Harvard law professor Larry Lessig has been in New Hampshire often enough for political advocacy that he knows what will get lawmakers’ attention here, and he got right to the point Tuesday: He thinks our presidential primary is in danger.

Lessig was testifying in favor of a bill to change the 2020 primary to ranked-choice voting, which would allow people to vote not just for a single candidate for each office, but mark the ballot to rank all the hopefuls from their top choice to their bottom choice.

Lessig said Iowa was likely to change its presidential caucuses to ranked-choice voting, which would give a much more detailed picture of voter preferences, particularly among what looks to be a large field in the Democratic Party. If New Hampshire sticks with the traditional system, he argued, our primary results will be muddy and of much less value, diluting the stature of the First in the Nation Primary.

“There is a significant chance that the significance of the New Hampshire election gets destroyed because of the number of candidates running and because of Iowa’s decision,” Lessig told the House Election Law committee. “If we come to New Hampshire and New Hampshire has 10 people on the ballot, it is just noise that the New Hampshire primary delivers.”

Changing to ranked-choice voting, said Lessig, “would continue to maintain the significance of New Hampshire as a critical part of the presidential election system.”

Proponents say the systems better reflect voters’ wishes, which would reduce people’s cynicism and apathy about elections, and would force candidates to appeal to a wider swath of voters, reducing the bitter divisions of current politics.

“Most of us live in the middle. Ranked-choice voting empowers the middle, and still allows voice at the edge,” said Rik Yeames of Concord, one of a dozen people who spoke in favor of the process at Tuesday’s hearing.

Opponents say the systems are unwieldy and unnecessary, and could actually increase voter cynicism because their complexity could be seen to be a way to hide deception.

The bill in question, HB728, is one of two bills that would radically change New Hampshire ballots. The other, HB 505, would adopt a similar but less specific system called approval voting, which also lets people vote for more than one candidate for a single office. It was the subject of a public hearing Monday.

Both ideas have been proposed in the legislature in past years but have gained little traction. There’s a big difference this time around: Last November, Maine became the first state to use ranked-choice voting, also known as instant-runoff voting, in statewide elections.

That real-world example tackled many issues raised at Tuesday’s hearing – for example, Maine also has some towns that count ballots by hand rather than by machine, a concern of some committee members – and brings down to earth what can seem to be an unnecessary complication of normal voting systems.

Not that complications were absent Tuesday.

Among other things, testimony included reference to Arrow’s Theorem, which shows that no voting system is perfect and contributed to its author winning a Nobel Prize in economics, as well as the “three-stack sort system” of vote counting and mathematical systems that balance out what is known as the “shoo-in effect.”

On the legal side, a possible complication was also raised about whether the system would collide with the definition of “plurality” for state-wide elections in the state constitution.

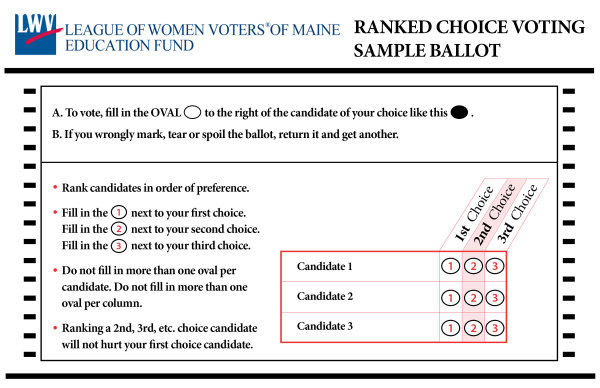

Ranked-choice voting looks like this: when more than two people are running for a single office, voters rank them from top to bottom. If no candidate wins a majority of the No. 1 votes, the least-popular candidate is dropped and that person’s votes are distributed among the No. 2 choice on their ballots. The process can continue several times until somebody gets a majority.

HB728 proposed to use ranked-choice voting in the 2020 presidential primary, and roll it out for all state elections further down the road. The system is more complicated in New Hampshire because we have multi-town districts, and would make it harder, perhaps impossible, to learn election-night results from such districts that use hand-counted ballots.

Variations of ranked-choice voting are used in national elections in countries including Australia and Ireland and in a number of cities around the U.S., as well as to choose the best picture winner at the Academy Awards.

Proponents say ranked-choice voting gives people more of an incentive to vote because they can demonstrate their feelings about candidates more precisely. Just as importantly, they say, it lets people vote for their actual choice even if they don’t think that person will win because their other rankings will still affect the outcome.

From the point of view of politicians, proponents say ranked-choice voting cuts down on extreme partisanship because candidates cannot afford to alienate too many voters.

The system could also have the side effect of making third-party candidates more viable because their supporters wouldn’t be afraid of throwing away their vote, fearing that only the two main parties ever win.

Prime sponsor Rep. Ellen Read, D-Newmarket, went a little further describing this situation when pitching her bill to the committee: “It’s the ‘lesser of two evils’ dilemma, sometimes called the evil of two lessers.”

Maine’s election in November produced one change in results due to ranked-choice voting: Incumbent Congressman Bruce Poliquin won the most top-ranked votes but didn’t get a majority, which triggered the ranked-choice tabulation. Challenger Jared Golden eventually won because more voters gave him their second choice vote. Poliquin sued, saying the system isn’t allowed under the state constitution, but the lawsuit was tossed out in December.

Lessig is known among techies for his work establishing the Creative Commons system of sharing information online. In recent years he has become an outspoken advocate of changes to the political system, twice leading hikes the length of New Hampshire to draw attention to his concerns.

Return to the Concord Monitor

Return to the Concord Monitor