(Give you ears a treat: You can listen to me talk about this story on the low-budget Granite Geek podcast)

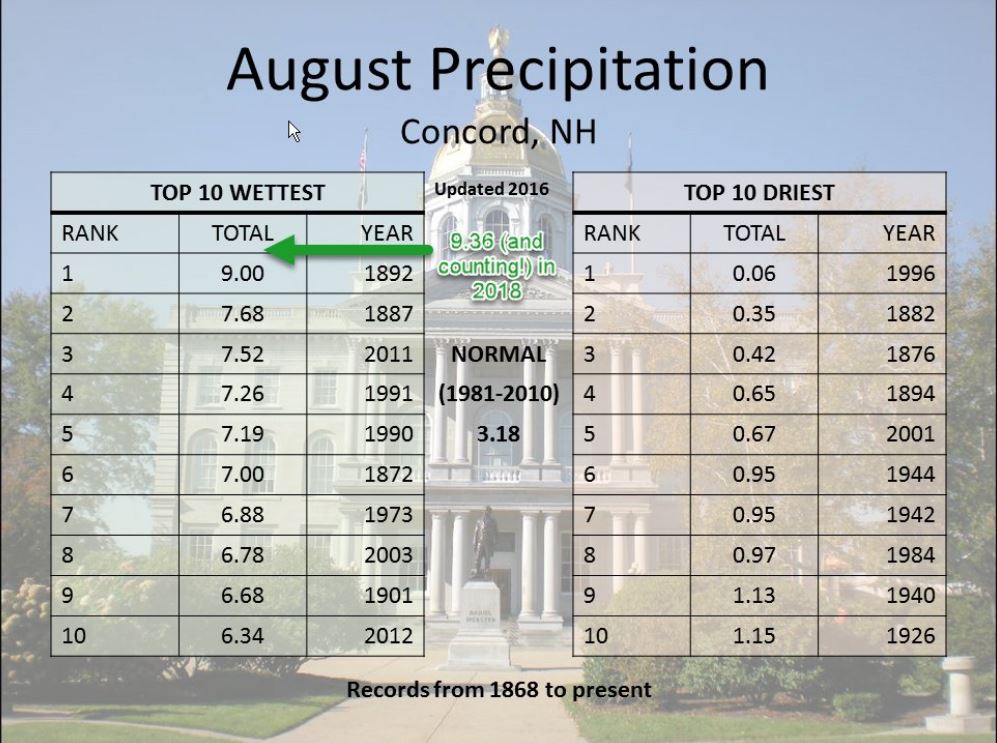

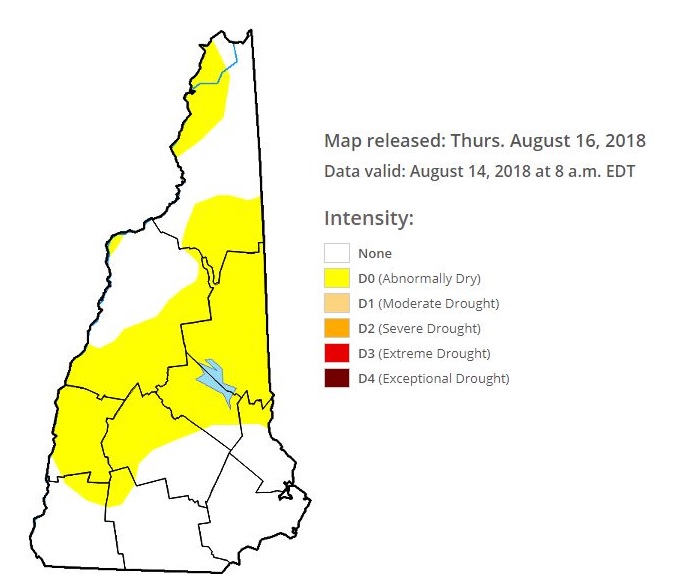

Right now in Concord, we are living in a meteorological puzzle: The National Weather Service says this is the wettest August since records began being kept 150 years ago, yet the National Weather Service also says the region is “abnormally dry,” the first stage of its drought-measurement scale.

No, climate change hasn’t driven weather folks crazy. The solution to the puzzle is that there are droughts and then there are droughts.

“There is a time lapse in how different systems respond to current conditions,” is how Richard Kiah, chief of Hydrologic Network Operations for the regional office of the U.S. Geological Survey, puts it.

In laymen’s terms: When wet weather appears, as it did in July, after a long stretch of very dry weather like we had this spring, the grass starts growing pretty quickly but it takes longer to fill up the aquifers that our wells depend on. A drought above ground might end, might even give way to flooding, while drought lingers below ground.

That’s roughly what we’re seeing now, although thankfully the drought and flooding have been minor compared to other parts of the country.

This discrepancy is a function of the “time lapse” that Kiah mentioned above. As an illustration, he pointed to the town of Warner.

USGS maintains a series of measuring devices around the state that keep track of groundwater levels, meaning how much water is available for wells, and other devices that measure how much is flowing on the surface in rivers. Warner has a stream gauge measuring flow on the Warner River, and also a groundwater well nearby.

At the end of March, which is roughly when the dry spell began, the stream gauge in Warner was measuring water flow above the 95th percentile point for that time of year, meaning more water was flowing in the river than almost late March in history. The groundwater level was almost that high as well: It was in the 90th percentile.

By mid-July, after two months of bone-dry weather, the surface stream gauge had plunged almost to the 10th percentile, meaning that nearly nine out of 10 past Julys had seen more water in the river, definitely a drought signal. Yet at the same time, groundwater gauge was still in the “normal” range, just slightly under the long-term average.

Both gauges are now trending upwards, and I would guess that in the next few weeks central New Hampshire will be out of the drought category entirely, as they are already in southern New Hampshire. It’s not straightforward, though.

The designation of drought requires more than just measuring recent rainfall or water flows. Other factors intrude, notably evapotranspiration, which is the measure of how much of the moisture falling from the ground and existing in the air as humidity is used by plants.

“At this time of year, some of the rainfall is not going to be recharging the groundwater, it’s going to be taken up by the plants and trees,” Kiah said. So even if a wet period is good for plants, fixing the agricultural drought, it may not be all that good for long-term water supplies.

All this makes determining whether we’re in a drought something of an art as well as a science, balancing the needs of plants and people today with the needs of plants and people in the coming weeks and months.

“New Hampshire’s drought management plan takes into account these things,” Kiah said.

The terminology goes from meteorological drought, due to a lack of rain, to agricultural drought, when the soil dries out, to hydrological drought, affecting groundwater and stream flows. Perhaps what should happen is that we give up on the idea of announcing whether we’re in a drought and instead announce whether we’re in any of three possible types of drought.

But probably not. That would confuse people more than enlighten them.

After all, designating a drought is as much a social and political marker as a scientific marker. It gives governments authority to impose watering bans and it motivates people to save water. Even if it isn’t always logically consistent, it’s still useful.

Return to the Concord Monitor

Return to the Concord Monitor