A month ago this column talked about the possibility of using wastewater monitoring to keep an eye on COVID-19 when – we move into endemic status.

The Centers for Disease Control has now taken a step in that direction.

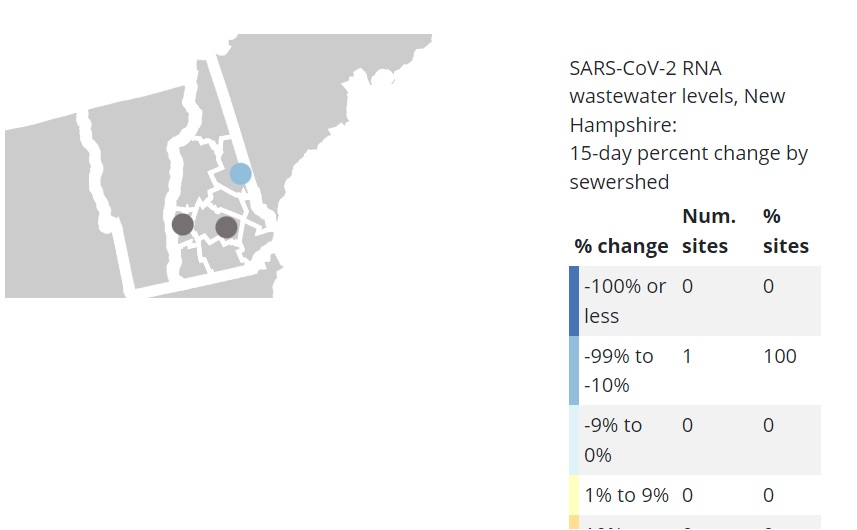

Last week it released a web dashboard (https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#wastewater-surveillance) that showed results of monitoring at hundreds of treatment plants around the country, including three in New Hampshire: Concord, Claremont and Conway. (I assume the alliteration is a coincidence and not a secret code from the Deep State.)

Dr. Benjamin Chan, state epidemiologist, mentioned the CDC dashboard in the weekly pandemic press briefing but noted “how exactly the wastewater testing is going to be used, I think, still remains to be seen.”

As it stands now, the CDC dashboard doesn’t tell New Hampshire much. The only data at the moment is from Conway, which says merely that the amount of detected genetic material related to COVID-19 fell between 10% and 99% over the previous 15 days. About three-quarters of the 260 testing sites in the country showing results have a similar status.

If you’re a nurse or doctor in the Washington Valley that’s reassuring but I’m not sure what it tells the rest of us.

Sewage monitoring is pretty straightforward. Drop a bucket down a utility hole in the street to get some of the effluent, then hunt through it for genetic material related to the SARS-CoV2 virus that has been, shall we say, released into the sewer system by people upstream.

It won’t tell you who is infected and is subject to a lot of variables (Did rainwater get into the system, diluting it? Has the population shifted due to holidays? Were there changes in plant operation?). But it gives a decent, quick and cheap overview of trends in the virus at a population level. Plus, nobody whines that their freedom is being harmed when you do it.

Keene State, UNH at Durham and Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center are among the public labs doing the analysis and a number of commercial labs are also involved. It’s still a patchwork system but it’s growing.

For New Hampshire, there’s one big problem with this approach. About half of state residents, including me, are on private septic systems so we’ll never be part of the monitoring. If we rely too much on sewage monitoring we could miss a COVID outbreak in rural areas.

The only real way to determine the spread of a disease in a population is through random, population-wide testing. A few such programs exist around the world: Britain, for example, aims to obtain swab test results at least fortnightly from around 180,000 people and blood tests monthly from around 150,000 people.

Random testing is expensive and intrusive. So is suffering from a pandemic. Guess which one is more likely to occur in the future?

For coronavirus-related information and updates throughout the week, visit concordmonitor.com/coronavirus.

Return to the Concord Monitor

Return to the Concord Monitor