There’s a pretty good chance that right now, as you’re reading this, at least one business owner in New Hampshire is freaking out over ransomware.

“Yeah, it’s happening daily here – weekly for sure,” said Jason Golden, a partner at Manchester cybersecurity firm Mainstay Technologies.

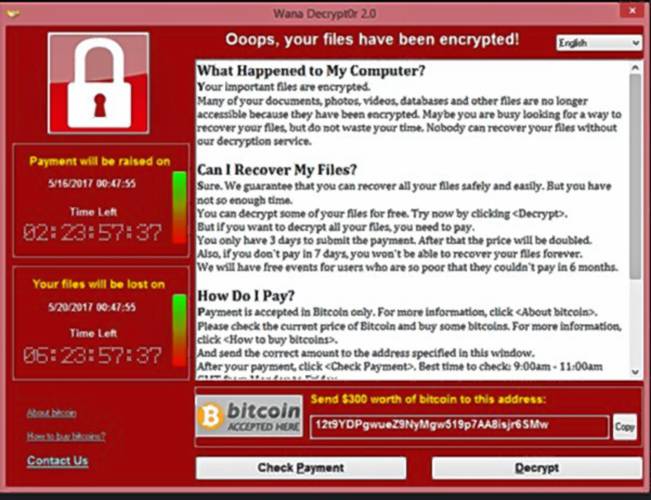

Ransomware is the catchall term for outsiders getting access to the computer network of a company or organization and locking it down with cryptography, then demanding a ransom to unlock it. It has been around for years but is getting a lot more attention these days due to attacks on big companies like Colonial Pipeline and the beef processor JBS. I was curious about how much it happens to companies in New Hampshire.

The answer: Nobody knows.

There is no data because there’s no requirement that it be reported, and companies understandably won’t publicize their problem unless forced to. But undoubtedly it’s a big and growing problem, here and elsewhere.

“It’s the thing we fear the most,” said Denis Goulet, commissioner for the state Department of Information Technology. “On a federal level, they’re starting to look at it as a national security problem, rather than just a problem for the individual that gets hit.”

Just last week the state Insurance Department issued a cautionary note about ransomware, with Commissioner Chris Nicolopoulos saying, “It is critical for insurers to protect against these threats.”

“Cybersecurity people can be rightly criticized for being hyperbolic and overstating the case. However, I don’t think it’s possible to be too hyperbolic when it comes to ransomware threats. On a 1-to-10 scale, it’s 12,” said Ryan Robinson, another Mainstay partner.

Along with freaking out, what’s a business owner supposed to do?

Because ransomware involves computers, most of us think it’s an I.T. (information technology) Department issue. But that’s not a great way to think about it, say the Mainstay folks, because bad guys almost always get access to a firm’s network via a mistake made by a person working there – clicking on the wrong link in an email, as often as not – rather than through gee-whiz computer coding or zero-day exploits.

“I.T. is about your switches, firewalls, devices, technical controls. Information security is about your organization, your policies and procedures, your users and their behaviors, your financial controls,” said Robinson. “It’s a different way of even thinking about the problem – not just let’s get a better firewall, better web-filtering.”

Among the companies doing such thinking is the Monitor.

“Once you’re beyond a certain size – number of employees – it’s extremely difficult to stay safe,” said Tundra Slosek, telecommunications manager for Newspapers of New England, the family-owned chain that owns the Monitor. “We try as much as possible to minimize the permissions that people have but it’s a back-and-forth constantly.”

Slosek pointed to the principle of “least privilege,” which says that everybody on a network should have the ability to do only what they need to do and nothing more. That way, if somebody clicks on a bad link, the ransomware will be contained.

Easier said than done because nobody (who, me?) wants to be constrained.

“The push from most users is: I don’t want the system to get in the way of what I need to. Managers’ push is: I can’t define what this person is going to do tomorrow. … Both I.T. and users get exhausted – there’s a fatigue about dealing with security,” Slosek said.

I am definitely one of those users who whines about passwords and access limitations but at least I’m not really a good ransomware target. I don’t have editor privileges in the system so I can’t keep tomorrow’s paper from being produced, and I don’t have access to valuable stuff in advertising and accounting like customer data or payment information. If Cyrillic-alphabet-using ransomware baddies locked down everything that I can get to, the Monitor would work around it rather than pay up.

Who is a good target?

“Often we see this violated the most is at the top. The CEO assumes I should have access to everything, I’m the CEO, the business owner, director of the nonprofit – and guess who is the most likely to fall for the ransomware?” said Robinson. “It’s the CFO (chief financial officer) who has access to the financials, the comptroller, the CEO – their master key is getting stolen and then (hackers) can get anywhere.”

Business – and you and me – should be doing basic things like backing up data and keeping backups separate, patching and updating software, and not letting networks overlap unnecessarily (there are cases where ransomware snuck in via some “smart” device on the network). “A lot of small business environments are flat. Once you’re in, everything is stored on the same system,” said Golden.

Beyond that, however, it’s the unending people stuff that’s required. Training people, testing plans, having somebody responsible for digital security (“sometimes it’s just an office manager who’s also doing I.T.” said Golden), keeping yourself updated. It’s a pain the neck and an extra expense at a time when many companies can’t afford it.

But it’s also a pain in the neck to buy door locks and keep track of who has which keys and to pay for security cameras and burglar alarms. Now that networks and computers are as important to business as buildings and trucks, I’m afraid that’s a pain which will just keep growing.

Return to the Concord Monitor

Return to the Concord Monitor

Great story, and timely! The day you posted this, UMass Lowell closed due to an IT breach of some kind. Not just the IT systems, mind you; the whole campus. They say they will be partially operational tomorrow, June 21 — 6 days later.

At DataSecure, we work with local NH and MA small/medium businesses to ensure they don’t lose access to their data. We advise them to assume at some point they will be hit with ransomware or similar, then work with them to ensure their data is always recoverable. Usually that’s by having multiple copies of their data in multiple formats and in multiple locations, automatically duplicated, and professionally managed. This sounds like overkill but it usually costs a fraction of the ransom, or losing the data altogether.