If New Hampshire wants to tackle two of the biggest problems facing us — the climate crisis and painfully expensive housing — we need to make it easier to not follow in my footsteps.

My problem? I live in a big single-family home on more land than I need and everybody around me is in the same situation because we’ve created a system where it’s virtually unavoidable.

What New Hampshire needs — what most of the country needs — is some variety, some freedom of choice for buyers and renters. This would create more chances of finding affordable places to live and it might, as a side issue, help us reduce our greenhouse gas emissions.

Cue the pitch for “missing middle” housing.

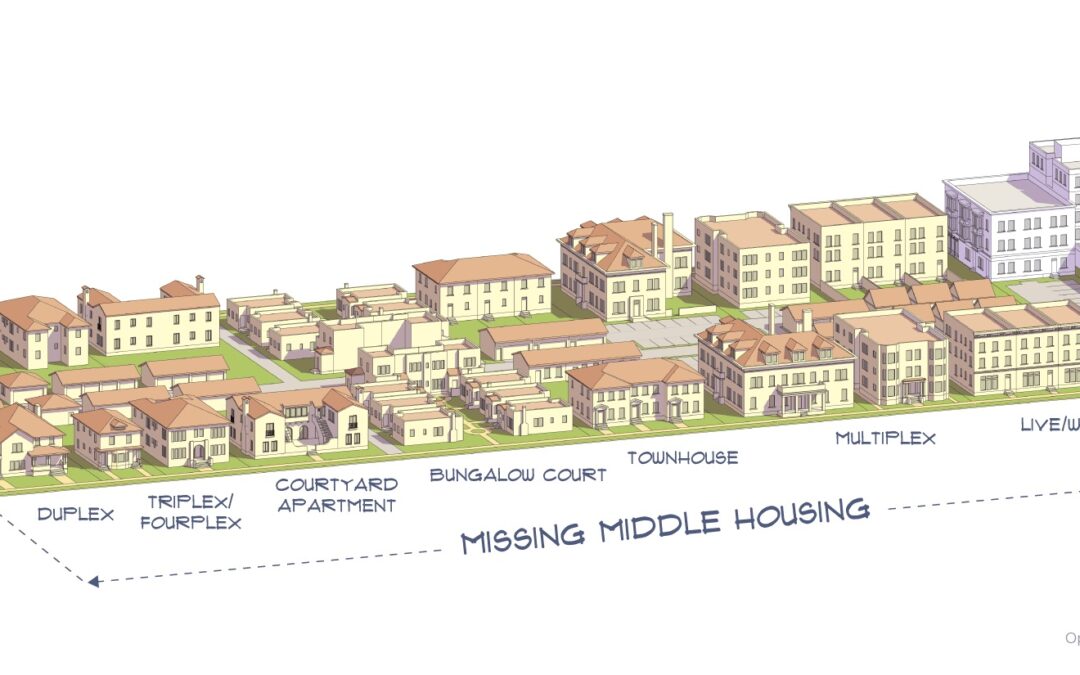

That catchy term describes places where more than one household shares a parcel of land or a structure and the buildings aren’t too big, usually no more than three stories. In other words, everything between single-family homes and apartment buildings, which are the only types of housing available in most of the state.

“This is about not shoehorning people into the few solutions that the market thinks are the best solutions,” is how Karen Parolek, CFO of a company called Opticos Design that is one of the leaders in this market, put it in a recent webinar sponsored by New Hampshire Housing.

Missing middle housing can be duplexes, triplexes, courtyard apartments, bungalows, carriage houses, live-work scenarios, old-timey apartments above the store, and more. It’s the kind of housing that makes neighborhoods possible and is increasingly attractive both to younger folks (I can walk to a bar!) and empty-nesters (I don’t have to mow so much yard!).

It’s also cheaper per unit than a 2,500-square-foot Colonial in the middle of a big lawn, which is why it interests New Hampshire Housing, a non-profit corporation that seeks to increase affordable housing.

Chunks of “missing middle” housing do exist in the state, mostly in village centers or some city neighborhoods, but little of it has been built since World War II, when zoning regulations that practically mandate suburban sprawl by separating uses (residential here, commercial over there) began to take off.

Today, no New Hampshire developer can afford to build anything other than big apartment buildings or big houses spaced far apart because of zoning restrictions, density limits, parking mandates, floor-area ratios and the high cost of land, not to mention local opposition spurred by the belief that prices of existing homes will plummet if anything different is built nearby.

We see the result in home sale data because big, separated houses are inherently expensive. “It is impossible to deliver single-family homes at affordable prices any more,” is how Parolek put it to the roughly 400 people watching the webinar.

So how can New Hampshire encourage the missing middle? Partly with laws.

We’ve seen a few baby steps in recent years, notably the easing of limits on accessory dwelling units, a.k.a. “in-law apartments.” Two bills before the legislature right now would go farther.

HB 1177 would increase the number of residential units in a single-family zone from 1 to 4 — in other words, allow duplexes and more — while SB 400 creates a package of changes aimed at increasing “incentives for affordable housing development.” From my reading, SB 400 would make it slightly harder for planning boards to turn down every development that doesn’t look like Beaver Cleaver’s neighborhood simply because a few neighbors object. (I’ve covered many planning board meetings in my day and that’s not an exaggeration.)

But we also need a change in our attitude that says buying anything other than a big, stand-alone house is a failure. After all, there’s plenty to not love about them.

Mandating a separation of uses not only creates sprawl, turning woodlands into cul-de-sacs, but it forces us to use our cars to do everything. That’s certainly the case for me: I’m not bicycling on narrow winding hilly roads, thank you very much, while it’s a 90-minute round trip walking to our general store and even longer to a grocery or hardware store. There’s no “live free” in transportation — driving is my only choice.

Suburban sprawl is also one of the driving forces (so to speak) behind America’s greenhouse gas emissions. If you give people walkable, bikeable, close-together spaces we will drive less and use less energy to heat and cool our smaller homes.

Sprawl is also lousy for building community. Two-acre zoning means houses are hidden away from the road, making casual encounters difficult. Again, look at me: I have met relatively few of my neighbors over the years and my kids had no nearby friends growing up; they had to be driven everywhere.

Another point made by supporters is that sprawl is expensive to taxpayers. It spreads out the need for public services — road paving and plowing, police and fire protection, school bus routes — without allowing more development that could help pay for it. No wonder my tax bill is so high!

Despite all the advantages to expanding options in our development patterns, I’m not terribly optimistic that it’s going to happen. This is one of those situations where local control often means local opposition to change.

But it’s worth a shot. Let’s make the middle a bit less missing, shall we?

Return to the Concord Monitor

Return to the Concord Monitor

I’m a long-time NH resident. This should be done, at least at the border with MA, in having a coherent policy between the two states. What will happen, will not be cheaper housing for NH residents so much as a push for MA residents to continue move to NH, keeping pricing high so long as there is a big differential in price between NH and MA. Note too, the farther north you go in NH, a relative decrease in housing prices (relatively of course, as housing is expensive everywhere). The problem with northern NH is distance and isolation from (non-telecommute) jobs, family, and services.

In Lyme, NH, our zoning is defacto 25 acre zoning (one home + one ADU) in most of the rural residential part of town (about 95% of town). Lyme may be extreme, but we are far from alone. Allowing the “Missing Middle’ in selected places, especially if mixed use is allowed, would help us welcome climate refugees and others who value NH living and allow creative sharing alternatives (like cohousing) while helping us protect what is important about living in small towns.