I was once asked to describe the difference between urban and rural. Simple, I said: It’s septic systems.

If you’re connected to a wastewater treatment plant then you’re a city person, no matter how bucolic your surroundings. But if your toilet dumps into a concrete box buried in the yard then you’re rural, even if you swank around in a McMansion development.

By that definition, New Hampshire is pretty rural.

An estimated three-quarters of dwellings in New Hampshire, including my home, have septic systems. Another way to guess numbers: the state Subsurface Systems Bureau examines 5,000 applications each year for new or replacement septic systems. Assume that half the permits involve new systems and the average septic system lasts 30 years and you’ll find there are 75,000 tanks full of bacteria busily breaking down scum and sludge (scum floats, sludge sinks) to give us the luxury of indoor plumbing.

So it was very alarming to hear that, as the latest example of COVID Ruins Everything, the stay-at-home-and-clean-obsessively life is threatening this ecosystem.

“We’re seeing a 20% rise in failures,” said Robert Tardif, administrator of the Subsurface Systems Bureau. “We can’t say for certain that’s the cause, we haven’t done scientific studies, but it seems likely.”

I approached Tardif because I have only a vague idea of how a septic system works and why we’re seeing problems. He has worked for the Subsurface Systems Bureau (I love that name) since 2002 and been the administrator since 2009, so he knows whereof he speaks. Among other things, he has developed a response to those who raise an eyebrow at his career: “It may not be glamorous but what would you do without me?”

With his guidance, here’s what I learned.

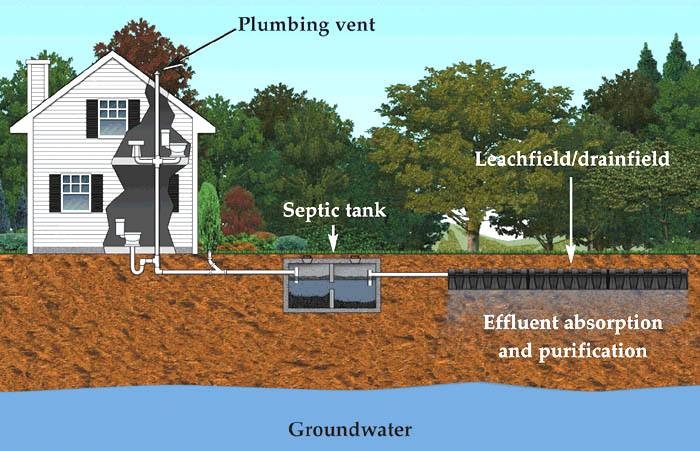

Anything I flush or wash down the sink or bath gets dumped into a 1,000-gallon tank buried outside my den window. I know where it is because the snow melts there before the rest of the yard. Wastewater is warmer than winter soil.

In the tank are bacteria that breathe air (aerobic) and bacteria that don’t t need air (non-aerobic). Both are necessary, but the aerobic bacteria are more useful because oxygen is a terrific fuel source. Both types develop naturally. A properly maintained septic system doesn’t need any bacteria-boosting additives.

The tank contents separate into three layers. Scum float on top, consisting of fats, oils, greases (known as FOG in the business, Tardif said) while sludge sinks to the bottom. In between is a “clear zone” of liquid kept clear by bacteria breaking down many of the solids so sludge won’t fill up the tank.

One key to septic design is that the outlet valve from my house is the right position and size to empty into the clear zone, not getting blocked by scum or sludge, and the outlet valve draws from the clear zone. The outlet valve lets liquids and some suspended solids to flow to underground pipes or chambers around the tank – that’s the leach field.

The other key to septic design is that the leach field has the right slope and size so waste can ooze out and percolate into the soil, where it’s further cleaned up by bacteria before making its way down to groundwater. Determining that this works is the job of the “perc test.”

(One thing that Tardif said really surprised me: Those curved vents you see sticking up from some septic fields, known as “candy canes” due to their shape, aren’t there to let gases escape. They do the opposite, allowing air to go down into the septic field and keep aerobic bacteria alive. The stinky gases from septic tanks actually move back into the house and escape via the plumbing vent.)

COVID-19 is disrupting septic systems in two ways, Tardif said. One is that more people are home all day, so wastewater is constantly arriving.

“It used to be there was a surge of water in morning and evening, taking showers and doing dishes, but overnight and during the day the leach field can rest. With everybody at home, that rest period during the day no longer happens,” Tardif said.

This can wear out the bacteria. Plus, all those flushes and showers that used to happen at work or school or the gym are now being dumped into home septic tanks, which can raise liquid beyond levels for which the tank was designed.

The other disrupter is all the cleaning we’re doing to make sure no coronavirus lurks on surfaces. Too much of these soaps, detergents and other disinfectants sent down the drain can kill the bacteria in septic tanks.

This leads to a buildup of sludge and scum, which can flow out into the leach field, killing bacteria and allowing the buildup what Tardif called “black gelatinous glop” in the soil. The glop prevents water from percolating down which means that it percolates up, bubbling up through the grass and freaking out homeowners who have to spend many thousands of dollars to replace the field and maybe the tank.

One lesson is to get your tank pumped if it’s overdue, removing buildup sludge and scum and giving it more leeway.

Another lesson is to dispose of fewer cleaning products. Unfortunately, you’re not supposed to put liquid waste into the trash, so that advice is hard to follow. The only solution seems to be to do our COVID cleaning more judiciously. We shouldn’t splash cleaners all around but apply them intelligently.

In other words, cleaning and using the bathroom is yet another thing that has gotten more complicated in our pandemic life.

On the other hand, maybe it hasn’t gotten more complicated. It just seems that way because previously we were ignoring reality.

“People flush their toilet and think it’s just gone. They think it’s magic,” said Tardif. “I can’t tell you how many times I’ve heard: ‘I didn’t even know I had a septic system’.”

Return to the Concord Monitor

Return to the Concord Monitor

Also, if your home is near a stream or lake, uphill in the watershed, you can be leaching chemicals into the waterbody you moved there to enjoy. There is no “away” on earth.

Good point, Sheila!

The interview touche briefly on another topic I didn’t get into in the column – pharmaceuticals. Even if you don’t flush old pills/medicine down the toilet, some of it passes through your system after you take the medicine and gets into the septic tank anyway, where it might disrupt the bacteria. This is an even bigger problem for municipal sewer systems, where pharmaceutical residue can build up in sludge that’s often spread as fertilizer.