While it’s true that receiving an award from the president, having a statue in your honor put up in your hometown and being featured in the nation’s most prominent museum are impressive achievements, you haven’t really made it these days until you’re the subject of a children’s picture book.

Ralph Baer, New Hampshire’s video game pioneer, has made it.

The Boy Who Thought Outside the Box tells how Baer began as a radio-set tinkerer in pre-Hitler Germany, served in the U.S. Army (more radio tinkering), led a team that lurked under the radar at a Granite State defense contractor and figured out how to turn one-way TV sets into two-way game consoles, and finally became a successful inventor/entrepreneur working out of his Manchester basement.

It’s about as American a biography as you can get.

One aspect of the story that will tickle New Hampshire readers is how bosses at Sanders Associates in Nashua – now part of BAE Systems – shot down Baer’s ideas about interactive TV and how he eventually set up a three-person “secret laboratory” in the company’s Canal Street offices to develop it.

Sanders Associates made millions after they sold the idea to Magnavox, which turned it into Odyssey, the first home video game. But when I first came to Nashua, the company didn’t say a word about it, like a prominent family embarrassed that their wealth came from a disreputable industry.

Only in recent years has BAE changed its tune, holding up Baer’s story as a lure to job-seeking engineers.

Much of the story in The Boy Who Thought Outside the Box will be familiar to us in New Hampshire but it was news to the author when she started out.

“My son, who has been a reluctant reader since he was a little guy, read a book about Lonnie Johnson, who invented the Supersoaker, and really enjoyed it. That prompted me to think – what are some other toys and games that kids like?” said Marcie Wessels, a California writer.

While growing up, Wessels says she had an Atari, the creation of Baer’s arch-nemesis Nolan Bushnell, and had never heard of Ralph until the research began.

“I was floored. Here is someone who was largely unrecognized for the steps he made in the development of video games,” she said.

This is not an uncommon reaction, although it’s less common than it once was.

Baer, who died in 2014 at age 92, worked in his golden years to get more recognition. Video-game fans were already idolizing Baer by the time I learned of him in the early 2000s. Then he received the National Medal of Honor from President George W. Bush in 2006, and after he died, the Smithsonian packed up the basement workshop from his modest Manchester home and put it in the National Museum of American History.

Family members have continued the push, and his charmingly casual statue on a bench in Manchester’s Arms Park is one result of that.

Baer is remembered not just for creating, with engineers Bill Harrison and Bill Rusch, the Magnavox Odyssey but also for his independent creation of Simon, the pattern-memory light-up game that was a national sensation in 1977, and an interactive talking teddy bear that battled with Teddy Ruxpin for leadership in that odd category of toys during the late 1980s.

With an eye toward her primary-school audience, Wessels concentrated on Baer’s early days in the book, published by Sterling Children’s Books. In Germany, she says, he was picked on both because he was Jewish and because he was a bit of a nerd.

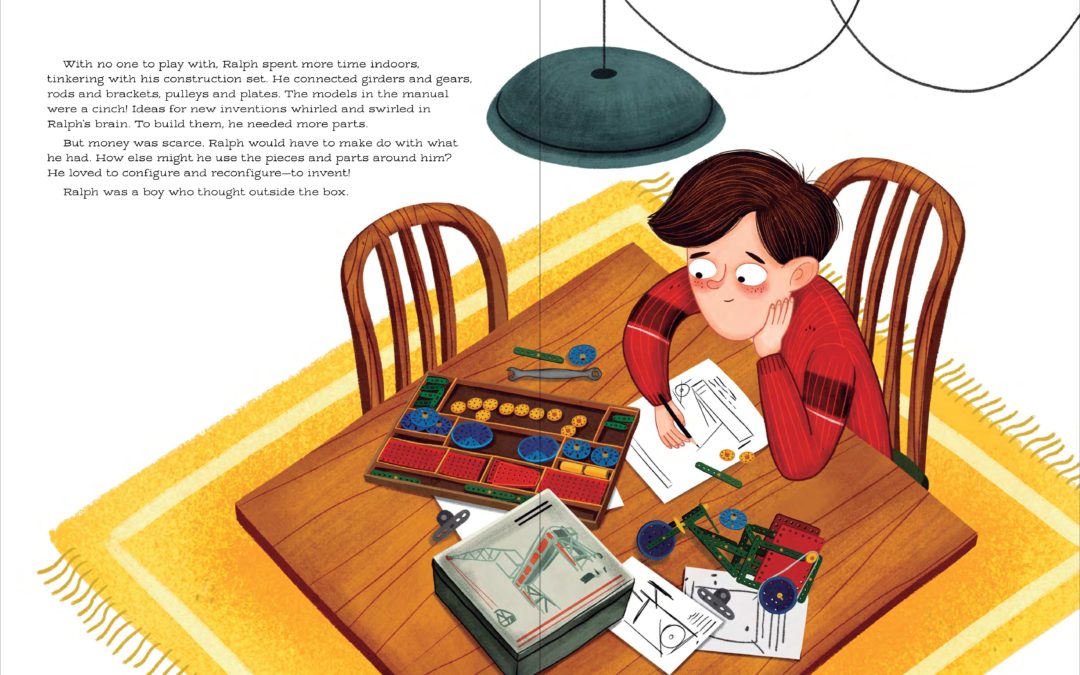

“With no one to play with, Ralph spent more time indoors, tinkering with his construction set,” she writes, noting that lack of money forced him to, as she says, “think outside the box.”

That continued after his family fled Hitler in 1938.

“At the very heart, he was a very playful person: What can I do to make this better, what can I change?” Wessles said.

Wessels says she found the story compelling enough that she’s putting together a chapter-book version for older kids and developing curriculum around his life as a STEM spur for schools.

That would be very appropriate. Ralph was nobody’s pushover – he reamed me out over the phone once when I wrote a story he didn’t like – but intelligent play was a joy to him.

If you could have fun doing something but also figure out how it could be done better, he was delighted. A year or so before he died Ralph got excited showing me an interactive bicycle-noise-making gizmo he was developing.

It was an interesting problem, a clever solution, and an entertaining result. What more could you ask from life?

Return to the Concord Monitor

Return to the Concord Monitor