In my town, a property owner recently had a tussle with the planning board because of the direction of water flow.

If you poured a bucket of water onto the ground in one part of the land she wanted to subdivide, it would eventually flow into an unimportant bog. But if you walked 100 yards and then poured the bucket, the water would end up in a protected brook even though you were standing in the same field.

Ergo, she was restricted to five-acre lots rather than the two-acre lots she wanted because fewer houses are less likely to produce septic and fertilizer pollution that would end up in the brook. She was not happy but such is the power of watersheds.

I mention this because the Concord region is getting a good look at the importance of these invisible entities, and the difficulty of improving them, as we try to figure out how to fix Turkey River.

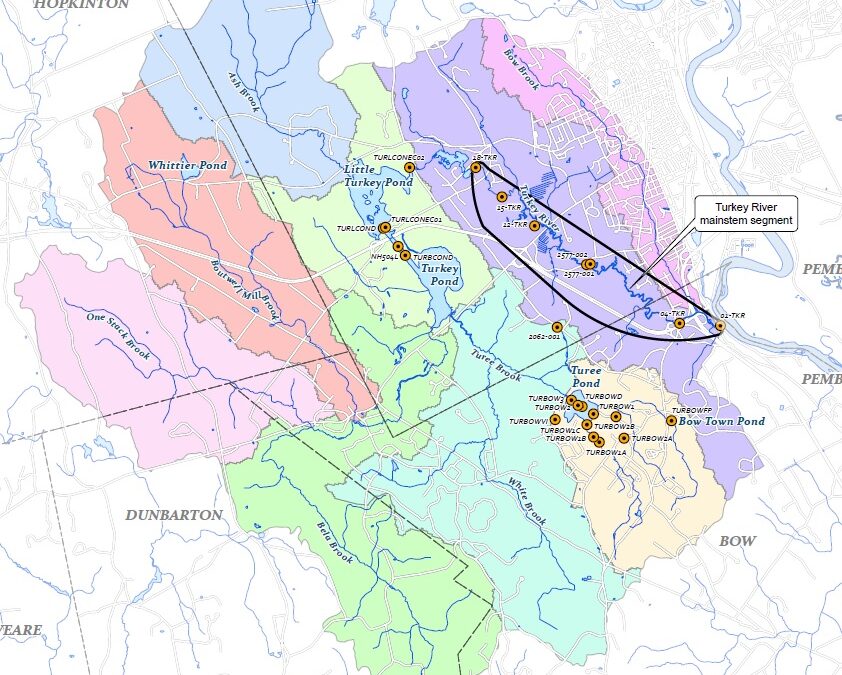

Attention is focused on the main stem of the river in Concord, defined as the waterway running south from Library Pond through St. Paul’s School, under Route 13 and under the I-93/89 interchange, ending up at the Merrimack River.

Phosphorus is the nutrient that this report uses as a basic metric. Turkey River’s level is around 30.5 micrograms per liter, way above the state average of 14, but there isn’t a lot of data. One of the main recommendations of the draft is to increase the number of data-gathering sites, since you can’t stop a problem if you don’t know where it is.

As detailed in a final draft Turkey River Watershed Restoration and Management Plan, rolled out last week, eight named brooks in Dunbarton, Hopkinton, Bow and Concord feed into Turkey River, most flowing through the two Turkey Ponds. Whatever happens in the watersheds of these six headwater streams will eventually affect Turkey River to some extent, which means that protecting the main stem isn’t enough; you need to think about everything that flows into all those brooks.

“That’s where the most attention needs to be focused to make sure that development … and stormwater management is done wisely,” said Bob Hartzel of Comprehensive Environmental Inc. He is the primary author on the plan and spoke during an online presentation about it hosted by the Upper Merrimack Watershed Association, the lead organization on the project. Final approval of the plan is expected soon.

Stormwater management in such a large area is easier said than done. The entire Turkey River watershed covers 37½ square miles, from the built-up environment of Bow Brook paralleling Main Street to the wooded ruralness of delightfully named One Stack Brook. (When I first saw the map I thought it was One Snack Brook, which would be an even better name. So would One Stuck Brook.)

Much of these watersheds are undeveloped but they won’t stay that way. We can’t stop development and don’t want to – house prices are insane enough as it is – but a watershed management plan is one way to help officials and regulators limit the unintended environmental consequences of that future development.

There are about two dozen watershed active management plans in the state. This one is typical, bristling with details about everything from rainfall history and waterfowl loading (a euphemism for bird poop) to all-important land use.

Among the immediate recommendations in the plan are changes to existing development to reduce such runoff. For example, it suggests repairs to the crumbling ramp and parking area at the Turee Pond boat launch so that less material enters the pond and thence to Turee Brook.

Another suggestion seems almost comically minor: Getting the maintenance crews at Concord District Courthouse to stop mowing the grass right to the edge of the water.

“That’s a good example of what you don’t want to do on the bank of a river,” Hartzel commented. Keeping vegetation growing along the bank of a creek or river creates a natural buffer that can absorb pollutants before they enter, which is a lot cheaper than removing them after they do.

This is why lakeside homeowners are always mad at the state: They want to get a clear view of the water by hacking down all the trees and brush but environmental officials say no because that increases the chances that water will end up algae-covered or otherwise polluted. It’s a classic environmental clash of immediate, focused desire vs. communal, long-term result.

Another important benefit, the plan said, is to build a rain garden or holding pond at Abbott-Downing School to contain water washing off the parking lot that carries sediment, oil and other waterway-damaging material. In fact, just about the best way to protect all waterways is to prevent water getting into them directly from so-called impervious surfaces, including roofs.

And then there are culverts – 88 of them that the state has examined, although there are certainly more – and septic systems, which number by the thousands, each a potential phosphorus-and-nitrogen-leaking bomb. That’s a lot to think about.

All these are covered under the clumsy phrase “non-point-source pollution.” Small individual problems spread out over tens of square miles can add up when they get concentrated in one place, like the Turkey River. That’s why watersheds, those impossible-for-us-to-see boundaries, are so important.

Return to the Concord Monitor

Return to the Concord Monitor