With some pushing to remove Franklin Pierce’s name from two colleges because of his support of slavery, you have to wonder about the future of a much bigger object: Mount Pierce.

Right now there doesn’t seem to be any agitation to rename that 4,300-foot peak in the Presidential Range, although I have been asked about it by a couple of readers. The issue, of course, is that while Franklin Pierce might be the only president with New Hampshire roots, he has never been held in high esteem. Many historians regard his support for slavery during his administration from 1853 to 1857 as one of the factors that led to the Civil War.

This racist history has become increasingly untenable, and recently led some students and faculty to call for removing his name from the UNH Franklin Pierce School of Law and from Franklin Pierce University in Rindge. Both of those proposals are ongoing.

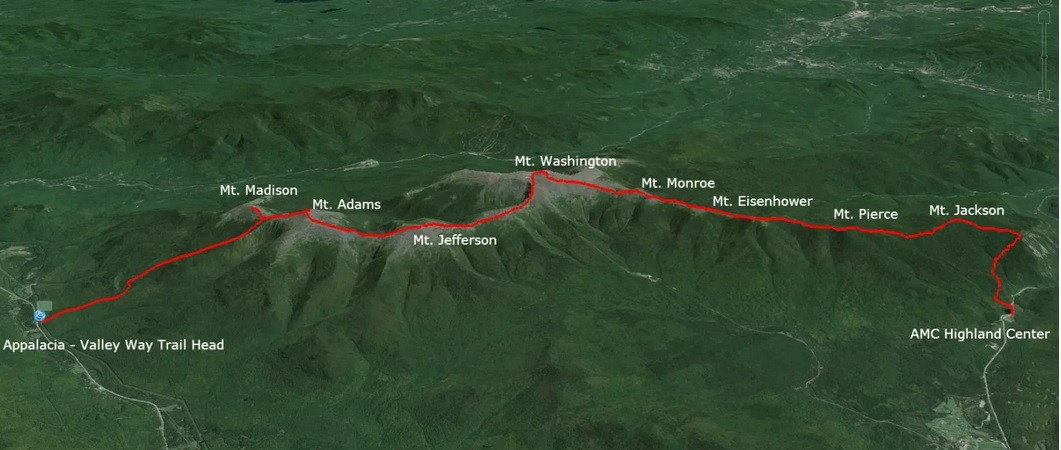

If somebody decided to extend this change to Mount Pierce, it won’t be the first scuffle over what to call the prominent peak between Mount Jackson and Mount Eisenhower.Many names

Like many high points on White Mountain ridge lines, Mount Pierce has had a number of names over the centuries.

There’s no record of what Native Americans called it, if they even gave it a distinct name.

According to “Place Names of the White Mountains,” a 1993 book by Robert and Mary Julyan, its first recorded name was Bald Hill, a common way to refer to peaks without trees. That was foisted on it by Abel Crawford, one of the pioneers of White Mountain settlement – whose name lives on in Crawford Notch and the Crawford Path that summits the mountain – and I think this lack of originality reflects the fact that Mt. Pierce is pretty nondescript among 4,000-footers.

In 1820, what is known as the Weeks-Bracket Party charged around the White Mountains with levels and other instruments to accurately determine mountain heights and in the process decided that everything needed better names, perhaps to goose the very young tourist trade. They ran out of presidents – there hadn’t been too many of them by 1820 – so this peak was named after an almost-president: DeWitt Clinton, the sixth governor of New York, who had come close to beating James Monroe a decade earlier.

Fast forward to 1913. The New Hampshire Legislature decided that the Presidential Range needed to include our own president, so they voted to turn Mount Clinton into Mount Pierce. The U.S. Board on Geographic Names quickly agreed.

However, not everybody was happy with the change, most importantly the Appalachian Mountain Club. In 1915 the AMC Committee on Nomenclature voted to keep “Mt. Clinton” on its maps, which then as now are the go-to source for most people traversing the North Country.

I’m not sure why they objected to Mt. Pierce aside from being irritated that New Hampshire dared to override them (AMC is headquartered in Boston).

I asked AMC Archivist Becky Fullerton but she said no committee meeting minutes survive from those days. “Now that you’ve asked, I’m dying to know, too! What did they have against Pierce?” she wrote in an email.

As for Mount Pierce, the nomenclature distinction lasted at least through my wife’s copy of the 1969 AMC White Mountains handbook, which lists the peak as “Mt. Clinton (Mt. Pierce).”

The AMC eventually came around: the White Mountain Handbook we bought in 1992 lists it as “Mount Clinton, see Mt. Pierce,” while our 2012 handbook doesn’t mention Mt. Clinton at all.

