Science is at its best when researchers poke around in interesting places just because they’re interesting, with no idea of what they’re going to find. Every now and then they produce one of those surprises, like penicillin or microwave ovens, that make the scientific method so useful, as well as so very entertaining to watch.

A case in point: Comparing the genomes of various related fungi led to the realization that we might be able to cure bats of deadly white-nose syndrome by putting them in a 1970s party room lined with rock posters, then cranking up the black lights.

Okay, the Hendrix posters are my imagination. But the UV light is real science.

“Studying the comparative genomics provided a mechanism of attacking the fungus. … It would have taken a long time to figure this out, otherwise,” said Jeffrey Foster, currently an associate professor at Northern Arizona University and previously at the University of New Hampshire, where he and grad students did work that contributed to the new finding.

Now that you’re either tantalized or baffled, let’s back up.

The fungus has long been known in Europe, but those bats survived. Researchers at a number of institutions have been trying to figure out why, to see if the answers can help North American bats.

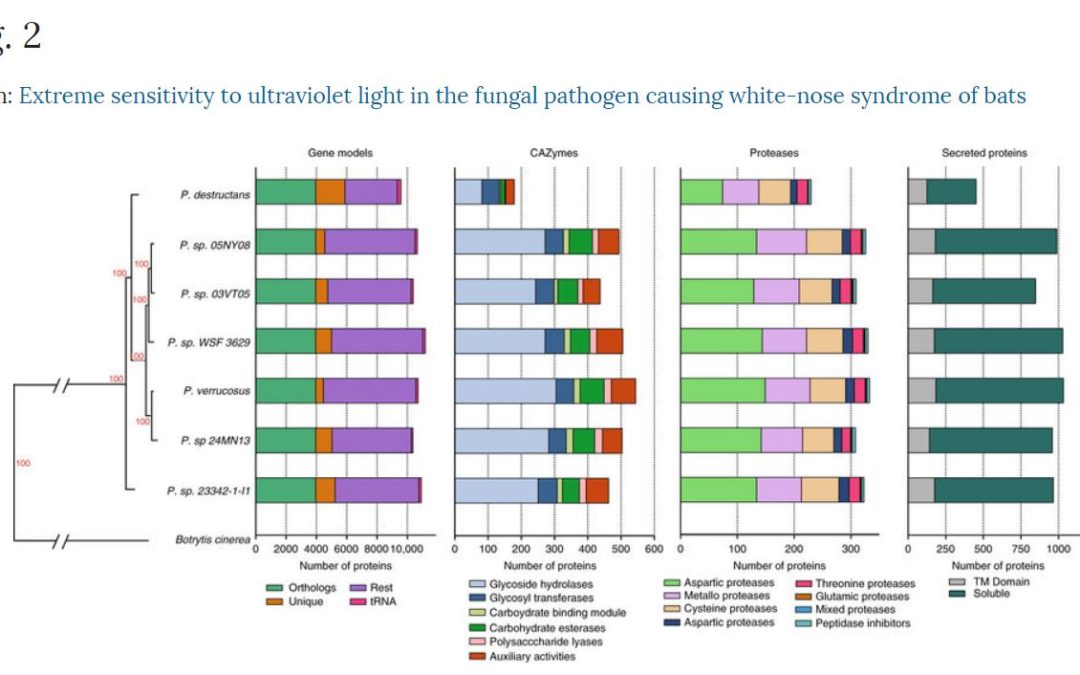

Among them are folks at the Center for Forest Mycology Research (“mycology” being the study of fungi) from the U.S. Forest Service in Madison, Wis. They reached out to Foster, who at the time was at UNH in Durham, for help analyzing the genome of PD and comparing the results to the genome of some close relatives.

“Just about anywhere you look in soil, particularly in colder climates, you’ll find relatively close relatives to PD. But PD, you’ll only find it in caves, associated with bats,” Foster said.

A key point to keep in mind is that neither they nor Foster had any idea whether this would be useful and they certainly had no particular target on the genome in mind.

“We were just trying to figure out what makes PD tick,” is how Foster put it.

“The question is whether PD is just soil-adapted fungus or is it specifically adapted to bats itself; has something changed to allow it to merge out of the soil and become co-evolved with bats?” Foster said.

Comparing the genes, as detailed in a paper in the science journal Nature Communication, produced a surprise.

“It turns out, one of those differences is that PD is susceptible to ultraviolet, unlike close relatives,” Foster said.

This was unexpected, but it makes sense, as many discoveries do after somebody else has discovered them. The ultraviolet portion of the spectrum packs more of a punch than visible light, which is why it gives us sunburn. Fungus that lives in the soil needs protection against it, but fungus that lives in caves doesn’t.

So what, you say? Well, the finding leads to the hope that shining ultraviolet light in a cave, with or without Hendrix posters, might kill off the PD without disturbing everything else.

“It suggests to us as a potential Achilles’ heel, a way to attack this fungus and not kill other things that are in the same environment,” Foster said. “That’s a big challenge; caves have cave-adapted organisms found nowhere else. It’s really important that you do not perturb those environments – you can’t, say, go in and fumigate it, or put bleach in an entire cave.”

Since there is currently no effective way to treat bats that are infected with white-nose syndrome, this is could be a very big deal, indeed. The Forest Service has received a $155,947 grant to test out the idea. Keep your fingers crossed.

And it’s all because of what is known, by a rather hoity-toity phrase, as pure science – investigation for its own sake, rather than investigation with a specific goal in mind, a.k.a. applied science.

Pure science can be, and often is, a waste of money and time, which is why it’s a favorite target of bean counters and budget cutters who know a cheap laugh when they see one. But I can think of few things that we humans can be more proud than our drive to understand the universe, life, ourselves and anything else we come across, even when there’s no obvious profit or benefit.

Makes you proud to be human, doesn’t it? And if it brings little brown bats back to my barn, all the better.

Return to the Concord Monitor

Return to the Concord Monitor