As New Hampshire hunters prepared for the muzzleloading season of white-tailed deer that started Saturday, their excitement reflects a surprising aspect of modern hunting: Fewer people are doing it, but they’re using a wider variety of methods when they do.

Last year, in fact, hunters killed more deer in the Granite State with a bow and arrow or muzzleloaded gun than with modern rifles. But these were not the bows or blunderbusses of centuries past.

“It’s like cellphones: The technology just keeps increasing,” said Peter Beard, 71, president of Deering Fish and Game and a lifelong hunter.

Consider muzzleloaders, which are guns where the power and bullet must be pushed down the barrel with a ramrod and fired by a separate primer. Modern ammunition combines all those in one bullet that can be loaded at the breech.

This brings up images of a Pilgrim’s wide-mouthed gun that was lucky to hit the broad side of a barn after slow, laborious loading, and only if the power hadn’t gotten wet. Today there are moisture-proof powders in pellets and “inline” guns that allow the primer to be easily handled.

“It started out as primitive firearms. People were hunting with flintlocks, cap and ball, mostly a smooth-bore gun. It has changed to a high-tech science,” said Beard. “I have a muzzleloader that will shoot 100 yards with a one-inch group … It’s really no different than a single-shot rifle.”

Rifles are much more accurate at long distances than muzzleloaders, but that’s less important in New England.

“In New Hampshire, where our woods are pretty thick, most hunters rarely have long-range shots. … Current muzzleloaders are plenty accurate within 100 yards or more,” said Dan Bergeron, Deer Biologist and Game Program Supervisor at the NH Fish and Game Department.

“Most of the deer I’ve ever taken have been during muzzleloading season,” he added.

As for bows, this ancient weapon has undergone even more change in the past four decades.

“In the ’70s, if you were bow hunting, it was with a longbow or a recurve,” said Beard, referring to the types of bows used for millennia. “Nowadays you’ve got these compound bows.”

Compound bows use a levering system of pulleys and cables to help draw back the string, allowing much more power to be exerted without more effort, and for the bow itself to be made stiffer and more consistent. Combined with sights and other technologies, they are vastly more effective.

Or you can even go further.

“I’m 71; I’ve had shoulder surgery. I have a crossbow,” Beard said. “I don’t like using it … but it (fires an arrow) at over 400 feet per second, and with the scope you can shoot an arrow 100 yards.”

Hunting decline

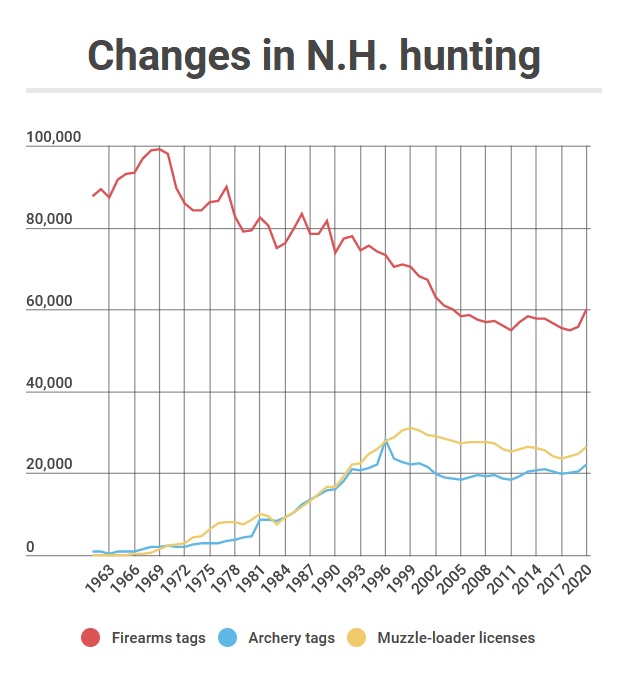

The growth in usage comes in contrast to hunting as a whole, which has been on the decline here and throughout the United States for decades. Since a peak in the late 1960s, the number of people getting a license to hunt in New Hampshire has fallen by more than 40%, from roughly 99,000 to 55,000.

he decline has been attributed to many things, mostly society’s growing urbanization and the increase in competing outdoor and indoor activities. During pandemic lockdowns, when people were desperate for socially distanced activities, the number of hunting licenses grew about 10% last year to 60,000, although it’s not clear whether the increase will stick. The number of fishing licenses sold last year grew even further, almost by one-third.

Over recent decades, the number of people buying the state license or tag to hunt with a bow and arrow or a muzzleloader gun has increased from almost nothing in the 1960s to between 25,000 and 30,000 muzzleloading licenses each year and around 20,000 bow-hunting tags by the turn of the millennium. Numbers have remained at that level for two decades even while total hunting declines.

Most of these various licenses go to the same people – that is, the muzzleloading and archery hunters are usually rifle hunters as well. But hunters seem to be spending more time, or at least getting more results, with the older tech.

In 2020, 5,798 deer were killed by firearms compared to 3,785 by archery and 3,166 by muzzle-loader.

For doe hunting, archery is by far the most successful method.

Different season, different experience

Even with the new technology it’s easier to bag a deer with a rifle, so if your goal is to quickly get venison or a trophy, you’ll avoid the older methods. Hunters use them partly for the challenge but also because it extends the season.

Archery, which has the lowest success rate per hunting trip, has the earliest and longest deer season, starting Sept. 15 and lasting two months. Muzzleloading comes next, starting at the end of October and running 10 days, while firearm season doesn’t begin until Nov. 10 and lasts about three weeks. Details vary depending on where you are in the state and whether you’re seeking deer with or without antlers.

“I see it as an additional 10 days to be in the woods,” said Beard.

Being out early is a different experience in many ways, and not just due to warmer temperatures. There are more leaves on the trees so it’s harder to scout game, but deer haven’t been spooked by weeks of hunting so they are more casual in their habits. Bucks may still be in rut, which can make it easier to lure them.

The cost of equipment and ammunition is usually less for muzzleloaders and bows, although a hunter can spend a fortune if they get carried away no matter what they’re using.

New Hampshire’s deer-hunting seasons are adjusted annually by New Hampshire Fish & Game (the legislature did it decades ago, but the deer herd plummeted and biologists managed to wrest away control). The goal is to keep a healthy herd. That’s why hunters are now allowed to kill more deer in southern New Hampshire, where the herd is becoming a pest as much as a part of nature, especially in Rockingham County.

Whether changing hunter habits and improving technology will require bigger changes down the road is unclear. In the meantime, make sure to wear a bit of blaze orange clothing when going into the woods through December.

Return to the Concord Monitor

Return to the Concord Monitor

Nice article. It’s great to get out