Actually, that’s not quite true. There’s one remnant of the change: Mt. Clinton Trail, which heads up Mt. Pierce and I’m sure continues to confuse hikersbaffles many a hiker who can’t figure out how to summit Mt. Clinton.Making changes

The process for renaming things like mountains, lakes and rivers is pretty straightforward: Just ask the U.S. Board on Geographic Names. There is a web form at geonames.usgs.gov with lots of room to explain why you want to make the change.

Proposals are circulated for comment among relevant towns, counties, Native American tribes, state agencies and others, said Ken Gallagher, who works for the NH Office of Strategic Initiatives and heads up the State Names Authority. That group coordinates name-change requests for the federal board that makes the final decision.

Name changes happen a couple times each year, doing things like recognizing Snow Dragon Mountain as distinct from Ladd Mountain or removing the “k” from Lake Wickwas, now Lake Wicwas. About a quarter of proposals don’t get approved, including the idea of turning a nameless Franconia waterfall into Moose Antler Falls or creating a Pocahontas Cove in Sandwich.

Usually name changes draw little attention beyond the immediate area but there are exceptions. One was the 2012 decision to rename Jew Pond, a small man-made body of water in southern New Hampshire. That debate attracted reporters from as far away as Israel.

Another high-profile debate was the Legislature’s 2003 proposal to rename Mt. Clay as Mt. Reagan. That was turned down by the Board of Geographic Names after some opposition from locals, even though Henry Clay wasn’t a president and Ronald Reagan was.

There seemed to have been no argument in 1969 when Mount Pleasant, a name even more boring than Bald Hill, was renamed Mount Eisenhower.

I’m sure that if anybody ever does seek to remove Pierce’s name from the mountain it will get a lot of attention as well. An important part of the request would be a replacement name.

“The proposed name must not be for a living person or one who has been deceased for less than 5 years. It should not duplicate any other nearby name. (There are lots of Mud Ponds in New Hampshire already, no need to add another one),” Gallagher said in an email. “There is a lot of room on the web form for making the case for the proposed name – historic usage, current usage, connection to the place being named, etc.”

There are lots of presidents to choose from now and since the last dozen or so have spent lots of time campaigning in New Hampshire they even have a local connection.

Of course, there’s always the possibility of reverting to the 1820 name, although with a different Clinton in mind to fit the presidential theme, posthumously of course. Then I could reuse the 1969 guidebook!

Return to the Concord Monitor

Return to the Concord Monitor

Jimmer Carter has done more philanthropic work after his presidency than any other. Mount Carter sounds good to me.

Re: Mount Carter

A worthwhile thought, but probably too confusing, with Carter Dome not too far from there, not to mention North, Middle and South Carter further along.

How about Mount Mizpah? Maybe a little backwards, naming a mountain after the nearby AMC hut, but …

If Mt. Pierce’s name is changed, then that would justify quite a few more changes. Mt. Washington for one, since George owned slaves even while President of the U.S. (Doesn’t that make him pro-slavery?) and also Mt. Jefferson (Thomas Jefferson owned slaves while President) Mt. Madison and Mt. Monroe (since both James Madison and James Monroe owned slaves while President), and last but not least, Mt. Jackson (Andrew Jackson owned slaves while President). Note that I am NOT saying that I think any of these mountain names should be changed, just saying that if you change one, you might have to change them all for the same reason.

It wasn’t that he owned slaves – I’m not sure if he did – it’s that he supported slavery at a time when the abolition movement was growing, allowing its expansion into new territories and (many argue) making it impossible to avoid the Civil War.

Dave, Franklin Pierce in fact did not own slaves. I guess my point is that if Mt. Pierce is changed, all those other Mountains could easily be argued to need a name change. The debate could be, which is worse–actually owning slaves, or promoting policies that promoted slave ownership. I’ve read that Franklin Pierce College is going to change its name so that part is moot. We’ll see what happens ….. Great article, whatever happens, a mind-bender.

How could Pierce have been pro slavery, when (in his Presidential State if tge Union Address claimed that ‘Human Slavery is one of the worst things that ever hit the face of this planet?

Riggt?

From the inauguration: “I believe that involuntary servitude, as it exists in different States of this Confederacy, is recognized by the Constitution. I believe that it stands like any other admitted right, and that the States where it exists are entitled to efficient remedies to enforce the constitutional provisions,”

Once in the White House, Pierce backed the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, which overturned the Missouri Compromise of 1820. The Act repealed of the prohibition against slavery in territories north of the latitude 36 degrees 30 minutes, and allowed voters in territories to decide if they wanted slavery. … Pierce also intervened on behalf of pro-slavery interests in the Kansas fight.