In fossil-deprived Northern New England, where geology melted dinosaur remains and glaciers ground up everything else, woolly mammoths are special. (Addendum: They’re so special that a project at Harvard called Revive & Restore is trying to use genetics to revive them.)

Mammoths and their mastodon cousins are the only extinct megafauna that were definitely here at some point. Solid evidence exists in the form of teeth from a couple of places in New Hampshire and teeth or bones in a few other New England spots.

This makes it even more delightful that just-published research gives the first indication that the first New Englanders might have encountered these big beasts.

“This in no way proves that humans and megafauna interacted in New England or even that they saw each other. But it makes it more probable,” said Dr. Nathaniel Kitchel, a postdoc in the Dartmouth College Department of Anthropology.

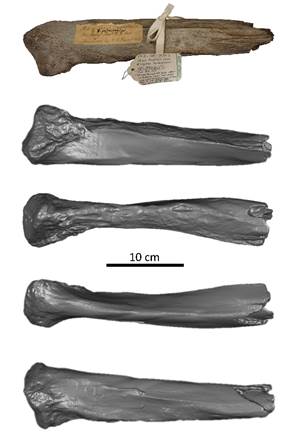

Kitchel and Dartmouth Anthropology Prof. Jeremy DeSilva have just published a paper that gives the first good radiocarbon date for a woolly mammoth fossil in New England. Previous samples haven’t had enough organic material to be dated.

The dating was done on a portion of rib from what is known as the Mount Holly mammoth, which was uncovered in Vermont in 1848 during construction of a railroad line. Kitchel found the rib in the warehouse of an art museum, of all places. More on that in a moment.

According to their paper, published in Boreas, a journal of research about the Quaternary Period, the radiocarbon dating shows the rib was part of a living animal about 12,800 years ago. By anthropology standards that’s not long after the Ice Age retreated and is reasonably close to when humans arrived. In other words, people and mammoths might have shared the glacier-scarred landscape!

By the way, this paper definitely does >italic<not >res<say that people showed up and then mammoths disappeared, therefore the first caused the second. Kitchel emphasized that point.

“In no way am I trying to imply that humans had anything to do with the demise of this creature,” he said. “That’s a fraught discussion.”

Indeed it is. I have a couple of books arguing whether or not the first humans drove big mammals to extinction in North America. We will take no sides in the debate.

“Think about how different a world Vermont and New Hampshire were at the end of the last Ice Age. Much of Northern New England probably didn’t have any trees at that point, after the glaciers, and there were elephants walking around!” he said. “It was pretty Arctic-like, really.”

The origin story of this discovery involves what Kitchel says was “luck, honestly.” It is a perfect example of Louis Pasteur’s adage that chance favors the prepared mind.

As Kitchel tells it, in December 2019 he was going through the offsite storage facility of Dartmouth’s Hood Art Museum looking for items that might be useful in an introductory anthropology class he was teaching.

“They have a relatively small but interesting collection of artifacts from the Northeast gifted to them by various folks over time. They have a lot of what folks might call arrowheads – bifacial knives, projectile points, depending on what they were used for,” he recalled.

“I was walking down these big shelves looking for things when I see this large bone in the New England materials. I thought, that’s quite odd but it could be a Colonial-era cow bone, something like that. I just happened to reach over and flip over the tag and it said Mount Holly Mammoth on it … and I reacted!” he aid.

Kitchel, who grew up in Vermont’s Northeast Kingdom, knew all about the Mount Holly Mammoth, which is Vermont’s state terrestrial fossil. (A beluga whale is the Vermont state marine fossil, if you’re wondering. New Hampshire doesn’t have any state fossils although not from lack of trying.)

“The primary story was that most of the bones, tusks and teeth went to Harvard but there was no record of anything going to Dartmouth,” he said. His interest piqued, he sent a sample off to a radiocarbon-dating lab and got the results right before COVID-19 shut everything down.

“It’s a very basic paper: we’ve got a mammoth, how old is it?” said Kitchel. But that doesn’t mean it’s not significant.

“I grew up in northern Vermont and that wasn’t on my radar as a kid, that this landscape was once inhabited by woolly mammoths. I think it’s cool that at least in this small way … we can show some of the really deep history of the region that we don’t often hear about.”

Return to the Concord Monitor

Return to the Concord Monitor

Very interesting. I always thought these mammoths were only in the Western part of the US.