I like this story from UNH Today because it doesn’t oversell the project, emphasizing the ongoing nature of testing that’s needed. That seems to be lacking from a lot of tech releases these days.

By Aaron Sanborn, UNH Today:

A multi-year effort to develop and test a socially assistive robot (SAR) to assist in dementia care and help seniors age in place has expanded from the lab to homes.

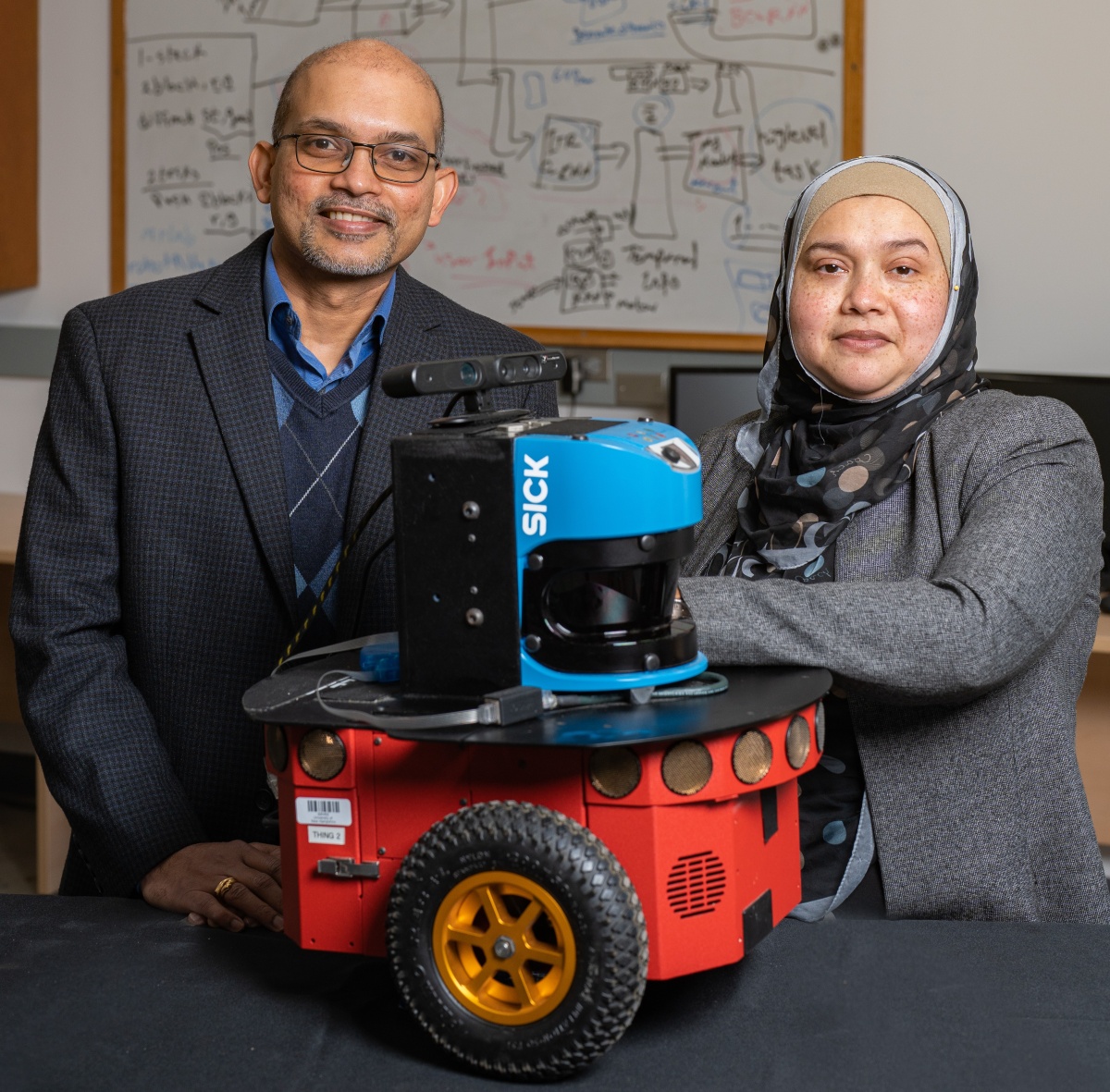

Supported by a $2.8 million grant from the National Institute on Aging, the interdisciplinary effort includes Sajay Arthanat, professor of occupational therapy; Momotaz Begum, associate professor of computer science; Jing Wang, assistant professor of nursing; and Dain LaRoche, associate dean for research at the UNH College of Health and Human Services.

