For the first time since John Adams was president, more people live in New Hampshire than in Maine.

But that doesn’t mean New Hampshire has shed its recent slow-growth history. It’s just that Maine has started to shrink.

“The big thing is that more people are dying in Maine than being born. It’s the third straight year of natural decrease,” said Ken Johnson, senior demographer at UNH’s Carsey School of Public Policy, who has studied population trends for decades.

“Natural decrease is very unusual in the U.S. at the state level. It’s fairly widespread at the county level, but to have a whole state is very, very unusual,” Johnson said.

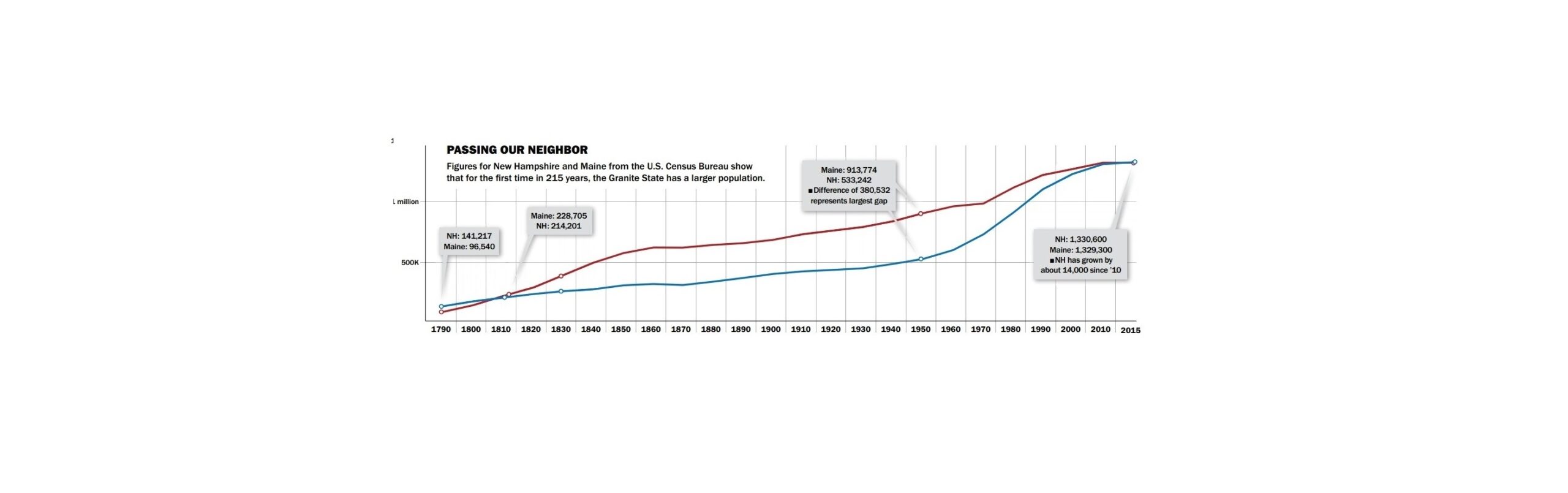

The most recent population estimates from the U.S. Census Bureau say that 1,330,600 lived in the Granite State on July 1, 2015, compared with 1,329,300 in the Pine Tree State. The last time New Hampshire’s population exceeded Maine’s was in the 1800 census, when New Hampshire as a whole had fewer people than Hillsborough County does today.

The Census Bureau estimates that Maine’s population shrank by about 1,000 people from 2014 to 2015, while New Hampshire’s population grew by about 2,600. That relative difference is likely to continue, as there is no indication that our much larger neighbor will change its demographic trend any time soon.

Johnson cautioned that the 2015 figures are just estimates based on information such as tax records, birth and death certificates and Medicare enrollment. The estimates have a sizable margin of error, so the population difference is far from certain.

“This is a crossing point, but it may have actually happened a year ago, two years ago, or next year,” Johnson said.

Still, the crossover has been coming for many years. Maine mostly increased its spread over New Hampshire for more than a century, even during blips like the 1870 census when population declined for both states as part of migration west after the Civil War.

But New Hampshire began closing the gap in 1950, when Maine had almost 60 percent more people than New Hampshire. The post-World War II surge of baby boomers and suburbia was felt much more strongly in New Hampshire, particularly in southern parts of the state, than in Maine.

A portion of population change is caused by in-migration and out-migration but what’s significant here, Johnson said, are births and deaths.

Looking at five-year trends, New Hampshire had roughly 9,500 more births than deaths between 2010 and 2015, while Maine had the opposite: 1,600 more people died than were born.

Both states are old by national standards, with a median age of about 40 years, which is 10 percent higher than the national average.

But Johnson said New Hampshire is older because it has a large population of Baby Boomers in their 50s and early 60s, whereas Maine is old because it has more retirees.

About 18 percent of people in Maine are over the age of 65, one of the highest such rates in the country. The figure in New Hampshire is about 16 percent.

Vermont, which has half as many people as New Hampshire, is in the same boat: Its total population is virtually unchanged since 2010, and 17 percent of its residents are over 65. In all three states, at least 94 percent of the population is non-Hispanic white.

Massachusetts, on the other hand, has been the fastest-growing state in the Northeast, increasing in population by almost 4 percent since the 2010 census, and only about 84 percent of its population is non-Hispanic white.

That reflects a major reason why New Hampshire is growing faster than Maine, said Johnson.

“People talk about the New Hampshire advantage. As far I’m concerned, the New Hampshire advantage is it shares a border with Massachusetts,” he said.

Return to the Concord Monitor

Return to the Concord Monitor