One hundred and fifty years ago, something odd was taking place on Mount Moosilauke.

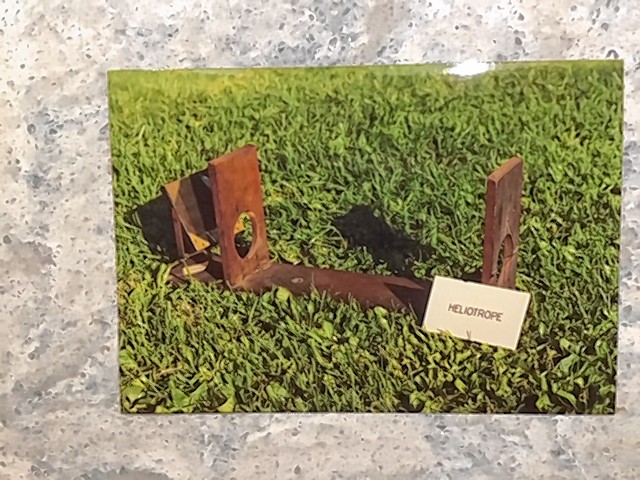

Poles 12 to 15 feet tall were being carried to the peaks and set upright, topped with a nail keg painted black and secured from “being moved by winds, cattle, or any other cause.” Then various men affiliated with Dartmouth College used funny-looking instruments to gaze in all directions and write stuff down.

If you read this column in 2018 you might know what I’m talking about. It was part of an effort by Dartmouth Professor Elihu Quimby to create the first “modern” map of New Hampshire. (That’s how I know they were all men: Dartmouth didn’t allow women as full-time students for another century.) The work on Moosilauke also took place on many other New Hampshire mountains, including Kearsarge in Warner.

The effort was an offshoot of the United States Coast & Geodetic Survey, which was accurately mapping the nation’s coastline. Quimby brought it inland via triangulation, which uses accurate measurements of the angles between three points – a triangle – to determine their exact location based on a fixed reference line. I’m sure you remember the details from geometry class.

The black kegs atop poles were built to make it easier for peaks to be seen from 50 miles or more away. Sometimes they set fires to continue into the night.

You can learn more about this fascinating project at the state’s Archives and Records Management building. That collection in Concord has more than 90,000 boxes of documents including a few dozen of Quimby’s notebooks from the multi-year project, full of penciled notations about angles and distances and locations.

Or you can get a copy of the latest volume in a very unusual self-publishing project. It’s titled “Moosilauke! After the Ice” and includes several chapters detailing efforts by Quimby and others to triangulate New Hampshire, complete with transcripts of original documents and photos.

The 400-page hardback book includes many details that were new to me even though I’vewritten about the study previously, such as the location of the baseline in Maine on which all the triangles were based.

What’s most amazing about the book, however, is that it’s part of a 13-volume set, with two volumes still to come, focusing on the 4,800-foot mountain on the western edge of the White Mountains.

Yes, that’s right: 13 complete books of history (and a bit of fiction) focused on one mid-sized mountain.

“Is there a market for this? No,” said Robert Averill, a retired physician who has been shepherding the project off and on for three decades. He is giving away the 500 copies of “After the Ice,” which he wrote with Kris Pastoriza, and says he has boxes of past volumes in his home. (Check moosilaukebooks.com to find out more.)

After talking with Averill, a Dartmouth grad who lives in Shelburne Falls, I realize that he is an extreme case of the local-history buff’s obsession with original documentation.

I belong to my town’s historical society and am familiar with the syndrome – I own scrounged copies of our town reports from the 1880s, partly from historical interest and partly because principals’ complaints about student behavior are a riot – but he has taken it to the max.

Averill started the series in the 1990s with Jack Noon, an author whose books include historical fiction based around Moosilauke. Like Topsy, for those of you know know metaphors a century ago, it has grown.

“The more I looked, the more stuff I came up with,” Averill said (every historian is nodding in sympathy). “I figured I could use all the material that I’ve been saving for years that I like.”

And there’s a lot of material about Moosilauke. You can thank its long connection with Dartmouth, which owns 4,600 acres on the mountain and operates cabins there. Literary and scientific types from the college have been generating content about Moosilauke since before the Civil War. Only Washington and Monadnock rival it for historical documentation in New Hampshire.

“I’ve taken advantage of the fact that there was some really good written stuff from the 19th century … it covered a lot of different topics,” said Averill.

“After the Ice” is volume number four in the Moosilauke reader series, which has a variety of material starting from the time the Ice Age glaciers receded. It includes chapters ranging from early automobiles to stereoviewers to Richard Cossingham, who was born into slavery and after getting freed moved to Hanover where he worked for Quimby as a cook.

Averill found out about the mapping project while gathering material at libraries. “I got more interested in what this triangulation business is about, so I made it a key theme of the book.” The 150th anniversary of the summer Quimby spent in a station on Moosilauke is a happy coincidence.

Averill has two more volumes planned and thinks that will wind up the project.

Maybe. But judging from what I know about local historians, I wouldn’t count on it.

Return to the Concord Monitor

Return to the Concord Monitor