Note: Despite the name similarity, QuasarWave has no relation to Quasar Power & Technologies in Belmont, NH, which is a military contractor of power equipment (milpower.com/)

The company installing a factory in a former North Country paper mill hopes to create hydrogen, which some see as the ultimate clean fuel, through a process of compression that appears unlike any existing technology in that field.

And while the company’s immediate plan is to burn the hydrogen to create electricity, the long-range plan is much bigger.

“The real intent of coming out with a power plant is because it will unveil our capabilities in a big way,” said Whitaker Irvin Jr., president and CEO of QuasarWave, the Utah firm behind the project in the closed Wausau Paper mill in the Groveton section of Northumberland. “When you’re talking about running a power plant on hydrogen … in a way to make it cost-effective … that’s not nebulous.”

Hydrogen is the most abundant substance in the universe and can be burned to release energy with virtually no pollution. Many see it as the ideal clean-energy replacement petroleum, coal and natural gas to fuel transportation, create electricity and allow long-term energy storage to supplement renewable power. The potential is so great that some talk about creating a “hydrogen economy.”

The problem is how to obtain pure hydrogen in the first place, because it bonds very tightly to other elements.

Current systems of creating hydrogen for industrial applications involve using electricity to split water into hydrogen and oxygen or, more often, combining methane from natural gas with a catalyst at high pressure in what is known as steam reforming. Both systems require a large amount of energy or produce greenhouse gas, negating the benefit of hydrogen as a clean fuel.

If QuasarWave, which also does business as Q Hydrogen, has found a more efficient way to separate hydrogen at industrial scale then the project being launched in Groveton could have huge repercussions.

Irvin attended Babson College and worked for Raytheon Corp. in Massachusetts and thus is familiar with New Hampshire. He says the decision to set up their first installation in a small town well north of the White Mountains came for pragmatic reasons.

“We were looking for places where electricity is deregulated to the extent that New England is,” he said.

Irvin said New Hampshire’s “open-door policy” to business was also a spur: “The best place to start is to take the path of least resistance.” He pointed to Anne Copp, a former state representative from Andover, as having helped make the necessary connections.

The plan for QuasarWave is to take water from the Upper Ammonoosuc River, separate out the hydrogen and burn it in a reciprocating engine to produce electricity that will be sold to companies on site. Irvin says this electricity will be cheaper than can be bought on the grid.

When the idea first surfaced a year ago there was talk of building a data center to use the electricity on site, but that has fallen through. Partly as a result, the power plant has been scaled back from 29 megawatts to 7 megawatts, which has the advantage of sidestepping the lengthy approval process from the state Site Evaluation Committee.

Details about the technology that will separate out the hydrogen, which is the whole point of the operation, are proprietary.

“It’s a turbine-based technology for producing hydrogen … involving high and low pressure, magnetics and a few other things,” said Irvin, declining to be more specific.

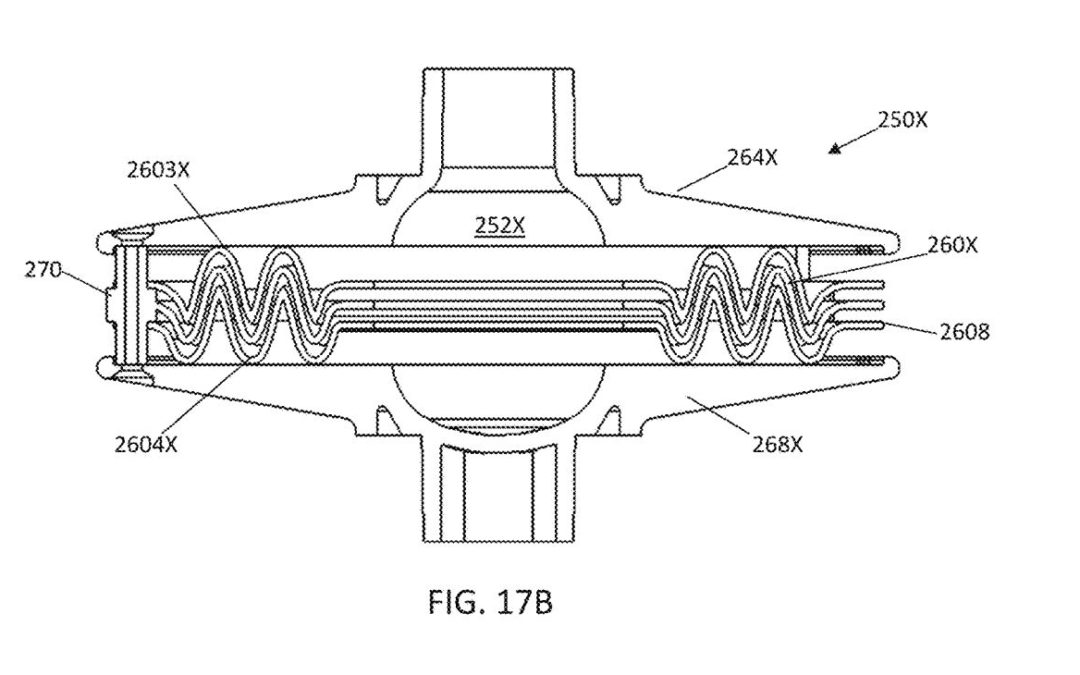

His father, Whitaker B. Irvin Sr., has taken out a number of patents over the past decade involving water treatment. The most recent, granted in November, describes a way to “process water to produce gas … using a water treatment system having a disk-pack rotating in it,” although it’s unclear if that relates to what is being installed in Groveton.

Irvin said production is scheduled to start this summer and if all goes well they’re be looking to expand beyond power production.

“We’re figuring out a first best use,” he said, pointing to current uses of industrial hydrogen in such things as making fertilizer and refining petroleum.

One high-profile possibility, of fueling automobiles with hydrogen, as is being done on a very limited scale in a few places, will have to wait, he said.

“Something like the automobile will be an important avenue, but it will take some time. Larger industrial scale is easier at the beginning,” Irvin said.

Return to the Concord Monitor

Return to the Concord Monitor

More information as it comes in. Negative consequences? I live near. I’m a huge environmentalist.

There are negative consequences to everything, of course, and I’m sure this will create at least something bad that didn’t exist before. What matters is whether the good outweighs the bad.

Definitely includes a turbo encabulator https://youtu.be/Ac7G7xOG2Ag

Hydrogen is a VERY unstable fuel and highly explosive in pure form. Its nothing you want in the trunk of your car. It is interesting they mention creating hydrogen to use in the refinement of petroleum…

Did they get the turbo encabulator working?

Seriously, did it work?