Offshore wind power is to renewable energy as Babe Ruth is to 1930’s baseball – in a league by itself. (In 1927 Ruth hit more home runs by himself than were hit by 12 other teams.)

Although distributed solar will be bigger on a global scale, for the near future there’s no way to quickly build methods to generate electricity from a naturally replenishing “fuel” that comes close to the scale of gigantic wind turbines in coastal waters. And I do mean gigantic: a 10-MW turbine is being developed, which all by itself can produce 40% of the output of the entire Lempster Mountain Wind Farm, New Hampshire’s first.

The worldwide offshore wind output is 27 gigawatts and growing fast – that’s 27,000 megawatts or about 23 (note: I originally made an orders-of-magnitude error and wrote 2,300 – d’oh!) Seabrook power plants – and since wind blows much more steadily over the ocean than over mountain ridges, the total electricity produced by these behemoths rivals that of similar-sized fossil fuel plants.

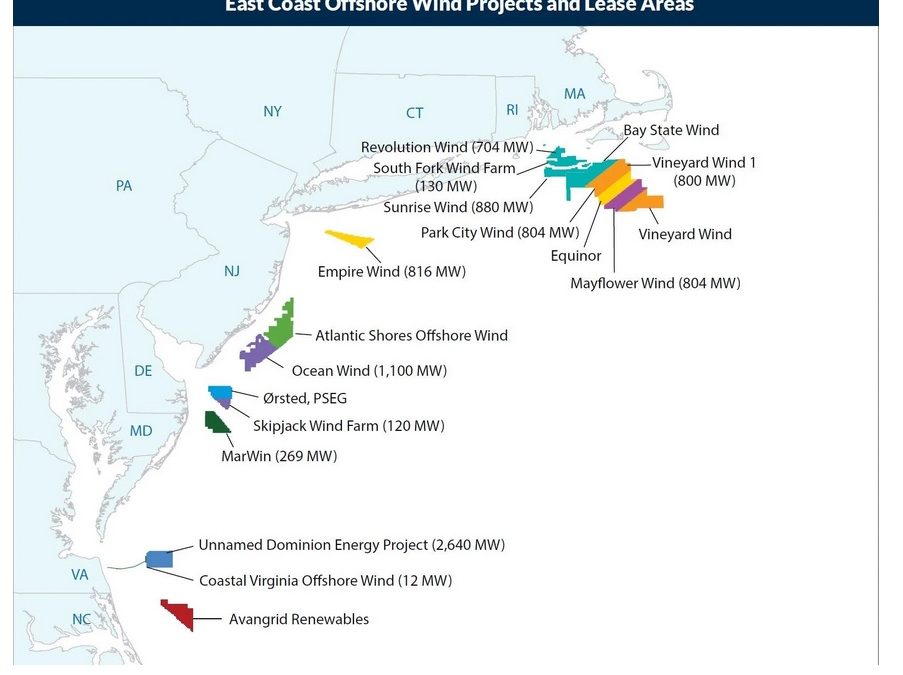

North America has virtually no offshore wind, putting us way behind compared to Europe and, increasingly, east Asia. But we’ve finally left the starting gate and there are signs it’s coming to New England and the Northeast, drawn by our wide and shallow continental shelf and our energy-consuming coastal population.

Rhode Island has the dinky (30 MW) Block Island Wind, and the southern New England states are moving toward having some real offshore wind farms within a few years via the Vineyard Wind and Mayflower Wind projects, each 800 MW. Massachusetts is trying to go further; legislators there want to develop 6,000 MW of offshore wind by 2035. New York state and Connecticut are also soliciting major wind projects, and several New England coastal cities are scrambling to become hubs for construction and servicing of wind farms.

Maine, which doesn’t have the financial muscle of our southern neighbors, is also enthusiastic and has staked out an interesting niche: Floating wind turbines, which offer far more flexibility in operations. The University of Maine has been a research leader in the field and despite a delay caused by the inexplicable opposition of the former governor – how anybody can be flatly opposed to offshore wind power is beyond me – is moving ahead. They just got $100 million in investment from Japan’s Mitsubishi Corp. and German utility RWE for a demonstration turbine; that’s serious money.

As for New Hampshire – well, we’ve just passed a law creating an offshore wind commission to make sure our laws and regulations don’t get in the way. That’s necessary but not exactly riveting. If you want to know more about how this could affect our power markets, check out an Aug. 18 webinar from Clean Energy NH.

It seems to me that New Hampshire was destined to be a laggard in this area, since we have the nation’s shortest ocean coastline and no history of offshore industrial development (despite Meldrim Thompson’s oil-refinery flirtation with Aristotle Onassis). But if we can be any part of it at all, that could be good for our pocketbook. At the very least, let’s cheer on our neighbors to add as much of this carbon-free electricity to the grid as possible, as fast as they can.

Return to the Concord Monitor

Return to the Concord Monitor

“27,000 megawatts or about 2,300 Seabrook power plants”

Per https://www.nexteraenergyresources.com/pdf/seabrook.pdf : “Westinghouse Pressurized Water Reactor with a net electrical output of 1,250 MWe”. MWe is electrical output, MWt is thermal output.” That’s at 90% capacity factor, and largely scheduled so that fuel replaced can be done in seasons of low demand.

27,000 / 1,250 = 21.6 Seabrooks. It’s actually a lot less. Land based windturbines have a capacity factor of some 35%, big offshore rigs should do better, but I don’t know what the figure is.

Ouch – off by an order of magnitude!

Two orders of magnitude!

At least my error about orders of magnitude wasn’t off by an order of magnitude.