By Lori Wright, UNH News Service: As climate changes, Northeast winters are warming more rapidly than other times of the year. While this may mean favorable growing conditions start earlier in the year, some ecosystems, such as perennial grasslands, can take better advantage of that change than others, such as forests, according to new research from the New Hampshire Agricultural Experiment Station at the University of New Hampshire.

“By the end of the century, we expect a typical winter will be 3 to 5 °C warmer on average than what we currently experience. Although we think of winter as the dormant season for plants, it is increasingly clear that winter conditions have an important effect on ecosystems, such as forests and grasslands,” said Dr. Rebecca Sanders-DeMott, postdoctoral research associate with the Earth Systems Research Center whose research is supported by the experiment station.

“This study shows we need to pay close attention to what ecosystems are doing in winter. While we might think a longer growing season means that forests can take up more carbon, this can be offset if warm winters cause soils to thaw and lose carbon long before tree growth begins,” Sanders-DeMott said.

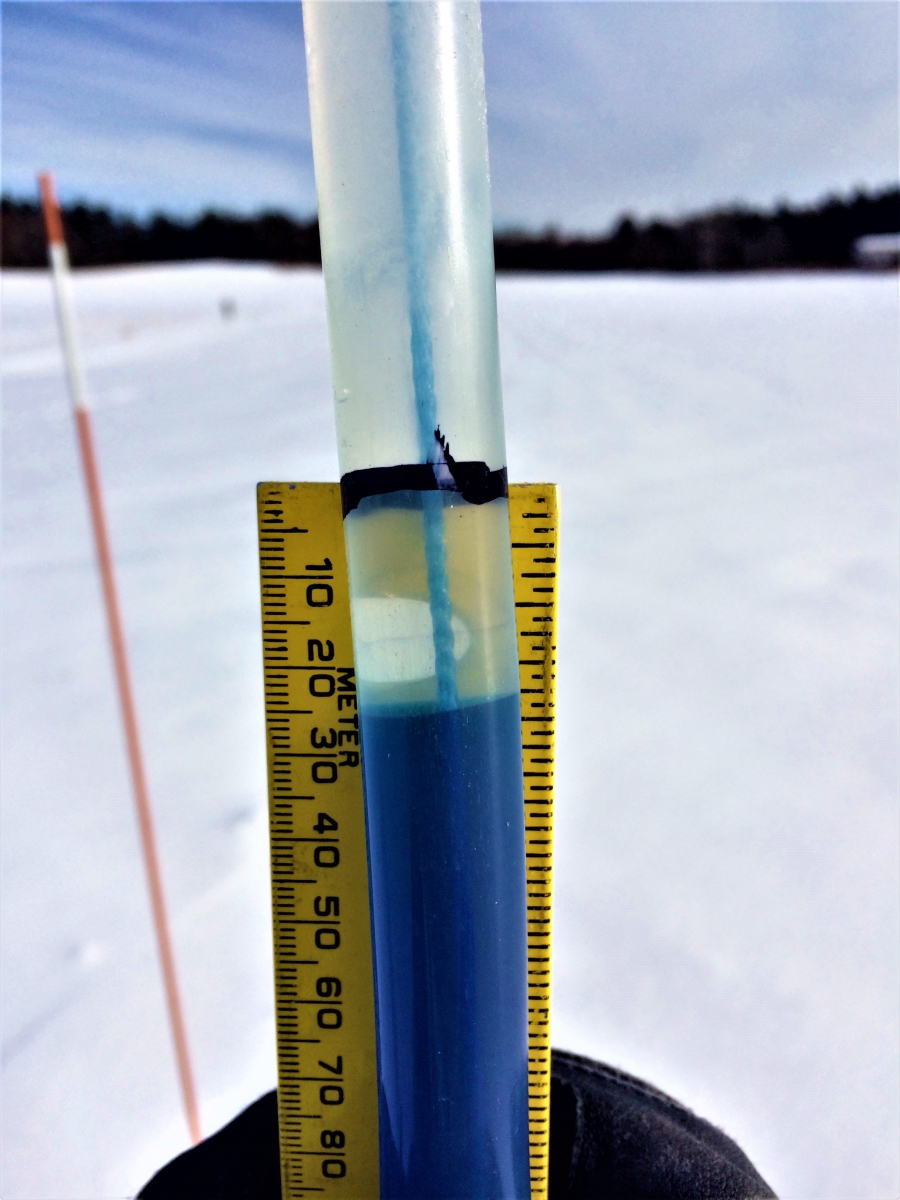

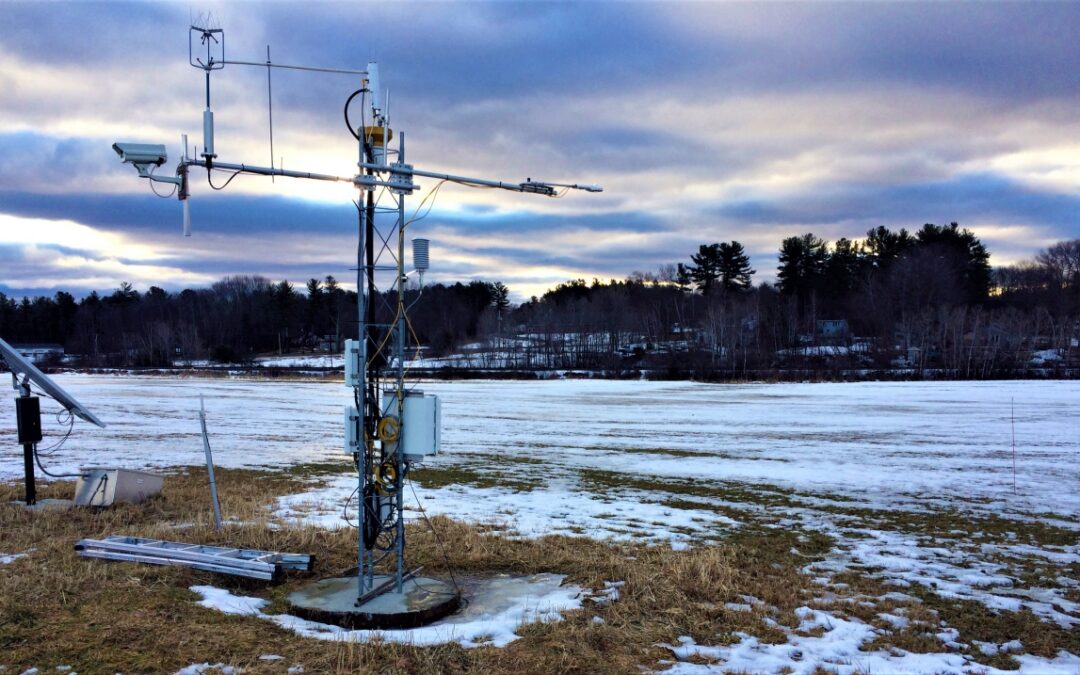

To evaluate the impact of warmer and more variable winters, researchers have been monitoring ecosystems at the experiment station’s Thompson Farm forest in Durham and Kingman Farm hayfield in Madbury since 2014. Using environmental sensors mounted high above the forest and grassland, they continuously measure how much carbon dioxide is moving into and out of the ecosystem, which is a metric of biological activity much like the ecosystem’s breath.

In the winter of 2015-16, researchers had the opportunity to observe how these ecosystems might behave in a future, warmer climate. Winter 2015-16 was the warmest ever recorded in New England but was within the range of climate projections for the end of the century.

In the grassland, record-breaking temperatures in the winter of 2015-16 caused the grasses to start growing in February, well before what is thought of as “winter’s end.” As a result, the grassland plants took up roughly three times more carbon from the atmosphere during the late-winter/early-spring than they would have during a typical year.

