A proposal to build the state’s largest solar farm on a bend of the river in Concord has been rejected after running afoul of city zoning laws designed to keep land from getting over-covered by structures.

The ZBA on Wednesday rejected a proposal for a 54-acre solar farm off West Portsmouth Street because it had too much “impervious surface,” meaning area that would cause rain to run off rather than soak in.

“We are going by the definitions that are in the zoning ordinance for buildings, structures and lot coverage,” said Craig Walker, the city’s code administrator, who did the calculations on the project that contributed to the ZBA rejection.

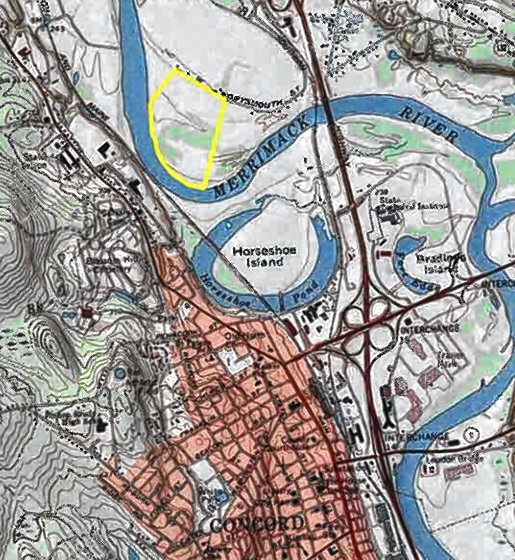

The proposed 10-megawatt solar farm would have been off West Portsmouth Street on the east side of the Merrimack River near the Exit 16 interchange of I-93. It would have been the biggest in the state by far, although a couple of larger projects are in the works.

The owner was NextEra Energy, which calls itself the world’s largest utility. It owns scores of solar projects around the country as well as many other types of energy resources, including Seabrook Station nuclear power plant.

“We appreciate the decision that the board had to make. This doesn’t fit neatly or conform to existing zoning codes,” he said. “Every kind of energy has its own needs and demands, and solar requires a lot of contiguous land.”

Walker said that under current Concord zoning definitions and rules, the impervious area of each panel is calculated by laying it perfectly flat. Under that definition the solar farm would have almost three times the amount of land coverage allowed in the zoning.

The company proposing the farm had argued that only the pillars and footings holding up the panels should be calculated, since the solar panels would be held several feet above the ground and there is room for water and light to get to the ground between them. This did not convince the board, which voted 4-1 to deny a necessary variance.

The project was also opposed by several abutters and near neighbors, who argued that it would overly change the nature of the area.

Zoning regulates the percentage of a given lot that can be impervious for a variety of reasons, including to control flooding and to improve underground aquifers, as well as to prevent overcrowding of buildings.

The area in question is residential open-space zoning, which usually allows only one structure per lot, although exemptions are allowed for things like golf courses. This type of zoning allows a maximum 10 percent of the area to be impervious; when laid flat, the solar panels would have covered almos three times as much, although the footings alone would not.

At the ZBA hearing, attorney Jeremy Eggleton, representing the West Portsmouth Street Solar LLC subsidiary of NextEra, said it didn’t appear that any lot in the city would meet the 10 percent limit if it held a solar farm of any commercial size, and notes that state law (RSA 672:1.3a) requires that renewable energy project not be “unreasonably limited by use of municipal zoning powers or by the unreasonable interpretation of such powers.”

Calculating impervious surface is often a stumbling block to solar farms. A 2015 guide put out by the state urged municipalities to “consider creating exemptions or increasing flexibility for residential solar energy systems with respect to height, setback, lot coverage and impervious surface limitations” because “in some cases, zoning regulations restrict the location of a solar PV (photovoltaic, or electricity-producing) system and prevent it from being located in a way that would be most efficient or even prevent a PV system from being installed altogether.”

Concord is in the process of overhauling its zoning code, and new considerations for solar panels and solar farms may be part of that work.

Clay Mitchell, a lecturer in natural resources at UNH, said he is developing a model ordinance about this issue that towns could consider adopting, although he said that it’s not always clear exactly how to calculate the effect on land of rows of solar panels.

“There’s very little in academic literature how to calculate this,” he said.

“The traditional way of considering (impervious surface) is usually one large, unbroken mass – a parking lot, a building. A solar array is a completely different type of construction. It’s broken up, and there’s so much impervsious surface and ground cover in between the panels that it really attenuates it,” Mitchell said.

The state Alteration of Terrain Bureau is also looking at the issue, he said.

Return to the Concord Monitor

Return to the Concord Monitor