In what I regard as a pleasant surprise, the state legislature (a body of which I am not usually fond) did a clever thing this session by making one of those easy-to-overlook changes that can improve life.

“A lot of states are looking at doing this. New Hampshire did it in the cleanest way,” said Stephen Smith, executive director of the Center for Building in North America, an advocacy group. “They really just crossed out three and replaced it with four.”

What the legislature did by passing SB 282, which Gov. Ayotte signed into law last month, was tweak the state’s building code to allow multifamily buildings up to four stories tall to have just one staircase instead of two. Previously the limit was three.

You’re probably thinking either “So what?” or “Isn’t that dangerous if there’s a fire?”

Let’s take the question of fire danger first, because that was certainly my reaction.

The idea behind requiring two sets of stairs at opposite ends of multi-story housing is that you can flee using one if the other is blocked by fire. That’s why dual stairs were baked into building codes long ago.

But Smith said improvements in fire safety have made that need outdated.

“The three-story height limit developed when we didn’t have a lot of safety features we have now, like sprinklers. This gives a little bit of credit for the safety work we’ve done,” he said.

He said that most European and other developed countries allow single-stair design for taller buildings, sometimes up to six stories, without seeing an increase in fire deaths compared to the U.S. “The rest of the world shows that you can be perfectly safe with a single stair.”

Which leads to: “So what?”

It turns out that allowing single-stair midrise buildings is one of the main wishes of new urbanism, which is a loose movement among planners and developers to create walkable, mixed-use cities with a diversity of jobs, housing and culture. The Center for Building in North America, Smith’s group, is part of that movement, which often adopts the YIMBY moniker. That stands for Yes In My Backyard, reflecting an inclination to allow more nearby development in comparison to the this-isn’t-the-right-place-for-it opponents who flock to any public hearing.

Single-stair adoptions goes along with things like ending parking minimums or loosening single-use zoning or allowing accessory dwellings (“granny flats”). The common element is that they require changes to regulations that most of us don’t see, buried in zoning or planning documents or building codes. That makes it harder to drum up public support for the changes even when the public is in favor of the final result.

In the end, the goal is to give cities and towns more options to create different types of housing, and goodness knows we need more housing.

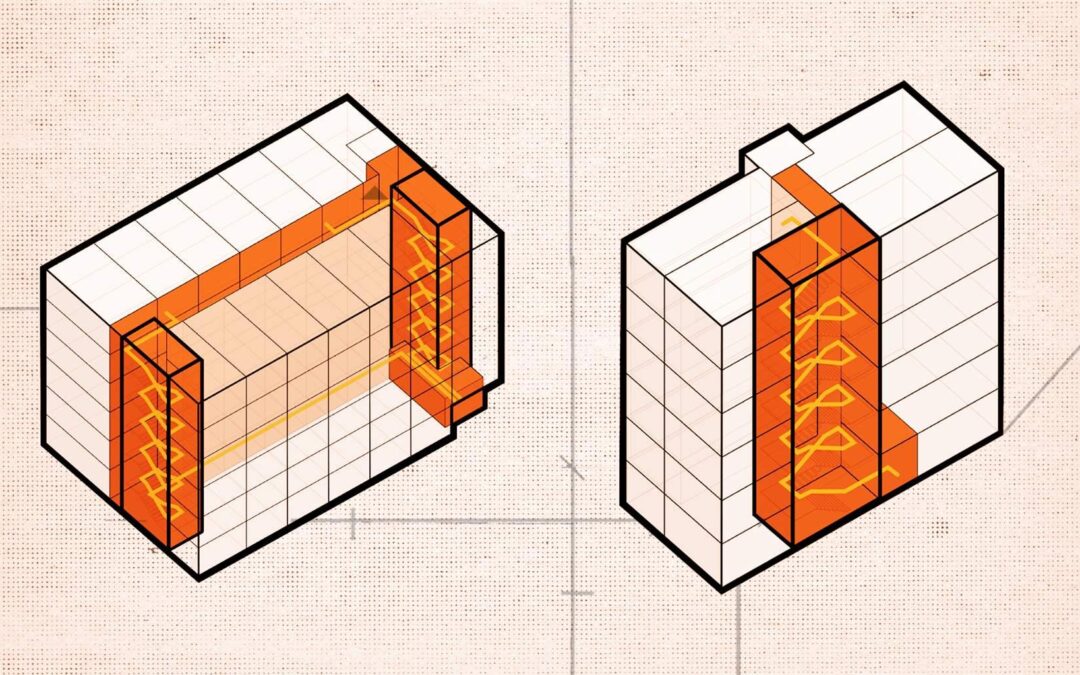

“[Single-stair] makes it possible to build smaller apartment buildings on smaller lots,” said Smith. “When you have two stairs on opposite ends of a midsize, they tend to be very large, bulky buildings that don’t fit well into fabric of neighborhoods.” Those buildings are also more expensive to build, which means rents have to be higher.

Search this topic online and you’ll find architects love single-stair codes because they allow different apartment layouts. The big benefit is ventilation from windows on opposite walls, which isn’t possible when you have apartments on either side of a central hallway connecting two sets of stairs.

Single-stair code adoption is most associated with urban areas. Smith said will be interesting to see what, if any, difference in makes in the small towns that make up most of New Hampshire.

But even if the change doesn’t lead to a sudden explosion of new apartments, it’s nice to see that government is still able to make intelligent decisions.

Return to the Concord Monitor

Return to the Concord Monitor