On the other hand, the forest could not benefit from warm winter conditions because growing new leaves takes time, and trees bear greater risks of leafing out too early if colder weather returns. So, instead of becoming a greater carbon sink, the forest lost carbon during the early spring due to elevated decomposing in the unusually warm soils. Although small carbon losses in spring are not unusual, the extended time period between soil thaw and leaf out in 2016 caused the forest to lose 2.5 times more carbon than normal.

Over the course of the full year in 2016, the forest still took up more carbon than it lost, but the net gain was reduced by about 50 percent relative to a more typical year. And while the grassland vegetation really benefited from the warm winter, it still didn’t take up as much carbon overall as the forest.

“By carefully examining the uptake and loss of carbon at each site across several winters with variable weather conditions, we are learning about how winter climate affects ecosystems that are important components of the New England landscape,” Sanders-DeMott said.

This research is presented in the journal Global Change Biology in the article “Divergent carbon cycle response of forest and grass‐dominated northern temperate ecosystems to record winter warming” (DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.14850.)

UNH research collaborators also include experiment station researcher Dr. Scott Ollinger, professor of ecosystem ecology and remote sensing, and director of the Earth Systems Research Center; Dr. Elizabeth Burakowski, research assistant professor with the Earth Systems Research Center; Dr. Alexandra Contosta, research assistant professor with the Earth Systems Research Center; Lucie Lepine, research scientist with the Earth Systems Research Center; Andrew Ouimette, research scientist with the Earth Systems Research Center; and Sean Fogarty, field research assistant.

This material is based upon work supported by the NH Agricultural Experiment Station, through joint funding of the National Institute of Food and Agriculture, U.S. Department of Agriculture, under award number 1006997, and the state of New Hampshire. Sanders-DeMott also is supported by an experiment station Postdoctoral Scientists Support Program Award. Additional funding for this project comes from NH EPSCoR/NSF Research Infrastructure Improvement Award EPS 1101245 and NASA Carbon Cycle Science NNX14AJ18G.

Return to the Concord Monitor

Return to the Concord Monitor