This is a story about a Manchester startup using blockchain and peer-to-peer storage and micropayments as the basis of a fledgling YouTube competitor, which is very cool.

But it’s also a story about a small startup (21 people, one round of funding) that already has to think about the internet’s biggest unsolved problem: the horrifying ways we humans misuse social media to spread lies and hatred. Which is not cool at all.

“It certainly loses some of the playfulness that can come with” creating a tech-based startup, said Jeremy Kauffman, co-founder of Lbry.

I first wrote about Lbry – pronounced “library” but spelled without vowels partly to emphasize that it’s a protocol, like HTTP – in late 2015, when it was just starting out.

I was fascinated that it used blockchain, which I had barely heard about at the time, to let people update and share files, including videos, and possibly make some money for doing it. Plus, the use of peer-to-peer storage of files rather than storage on some central building full of servers means it bypasses the control of any corporation.

When Kauffman reached out recently to do an update, as the company was celebrating having a couple hundred thousand users, reaching funding goals and snagging some big media attention, my pushback was a lot less fun: Maybe it’s not a good idea to make it easy for people to share videos, no matter how cool the technology.

This gloomy question arose, of course, from the realization that people and groups have used the ease of sharing material via social-media giants to help societies around the world tear themselves apart. Well-directed lies online, it seems, can lead to riots, promote ethnic cleansing and make democracy a lot less stable than it seemed; is it really worth it?

Kauffman agreed there’s a concern, even if it hasn’t affected him yet: “People aren’t trying to spread disinformation with Lbry because it’s too niche, but it’s certainly something that we will face.”

He talked about some technical solutions that the firm is considering. But in the end, he doubled down on a point of view that once seemed so obvious it hardly needed to be stated: Good information drives out bad, so it behooves us to make it as easy as possible for anybody to disseminate just about anything that isn’t illegal.

“Generally, access to more information prevents disinformation from spreading, rather than preventing the spread of information in the first place,” Kauffman said.

Not long ago I would have agreed wholeheartedly – not surprising from a newspaper reporter. But watching organized groups use file-sharing via Facebook, YouTube, Twitter, et al. to whip up hatred around the world has given me pause.

Wrong, says Kauffman.

“It’s not like we are getting away from a world where all of us were always telling the truth,” he said, pointing to a couple of famous American examples from pre-internet days: the misleading (at best) way the Gulf of Tonkin affair was used to justify the Vietnam War, and the yellow-journalism-fueled push that created the Spanish-American War.

The fact that any wacko or hate-group-in-disguise can spread almost any message online means things are different than in those days, but that doesn’t mean it’s worse.

“This might result in negative things, but I think it still results in fewer negative things than trying to control information,” he said.

I certainly hope so.

In the meantime, Lbry is concentrating on growth out of their Elm Street headquarters. In December, Kauffman said, they raised almost $6 million via their blockchain, which he said will be enough money for about 30 more months.

The financial essence behind Lbry is that via blockchain it runs a continuous auction for URLs that point to your file. When I finally finish filming The GraniteGeek Movie (99.44 percent pure on Rotten Tomatoes) and upload it, I can pay to have “lbry://granitegeek” as the domain name, making it easy to find.

This is done via blockchain tokens, which are basically entries on the blockchain ledger that can be traded and attain value, currently at a fraction of a cent. They’re sort of like a cryptocurrency, and Lbry’s business model will depend on how they do over time; it has kept 40 percent of the tokens that will exist.

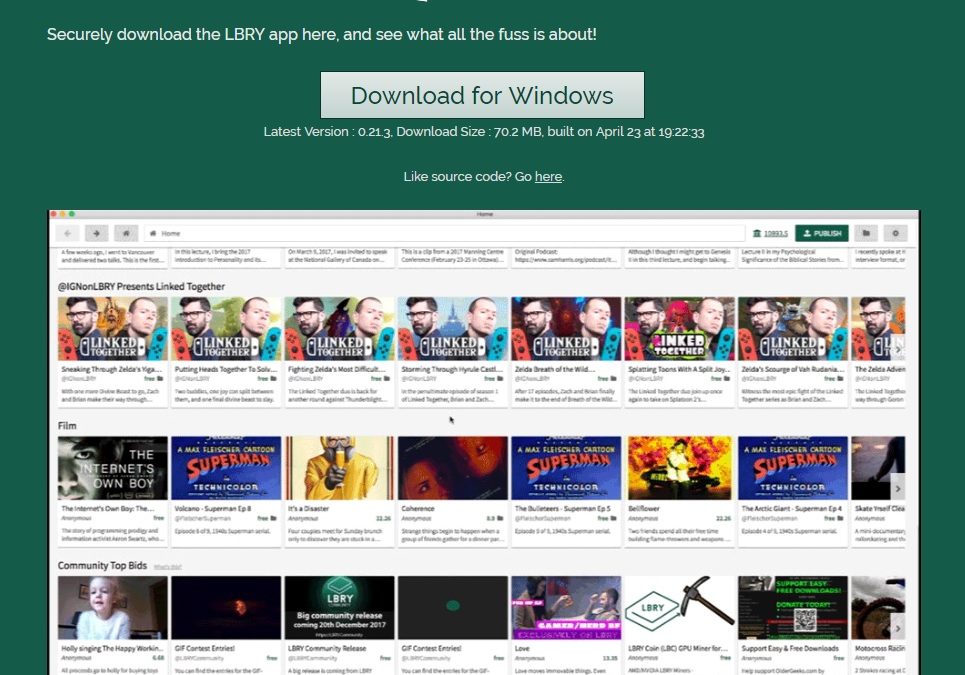

Lbry is more than just a protocol on the blockchain, however; it will live or die on the services it provides, like the app. As Kauffman knows, unless it is as easy to use as YouTube and the like, I don’t think the argument that you can avoid corporate control of your content will be enough for it to succeed.

If nothing else, it adds another interesting element to the startup ecosystem in downtown Manchester, where blockchain and domain name servers jostle with medical devices and bio-fabrication to create an entertainingly geeky stew.

Let’s just hope society doesn’t destroy itself while they create the future.

Return to the Concord Monitor

Return to the Concord Monitor