To make financial sense when burning wood for a large housing development, I have recently learned, you need to do something that sounds kind of crazy: Use it to cool yourself.

“That’s the key. … District heating with wood is not a new thing, it’s the use of heat energy to power air conditioning in the summertime that makes it work,” said Charles Niebling, an energy and forestry consultant who has been around the state’s timber industry for a long time.

I was picking Niebling’s brain about two upcoming developments: New London Place, a quarter-million-square-foot senior living complex that should open in New London in 2025, and Ridgeline Community in Conway, where ground was broken in March. They hold promise for using biomass energy in large developments without destroying the environment or investors’ savings, something that forest-filled New Hampshire would like to see more of.

Both will have centralized systems that burn wood chips for a multitude of buildings – 44 one-bedroom cottages and a 106-unit assisted living facility in Ridgeline’s case, and 12 cottages plus a facility with 96 apartments and 60 assisted-living units in New London Place.

This kind of district system is old hat but these will be the first in the state to have “combined heat and power” or CHP systems, right on sight. That’s compared to biomass boilers providing only heat, as was done by the former Concord Steam, or only electricity, as is done by the state’s wood-burning power plants. Both of those systems have struggled financially, with Concord Steam shutting in 2017 after 79 years and the power plants struggling to stay open without government support.

Concord Steam’s problem was that its income fell when temperatures rose, while the power plants’ problem is that they waste a lot of the energy from burning wood, sending excess heat into the air. Doing both allows for more efficiency and more financial stability.

“Electricity is a byproduct of making heat” at these developments, Niebling said. Using electricity to do things like operate air conditioning or sell power back to the grid in warm months allows better operation, not to mention better finances. “Getting a 12-month load on the boiler, that allows you to make electricity and do so at high efficiencies,” he said.

The systems will provide a portion of the electricity used by the developments, which will still be tied to the grid.

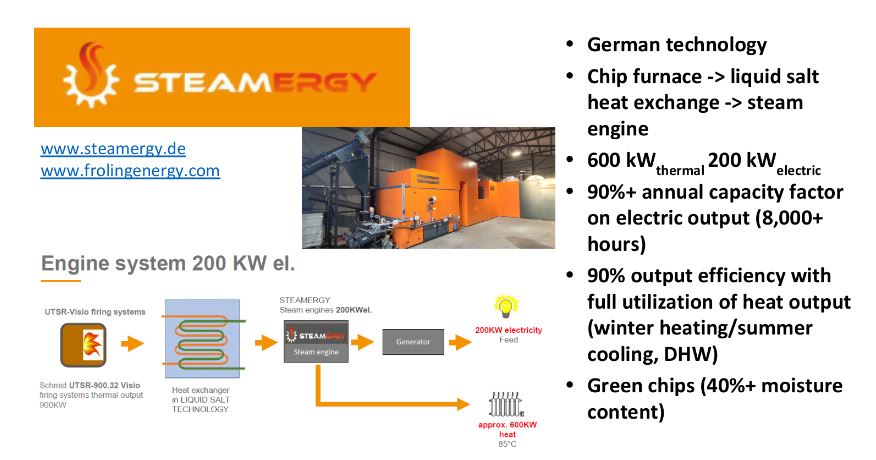

Niebling recently gave a presentation to Clean Energy New Hampshire on new and improved technologies that are making combined heat and power feasible at this scale like gassification, organic Rankin cycle and liquid salt for heat exchange.

These two housing projects are designed as demonstrations of high-efficiency CHP and have gotten significant aid to cover the high cost of new technology, including a $1 million U.S. Forest Service grant for New London Place, to support this outlet for the logging industry.

Niebling said there are many developments that could adopt a CHP district system, especially those which aren’t close to a natural gas pipeline.

It is, of course, controversial whether we should be burning wood at all in the climate emergency, no matter the technology.

Longtime readers know my opinion has gone back and forth over the years, coming down on the side of burning biomass as long as it’s done responsibly as part of forest management, and used efficiently for heat and power. Hence my interest in these projects.

Loggers shouldn’t get too excited, however. The New London project might burn 2,500 tons of wood a year and Conway around 3,500 tons, Niebling said. That sounds like a lot but it’s not.

Concord Steam burned 40,000 tons a year, the imperiled Burgess BioPower plant burns around 800,000 tons, and when the paper mill in Berlin was going full blast it consumed a staggering 2.5 million tons of wood a year. A few CHP developments are not going to save New Hampshire’s logging industry.

But they can’t hurt and if they provide energy that’s local, sustainable and that adds some variety to our overall energy picture, then I’m all for them.

Return to the Concord Monitor

Return to the Concord Monitor