Here’s some good news for New Hampshire fishers: In the past three years it has gotten easier for trappers to kill them.

Wait, that’s not very scientific. Let me try again.

Here’s some good news for New Hampshire fishers: In the past three years, capture-per-unit effort has increased.

Much better.

Either way, it may not sound like good news if you’re a fisher fan – and who isn’t a fan of this fierce and secretive super-weasel? But the fact that it has gotten slightly easier for New Hampshire trappers to catch fishers in the past three years is, indeed, good news, because it indicates the population is stabilizing or even growing after more than a decade of decline.

Hooray! But also: Really? The only way we can estimate population size is by killing a little bit of it?

Moral qualms aside, extrapolating demographics from the success rate of an activity that waxes and wanes for unrelated reasons – trapping efforts can change due to everything from gas prices to weather to the market value of different furs – seems an imprecise and backward way to keep track of one of our favorite animals.

Such, it seems, are the complexities of wildlife biology.

Patrick Tate, a New Hampshire Fish & Game biologist and New Hampshire’s go-to guy for all things fisher, is well aware of these complexities. When I called him last week to find out how fishers are faring, he said nobody has any precise idea how many fishers live in the state.

“As a wildlife biologist, I would like to know what the number is. But it’s a very large task to get the information, and a very high cost,” he said.

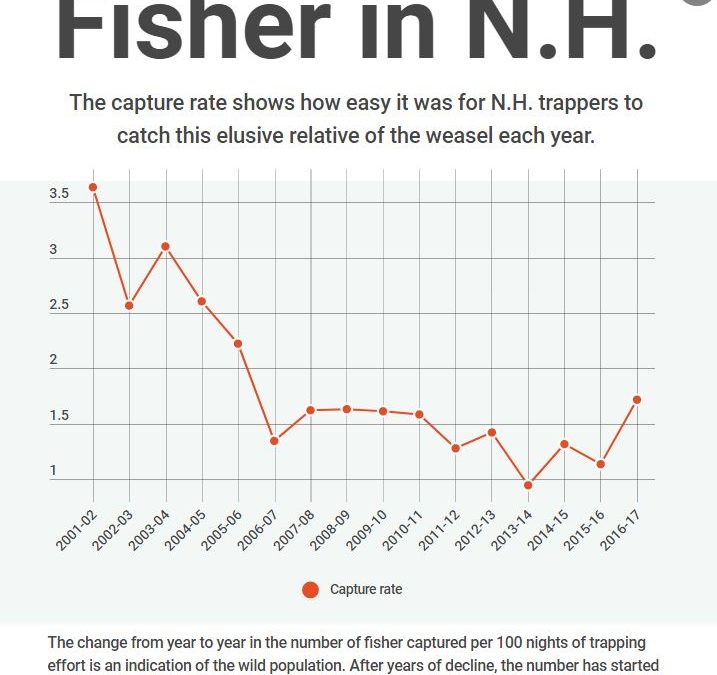

“What we use to determine abundance of fisher on the landscape is our trapping index,” he said.

Basically, they add up all the hours during fisher trapping season that the traps were out as reported by the state’s licensed trappers – who number between 450 and 550 in any given year – and divide that by the number of fishers actually caught. If the number goes up, it was easier to catch fishers, and that’s a sign that the population is increasing.

Increasing from what to what, nobody knows. But if it is increasing, presumably we can breathe easy for a while.

Why not go out and actually count fishers? Because it’s really expensive and time-consuming, and might not work very well.

The only “furbearer” animal for which New Hampshire has an official population estimate is the bobcat. If you followed the frenzied debate over a potential hunting season on bobcats in New Hampshire, you’ll know how that went.

Basically, bobcat biologists and researchers spent up to $300,000 and a couple of years examining tracks, gathering pictures from wildlife cameras, doing necropsies on dead animals, calculating fecundity from placental scars on females, determining viable ranges for this predator, and doing lots of other field and lab work. They put it all together and estimated that around 1,400 bobcats live in the state.

But in the argument over whether to start hunting and trapping bobcats, this figure grew to be questioned by many people, including one of the researchers involved. In the end, this estimate, if not exactly useless, didn’t seem worth the trouble and cost, and nobody’s planning to do it for the fisher.

So we’ll have to continue to rely on indirect indicators, like capture per unit effort, to estimate how wild populations are doing.

One result of this, incidentally, is that many (but not all) wildlife biologists support the idea of hunting and trapping. They need it as a data-gathering tool.

Just look at how state biologists descend on check stations when firearm season opens for white-tailed deer, weighing and measuring what hunters bring in. The information helps create a snapshot of the herd’s health so we can, among other things, decide whether to alter next year’s hunting seasons.

It’s not a perfect science, and you’ll find plenty of hunters and trappers in any state who think that regulators have messed up in one way or another. You’ll also find plenty of people who think that killing animals is a lousy way to study them and help them.

But for fishers, it’s pretty much all we’ve got.

“It’s a good indicator if the population is increasing, decreasing or holding steady,” Tate said.

It doesn’t say why the population has gone down and up, however. This is where more data would be helpful.

For example, Tate notes that a couple of necropsies of fisher have found canine distemper, a disease to which the species is prone. Perhaps that is an underlying cause of a decline in catch rates, but it would take a lot more study to find out.

Then there’s the question of the fisher prey-versus-predator interaction with bobcats, which are three or four times as big and just as hungry, but perhaps not quite so fixated as hunters.

“Bobcats will take the smaller fisher – usually females … but an adult fisher will take baby bobcats,” Tate said. “It’s basically a war of numbers; we don’t know the rate of predation on each other.”

Another question involves pine martens, a smaller relative of the fisher that competes with them to some extent for prey. Pine marten numbers seem to have been growing in the state – is that hurting fishers? Maybe.

Or maybe we’re just seeing nature in action. A look at trapping success rates over many years, Tate said, hints at a regular pattern.

“Fifteen years ago our population was very high, but 15 years before that, the population was low. So there’s evidence out there that would show fisher naturally fluctuate,” he said. Perhaps 2014 was a natural low point in the sine wave and numbers are rising only because that’s how the ecosystem works.

It would take a lot of work to know for sure, and we’ll probably never be willing to pay for that work, so we may never really know.

“It definitely makes it fun – and difficult,” Tate said. “That’s the art of wildlife management.”

Return to the Concord Monitor

Return to the Concord Monitor