David Brooks can be reached at 369-3313, dbrooks@cmonitor.com or on Twitter @GraniteGeek.)

Return to the Concord Monitor

Return to the Concord Monitor

Barn in Davisville, NH has bats, i will be happy to collect droppings