You’ve heard, of course, about the Internet of Things plenty of times in this column. Maybe it’s time for a different IoT: the Internet of Tomatoes.

“About 88 percent of farms around the U.S. are small and medium size, and of those, nearly 100 percent have no instrumentation,” said Erick Olsen, whose title is smart agriculture manager for Analog Devices, a Massachusetts-based data conversion and signal processing giant that is targeted toward farmers. “What we’re trying to do is not break the system, but show that by proper measurement, a new way to look at a crop and judge its quality … farms can benefit.”

Analog Devices is testing wireless in-field sensors in Peterborough, one of 19 sites in New Hampshire, Massachusetts and Rhode Island, with the goal of growing better-tasting tomatoes and other fruits or vegetables.

Tomatoes are an obvious first target, since modern agriculture has ruined their flavor in the name of storage and transportation. Even the tomatoes I grow myself, which aren’t doing too well, beat those billiard balls they sell in supermarkets.

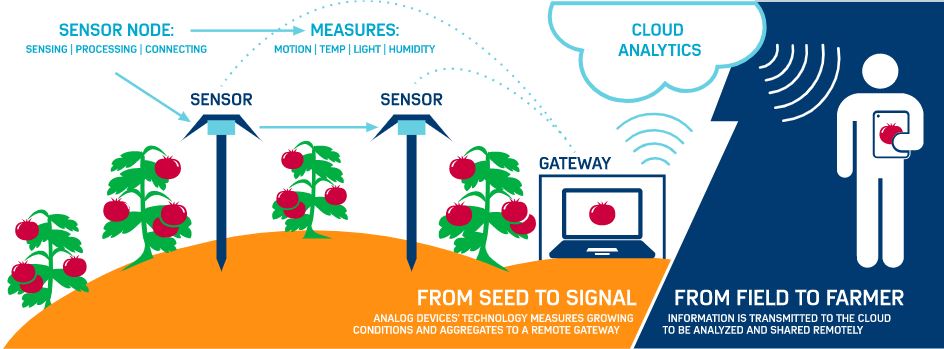

The system Analog Devices has installed at the Cornucopia Project is a prototype, or “minimum viable product” in R&D-speak. It includes sensors that can be placed throughout a field, inside greenhouses or under high-hoops systems, and which measure the air temperature and humidity and the ambient light – crop-independent information of value no matter what you’re growing.

It’s true that farmers have long collected some environmental data, at the very least from rain gauges as part of irrigation planning. Analog Devices thinks it can convince farmers to kick this up a notch, placing between one and five monitors per acre to watch for variations in conditions that can occur even on a small property and have a big effect on crop yields.

“They can keep track of growing-degree days, heat stress, things like that at a microclimate level, where most farmers don’t have any instrumentation,” Olsen said.

To folks in manufacturing, shipping or logistics, the idea of sprinkling sensors throughout the work area to keep on eye on individual products is old hat. They know that gathering the right data and acting on it properly can cut costs and increase productivity, as well as handle ever-more-complicated systems.

So it makes sense to apply this idea to agriculture, which can be thought of as a type of organic manufacturing.

The Peterborough project is installed with Farm to Fork, an educational component of the Cornucopia Project, where high-school fellows learn the intricacies of running a farm.

Very large-scale farms in the Midwest and other areas are starting to adopt the idea, but Analog Devices is targeting the sort of farms that fill New Hampshire, covering a few hundred acres at most. These places have smaller budgets to buy fancy new equipment, but on the plus side from a market point of view they really specialize – Olsen said one customer, Verrill Farm of Concord, Mass., grows 55 different varieties of tomatoes – which means they could benefit from more fine-grained data than a place that grows soybeans from horizon to horizon.

Analog Devices is also working on turning a handheld near-infrared spectroscopy tool, licensed from a company called Consumer Physics, into a specialized tomato-quality analyst. The idea is that a farmer or field hand could place the sensor alongside a tomato or any fruit with a skin thinner than, say, watermelons or pumpkins, and shoot it with light that has a wavelength around 400 nanometers.

The device would determine which types of molecules get energized inside the fruit, which sounds like an exercise from a physics lab. What it actually can reveal is the sugar and salt content and acidity level of the fruit without breaking the skin, helping move harvesting decisions from the purely qualitative, based on look and feel, to the quantitative, based on data.

“The path we’re taking is to take all this data, which farmers are too busy to look at it, (and) simplify it a bit with base levels of parameters to guide decisions,” he said, pointing to a theoretical example: “The last three days of environmental data combined with the forecast, compare to baseline … should you get the hay in?”

With data comes questions about privacy, of course.

Olsen said the farmers, not Analog Devices, will own any data collected by the equipment, and can share it if they wish.

Analog Devices plans to collect, anonymize and pool customer data and sell them for agricultural planning or research purposes, and maybe even sell them to seed and fertilizer companies who want to know what changes are coming to New Hampshire’s environment that might alter future sales. Analog Devices is joined in plans to develop farm-data management tools by a San Francisco company called Ripe.io, which is working to use its data analytics and processing expertise to create “the blockchain of food,” a distributed trust system for all things agricultural.

It that seems pretty geekish for down-in-the-dirt farmers – you can’t get much geekier than blockchain, the bitcoin backbone that shows signs of upending business processes in a host of industries – but Olsen thinks the benefits will outweigh any doubts.

“I gave a presentation at a conference … and at the start the audience was laid back, their arms crossed, legs crossed, a scowl on their faces: ‘What do you mean you’re going to instrument my farm?’ ” he recalled. “Before I was done they were leaning forward, asking questions, interrupting me.”

Return to the Concord Monitor

Return to the Concord Monitor