If it sometimes feels like your whole life has moved to your smartphone, New Hampshire has an update: Your death is moving there, too.

As we speak, the New Hampshire Division of Vital Records is launching the country’s first smartphone application that will let doctors, nurses and funeral directors file certificates of death without scribbling on paper or sitting at at desktop PC.

“Physicians wanted it to be more convenient, so we put it right on their hip,” said Stephen Wurtz, who as the state registrar of vital records has control over four centuries’ worth of Granite State births, marriages and divorces, as well as almost 12,000 deaths last year.

The immediate effect of going mobile with what’s called eCoD – as in “electronic cause of death” – will be greater efficiency. But a bigger payoff for public health should follow because instantly putting causes of death into accessible databases can help us spot problems early.

Officials have long kept an eye out for, say, an uptick in deaths due to respiratory illness in the Lakes Region (Is this a new disease?) or a sudden rise in opioid overdoses along the Massachusetts border (Is this a new drug?). However, it now takes days or weeks for that information to percolate to the proper officials. With the eCoD app, that should speed up.

“In almost real time, we can share this cause-of-death information with New Hampshire’s health department or the CDC, so if they’re doing surveillance, looking for any (outbreak), they can say, ‘It looks like we’ve got a pocket of something’ . . . and do more,” Wurtz said.

This benefit is the main reason that the national Centers for Disease Control and Prevention paid New Hampshire to develop the app at a cost of roughly $200,000, and is covering costs as we teach other states to adopt it, too.

The public tends to know the Division of Vital Records for its old-school genealogy room in its Fruit Street offices, where you can ponder written documents dating back to 1640 and indulge your library nostalgia by using a card catalog, it has been pushing the digital envelope for a long time.

“We’ve been registering events through some type of an automated system since back in 1988,” said Wurtz, who as a funeral director knows the hassles of filling out forms.

“New Hampshire was always on the leading edge of automation,” agreed Vijay Mishra, senior vice president of federal programs at CNSI, the company that made the app.

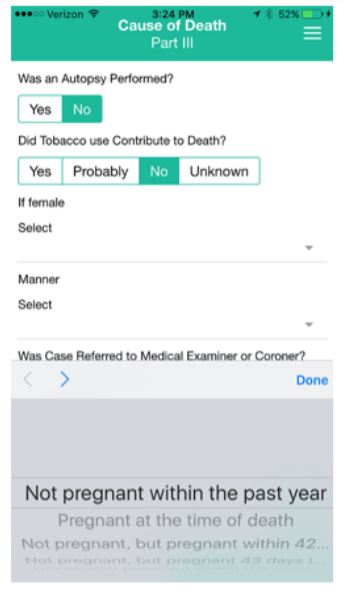

The company’s goal was to duplicate what is already done on paper – most of which is required in great detail by various laws – with digital improvement.

For example, if a physician clicks a box saying a death was accompanied by an injury of any kind, the software automatically reminds them that the certificate of death must then be filed by the medical examiner’s office following an investigation. If a physician is unsure whether the medical examiner should get involved, they can get hot links to phone numbers to call and find out more.

“A physician who puts down ‘died of lung cancer’ will get prompts, which may be ‘Where’s the site, the lobe?’ It helps drive down into the detail necessary to really understand what happened: ‘Lung cancer’ is just too generic,” Wurt said..

Similarly, if a physician types DM as cause of death, using a long-accepted medical abbreviation, the software will double check that they mean “diabetes mellitus” and then expand the term. If they type COPD, the software will use pull-down menus to make them be more specific about what type of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease was involved.

“One of the things in medical certification is we don’t want abbreviations, because abbreviations can be misinterpreted. But physicians liked the fact that they can still use abbreviations. Plus, they spell it right,” Wurtz said.

Spelling is one bugaboo for medical staff and funeral directors, while another is handwriting.

“We’re very good at deciphering handwriting,” said Heather Bentley, who oversees death records. Bentley has been at the job for 33 years – edging out Wurtz’s 32-year tenure – and says the current technology is a dream come true for keeping track of roughly 3½ million different documents.

She hopes that the app will help death certificates, which are a vital records laggard in terms of being electronic. Birth certificates, for example, have been all-online since 2000, but roughly 75 percent of death certificates are still filed on paper and must be electronically re-filed by the state, partly because the forms tend to be filed by harried medical professionals. Making the process mobile should help cover that shortfall.

By the way, the fact that the eCoD app is available at the Apple and Android app stores doesn’t mean you and I can report our brother in-law as having expired due to jealousy of our good looks. The app can only be used with accounts created by the Division of Vital Records, which first ensures that you’re a real physician, medical official or funeral director. Sorry, pranksters.

Return to the Concord Monitor

Return to the Concord Monitor