As Maine continues a legal struggle over the same issue, New Hampshire legislators will soon be discussing the possibility of reinventing the voting system with ranked-choice ballots.

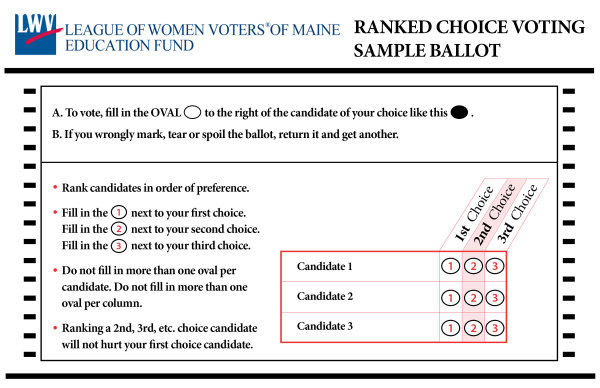

The proposal, House Bill 1540, would allow voters in a race with more than two candidates seeking a single office, such as in party primaries, to rank the candidates in order of preference rather than just choosing the one they want to win. The winner would emerge from a repeated calculation of all voters’ rankings.

The prime sponsor of the bill, Ellen Read, D-Newmarket, noted that variations of this voting method are used in some cities around the country, including Cambridge, Mass., as well as in a number of professional organizations and even in a few national elections, notably for the Australian parliament.

“It more effectively and accurately reflects the will of the voter,” she said. “It gives more choice.”

Further, Read argued, ranked-choice voting “negates the spoiler effect” in which people cast ballots to harm one candidate rather than to support one.

Her bill, which has co-sponsors from both major parties, would install ranked-choice voting for all federal and state offices, including state representative, as well as for party primaries. It would not affect local elections.

The idea of alternative voting systems with names like instant-runoff and preferential balloting has been floated before in New Hampshire, with no success. The idea is particularly attractive to independents and small-party candidates, who see it as a way to loosen the hold that the two major parties have on the political system.

Maine became the first state in the nation to embrace ranked-choice voting last November, when 52 percent of voters approved a referendum that would institute it for certain statewide races. That program is on hold, however, because the state Supreme Court said it violates a provision of the state constitution that allows elections to be decided by a plurality, not necessarily a majority, of votes. Maine lawmakers tried to pass a bill killing the idea, but it was tabled, leaving the program in something of a legal limbo.

Under Read’s bill, voters would rank all the candidates on a ballot by preference. If no candidate receives a majority of first-place votes, then the worst-ranked candidate is dropped and the calculation is redone. If once again no candidate receives a majority of first-place votes, then the process is repeated, as many times as necessary until a majority winner is found.

“The main drawback is that it’s slightly more complex than the system we have,” Read said. “It’s important to start the conversation on it, to get people thinking about the benefit and harm of different systems. New Hampshire would have to become educated and realize what they’re getting into before we do it.”

Read, who founded a group called New Hampshire Independent Voters Association, said ranked-choice voting can weaken the hold of the two parties.

“It allows us to choose people who most closely reflect our beliefs, who genuinely think of what is right, rather than what their party says,” she said.

One complexity in New Hampshire state representative races is that many seats have multiple members. The bill would handle this by giving equal weight to a ballot’s top choices equal to the number of seats that are open. For example, in a ballot for a race with three seats open, the No.1, No. 2 and No. 3 choice would all be counted as a top choice when doing the calculations.

Read acknowledged that many different systems exist and that none of them solve all the problems inherent in reflecting the opinion of the population as a whole, something that has been proved mathematically through what is known as Arrow’s Theorem.

But she said our current method, sometimes called “first past the post,” can be improved.

“There’s no perfect system,’ she said. “We’re trying to make it better; that’s the whole point of it.”

Return to the Concord Monitor

Return to the Concord Monitor