f you are like me, you have wrestled with a lot of puzzles during these stay-at-home months.

Jigsaw puzzles, crossword puzzles, Sudokus, chess puzzles, retrograde chess puzzles (intriguing; check it out), even one those metal puzzles you try to take apart while waiting for your drink at a bar which somehow ended up in a drawer. I’ve been doing them all after a bazillion hours stuck in the house and I bet you’ve been doing the same.

But none of us have done puzzles like Eric Tentarelli did puzzles.

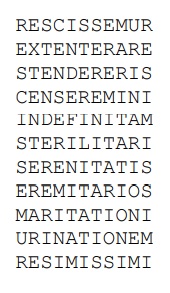

Tentarelli used a mix of computer database tech, linguistic insight and patience – lots and lots of patience – to become the first person to publish a 10×10 and a 11×11 word square, using only solid (no hyphens) words from a single language, topping the previous 9×9 record. And he did it in Latin, for reasons that will be explained later.

This isn’t merely a COVID-driven accomplishment, although the pandemic sped things up. He has been working on this for perhaps five years. Why?

“There’s the satisfaction of solving something that was an unsolved problem for more than 100 years in a way nobody had done even though all the tools were there,” he said.

“The number of combinations in a word square is very large. The possible letter combinations is greater than a googol,” Tentarelli added. “It’s not often you can work on something that fits on a sheet of paper that has combinations more than a googol.” (NOTE: Yes, I wrote “google” instead of “googol” in the first go-around. Yes, I’m an idiot.)

A word square is a crossword without any black squares to separate words. Constructing a 10×10 square requires finding 10 distinct words and stacking them so that their letters line up and spell out the same 10 words vertically.

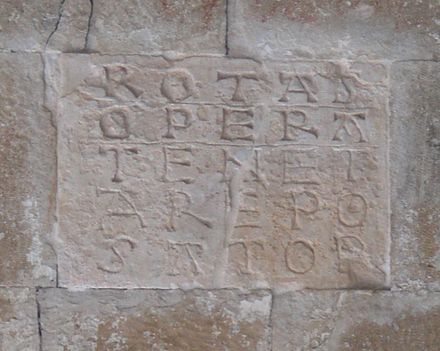

Word squares have been around for almost as long as we’ve been writing words. Small ones are found in Ancient Roman graffiti and bigger ones populate some Medieval texts.

“They were thought to have magical properties,” said Tentarelli, perhaps most famously in the five-letter Sator Square, which can be found all over the place in Europe, and in something called The Book of Abramelin the Mage. Word squares can also be approached from a more mathematical bent, as a variant of packing problems in N-dimensional space.

You can’t fiddle with word squares for very long before wondering how big they can get. Making a 3×3 word square is a snap and 4×4 isn’t too bad, but beyond that seems pretty hopeless. “You know how difficult it is to construct a crossword puzzle? Then think how much more difficult if you’re not allowed to use black squares,” Tentarelli said.

Enter the world of extreme puzzle-making.

Tentarelli, who grew up in Atkinson and works in a field he describes only as “revolving around strategy and statistics,” is part of that world. He went to MIT and got a Ph.D. in condensed matter physics, reminisces about reading Games Magazine as a kid, and has had a crossword puzzle printed in the New York Times. When he heard that people were stymied getting past a 9×9 word square, he got interested: “It’s rare to hear about a problem that was unsolved and in the field of word puzzles.”

Tentarelli said the solution required alternating between the computer approach and the human. The geeky and patience-requiring parts of the solution involved compiling lists of words from reputable dictionaries into a database, with grammar rules to create 10-letter variants when, for example, nouns are made plural or verbs are put into different tenses.

“I’ve been entering words, coding them numerically to define how they would be conjugated, then running a script that would generate the word forms,” he said.

The high-level decision was to do it in Latin rather than English, French, Klingon or Esperanto. As he explains in an article published in the latest issue of WordWays, an online journal about “word play” from Butler University, Latin is ideal because of “its extensive and overwhelmingly regular system of inflectional endings.”

English has some endings that finish up on many words, “-ING” being the most obvious example. but Latin has plenty more including some that extend to four and even five letters, which makes it easier to find word squares. “In Latin, if the words in the bottom rows combine to produce nothing but common inflectional endings, such as -NTUR or -ATIS, there is good reason to hope the remainder of the square may be filled,” he wrote.

His current word list “contains approximately 220,000 base words. … The number of resulting inflected forms, after duplicates are eliminated, is about 3,900,000. That includes words of all lengths but fortunately 10- and 11-letter words lie in the middle of the distribution (because the average word length in Latin is slightly higher than in English), so the final list currently includes about 520,000 10-letter words and 575,000 11-letter words.”

The WordWays article lists all the words that he uses in various solutions, such as: “ARANEATA is the feminine nominative singular of the perfect participle of the verb araneo, which means ‘be full of cobwebs.’”

There may be some application to all this in cryptography, Tentarelli said. But mostly it’s just for fun, which is something we’re all in need of these days.

“I’m working on the 12-square,” he said. “I need to expand the word list.”

Return to the Concord Monitor

Return to the Concord Monitor