I am writing a column about arsenic naturally occurring in new Hampshire groundwater, so I thought I’d rerun this 2012 column I wrote for the Telegraph:

You think you know New Hampshire? Yeah, me too. So why don’t we know about the Massabesic Gneiss Complex?

It’s bigger than Lake Winnipesaukee, older than Mount Washington and indirectly affects as many people daily as Route 101A. Yet I can barely say it, let alone understand it. (Gneiss, a type of metamorphic or melted rock, is pronounced “nice.”)

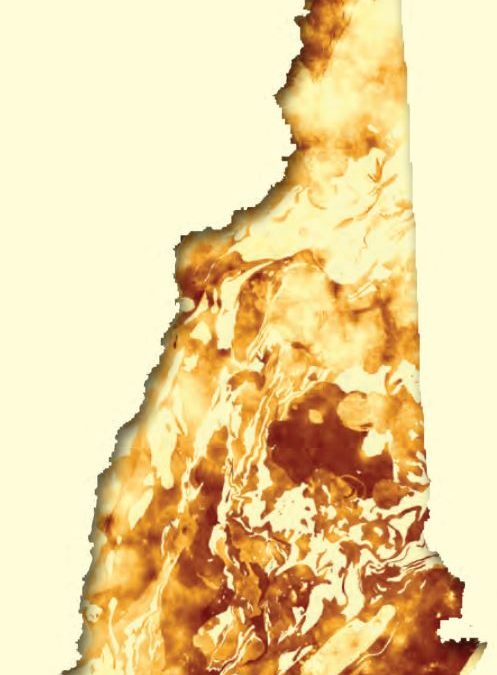

I became aware of this massive, intriguing object indirectly, after the U.S. Geological Survey released a study Dec. 5, 2012, about arsenic in New Hampshire well water. The study found that arsenic is likely to be found in groundwater at low to moderate levels or higher in almost 40 percent of New Hampshire.

“We were surprised at how much of the state was affected,” said USGS scientist Joe Ayotte, who led the study and who was a panelist for Science Cafe New Hampshire in May, when we discussed the topic. “Before, I would have told you that arsenic is an issue in southeast New Hampshire parts of the Concord area, Lakes region. Now I’m thinking, huh, it’s just about everywhere.”

One place arsenic isn’t, however, is over the Massabesic Gneiss Complex.

On a New Hampshire map shaded to show the presence of arsenic in wells, the complex stands out like somebody had left their finger on a photograph while it was being developed in the darkroom. (That analogy will baffle people younger than 15.)

The complex shows up as a pale swath that extends northeast from Brookline, Mason and Hollis, missing Nashua but passing through much of Amherst, Merrimack and Bedford, then just missing Manchester until it peters out past Candia, around Pawtuckaway State Park.

When I saw it, I got intrigued so Ayotte passed me to Rick Chormann, who has the wonderful title of state geologist.

“It’s very old: 620 million years old, into pre-Cambrian era. This is deep time; it’s very old basement rocks,” Chormann said in a phone interview. Pre-Cambrian, as you may recall from school, almost means pre-life-on-Earth. Before then, only one-celled creatures existed, so we’re talking wicked early.

Yet this very old rock is so close to the surface that it affects drilled wells and is even visible in some places. Chormann says you can see the complex’s “beautiful” striations, caused by millennia of melting, folding and remelting of rocks, in some of the new road cuts made by the expansion of Interstate 93.

“They’re pretty complex rocks, they’ve been though a lot,” he said. “There have been, we think, three major episodes of melting. … There are some very dark bands and some light bands, a lot of swirly layering within it.”

This age, he said, helps explain the lack of arsenic.

“While time is cooking these rocks up, deforming them, a lot of the chemical elements are getting mobilized and essentially moving upward. … Whatever arsenic might have been present in the original metaseidmentary rocks very likely was driven off and eroded away,” said Chormann.

Further, because these rocks have been melted so many times, they are tightly formed with relatively few fractures that allow water to seep through. Drilled wells over the complex often have to be very deep in order to tap into enough water flow to be useful.

“A lot of deep, low-yielding wells are associated with the Massabesic,” said Chormann.

This factor also could contribute to the lack of arsenic because there’s less interaction between water and rock than found in formations with lots of cracks.

“The chance for groundwater to interact chemically with that formation is limited,” said Chormann.

In other words, the complex’s appearance on the arsenic map reflects a geological reality that affects the health of us living above it.

So where did it come from? Chormann said there is still much debate about the origins of the Massabesic Gneiss Complex, but the most likely scenario is that it came to its present location during the Taconic orogeny, a period of mountain-building after the Iapetus Ocean (a sort of Atlantic Ocean predecessor) closed up. For some reason, a portion of the basement rocks – I love that phrase – poked up so far it can still affect the various bits of organic matter that are scuttling about on its surface.

This is an example of how much of our daily life is affected by geological actions of enormous size and mind-bending age.

For example, the collision between various continental plates and what is now North America created the Green Mountains in Vermont and, much later, the White Mountains. Our mountains are more interesting than Vermont’s mountains only because the Green Mountains were created first and have been eroding longer.

Rocks – they’re not as boring as you might think.

Return to the Concord Monitor

Return to the Concord Monitor