Of all the forces that we learned about in high school physics, “friction” is the one that grips our attention in winter. Especially when it doesn’t grip anything else.

A very low coefficient of friction is bad enough when you’re on foot but can be fatal in cars. That’s why New Hampshire, like many states, tries to let drivers know when slick conditions exist as part of its road weather systems.

You’ve driven past road weather systems along highways and busier roads a zillion times but may not have noticed them: They’re mostly poles with some equipment on top to constantly monitor air temperature, humidity, wind, precipitation and temperature.

“Weather tells us what’s happening at 10,000 feet and above – radar will show that it’s snowing out but maybe it’s not getting to the ground. These tell us what really happens where we care, which is from 100 feet down,” aid Caleb Dobbins, state maintenance engineer for the Department of Transportation.

Ever since the state started rolling out its road weather systems in 2007, it has included an estimate of “grip factor.” As explained by Lee Savary, a communications technician with DOT’s Transportation Management Center, the system uses a low-power infrared beam to calculate “the actual amount of water, ice, and snow in fractions of an inch” on the pavement, then uses a proprietary algorithm to turn it into a “grip factor.”

“For the sensors that we use at NHDOT, a grip factor of .82 represents a completely dry road with full traction between the asphalt and vehicle tires. A wet road shows a reduced grip factor of .7 and a snow or ice covered road with minimal traction would show a value of .4 or under. The lower the grip factor outputted by the sensor, the lower the traction and the more slippery the roadway surface is at any given time,” he wrote.

This information is used by state police, DOT and others to warn drivers or to lower speed limits. Eventually, it may be linked automatically into roadside message boards.

This method does have limits. Each station calculates grip factor from a small patch of roadway right alongside it, which may be affected by local conditions. And I really mean local.

“We’ve had (times) when just one station has a low (grip factor). We didn’t know why. … It’s because some tractor-trailer didn’t clean off the top and all the snow blew off and landed there. Even though it’s warm, sunny, if that two-by-two (meter) area is covered by snow, it thinks the whole road is covered that way,” said Dobbins.

Grip factor isn’t part of the international system of units. New Hampshire uses road weather data from the Finnish company Vaisala that does its own proprietary calculation.

“There’s no federal mandate on how it gets measured, so each device has potentially different grip factors,” said Nicholas King, a traffic management center program manager. “If you cross a state line, it might differ. What we consider .6 they might consider .5.”

But as long as safety officials know how it correlates with road conditions, it’s still very useful.

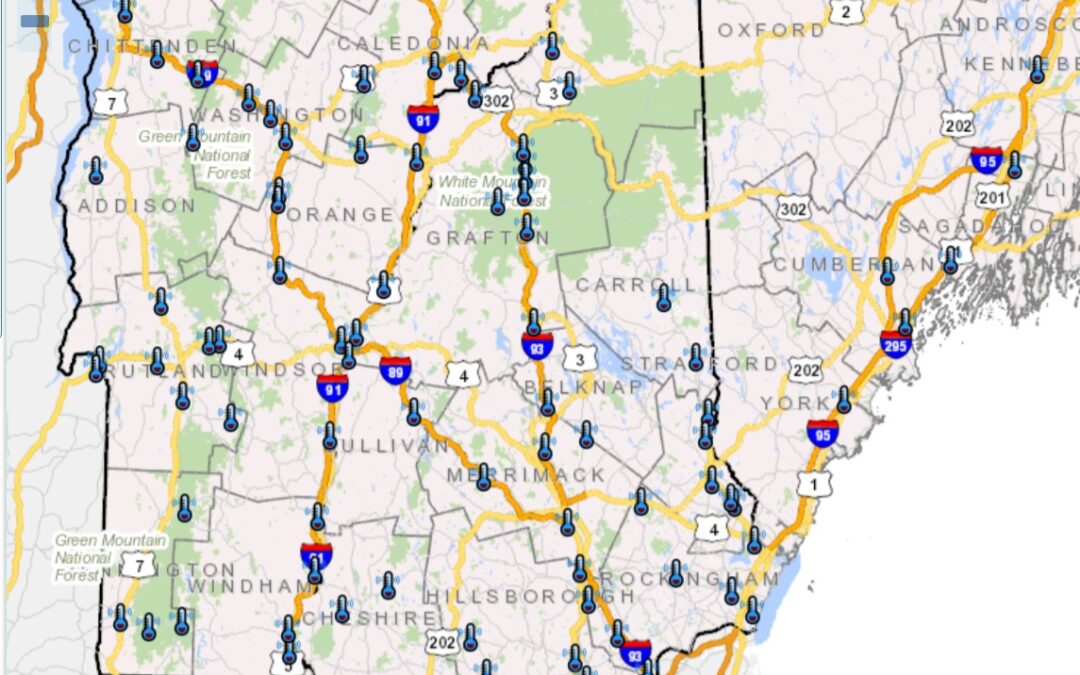

Data from the state’s 38 (if I counted correctly) road weather stystem stations as well as stations in neighboring states are live online at www.newengland511.org. It doesn’t include grip factor, presumably because of the difference between states.

One important data point is that the stations report both air temperature and surface temperature. They’re often different, especially after the sun has just risen or just set, since pavement changes temperature more slowly than air. Depending on that differential, rain can become ice when it hits the road or snow can melt and then turn into ice.

If you’re trying to keep the roads clear, however, data is important but street smarts (quite literally) are needed.

For example, Dobbins noted that if it snows when the air temperature is very low then DOT, counter-intuitively, does not want to treat the road with salt or brine.

In extreme cold snow is dry and usually blows away as cars zoom past, clearing lanes without effort. Treating that snow could melt some of it, causing ice and making things far more dangerous, he said.

“You depend on general institutional knowledge of the guy who’s going out on a daily basis,” he said. “When Channel 9 shows that it’s snowing in Vermont – they can look at stations and say, is it really reaching the ground … and what should we be doing to prepare.”

Return to the Concord Monitor

Return to the Concord Monitor

Thanks for this article! I have been very curious about those strange light poles on the roads. I imagined video cameras, or some sort of speed monitor or who knows what. Fun to know they are just measuring ice.