“The idea is that an embodied agent, like a robot, can monitor the resident through various smart home or Internet of Things sensors and use that information to trigger different care protocols,” says Arthanat. “That might mean offering reminders, alerts, or assistance as needed. Sometimes these protocols are time-triggered, and other times they’re based on a person’s activity or location in the home. In some cases, the AI can even recognize patterns and initiate support autonomously.”

The researchers recently had the opportunity to discuss some of their progress with their academic peers at the Gerontological Society of America (GSA) annual meeting in Boston.

Current pilot work involves five families, with each study lasting about six months, long enough to observe meaningful changes in disease progression and in how the robot adapts. One pilot has been completed, and the others are ongoing.

“We’re one of the few, if not the only, projects putting fully autonomous robots into the homes of people with dementia,” Arthanat says. “There have been various efforts on this front, but they’ve mostly been in controlled lab settings or supervised settings.”

Each researcher brings complementary expertise to the project: Arthanat focuses on helping older adults use technology to enhance quality of life; Wang examines the ethical implications; LaRoche develops exercise protocols that support physical health; and Begum leads the robot’s technical development, tailoring its AI framework to individual needs.

Begum says right now the team is customizing the AI framework to adapt to each participant, but the goal is to make it more universal.

For example, in one case, the AI framework was designed to remind a participant to go for a walk with his wife when the temperature went above 65 degrees. At the same time, another household needed an alert system because the husband, recovering from a hip fracture, sometimes tries to get out of bed at night, triggering a fall risk.

Other functions include medication reminders, safety alerts, step-by-step assistance with appliance usage, and exercise routines. The robot can navigate varied home layouts, connect with door and motion sensors, and use advanced computer vision algorithms for recognizing the care recipients and the activities in the homes, according to Begum.

Wang says the pilots are a rare opportunity to observe ethical challenges in a real-life setting, such as balancing safety and privacy and fostering trust in a robot while respecting a person’s sense of independence.

with an old prototype in 2022.

For example, a study participant initially expressed interest in a daily reminder to wear the appropriate shoes when going for a walk but later found it too intrusive.

“That kind of reminder was starting to affect his sense of independence,” says Wang. “He felt, ‘I already know I’m able to do this. I don’t need to be reminded.’ What I’m seeing in this project is the real application of person-centered care — how we make shared decisions with participants about whether to use the robot, how to use it, and what it should do to truly support them.”

The team is also exploring alternatives to cameras, such as wearable devices, for families uncomfortable with in-home video monitoring.

The pilot studies are expected to conclude early next year. Afterward, the researchers plan to launch a larger randomized controlled trial with a standardized set of protocols.

Begum says she’s encouraged by the early outcomes but notes there’s still a lot of work to do, including building out technical and customer support.

“We now have a functioning prototype that can operate autonomously in real homes. That’s a massive achievement,” Begum says. “But it’s still a research prototype maintained by graduate students, not a consumer-ready product.”

Ultimately, the team believes a successful project will have a significant impact on the quality of life for elderly residents with dementia and their caregivers.

LaRoche says that during the pilot studies, interviews and focus groups, caregivers consistently cited the high costs and emotional strain of round-the-clock care — expenses that average nearly $6,000 a month for in-home help and more than $100,000 a year for long-term care.

LaRoche adds that the project also addresses a growing care provider gap, with demand for in-home caregivers currently exceeding the number of available providers.

Return to the Concord Monitor

Return to the Concord Monitor

Commercialization will come too late for my father but hopefully in time for me and my spouse. Aging in place is everyone’s goal but it’s difficult with dispersed families and high costs for hired help. Fingers crossed this really happens.