Concord has what appears to be the nation’s best-preserved gasholder, the name for a large building that once held flammable gas made from coal, which was commonly used for municipal lighting in the days before natural gas. It has just been added to the National Register of Historic Places, as I note in today’s Monitor – which is of interest to Granite Geek not because the building is handsome (which it is) but because its massive internal floating cap is still intact.

In the middle of the 19th century most cities of any size had at least one gasholder – a big, round, brick building that was usually located downtown to reduce the amount of piping that had to be built. Coal was processed to make gas (heated in the absence of oxygen) , usually on site, and then pumped into the gasholder until it was needed.

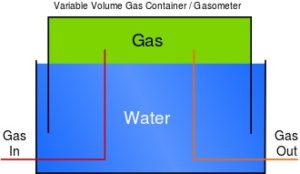

Gas was stored inside a gasholder under a floating cap. The brick building surrounded this entire arrangement.

The interesting part, to me, is the way it was stored: above a bed of water and covered by a floating cap that rose and fell as gas was pumped in or pumped out. (The illustration above is from wikipedia.)

In Concord, the cap was 88 feet in diameter and weighed several tons, a weight that maintained the proper pressure on the gas. It could rise almost 30 feet to the ceiling, held in place by wheels on vertical rails along the walls. It was connected to an arrow outside the building that showed the height of the cap, and thus the amount of gas that was stored inside the building.

While there are scores of intact gasholder buildings around the country, this appears to be the only one where the cap still exists. There’s no water or gas in the building, of course – it hasn’t been used since 1953 – but all the mechanisms are still there.

Cool, right? Yes, but owner Liberty Utilities say it could cost $500,000 just to stabilize the building so it won’t collapse like a portico did in 2016 (brick buildings from 1888 need lots of care) and as much as a million bucks to make it so that people can go inside. They don’t really want to spend that money on a property that they have no use for, so its future is uncertain.

Return to the Concord Monitor

Return to the Concord Monitor