Last week’s news that the destruction of ash trees by an invasive beetle has driven a 168-year-old New Hampshire company to close was sad to hear, but since there are three different biocontrol species being released in the state, the problem will soon be fixed. Right?

Sorry, no. Not soon, probably not ever.

“Unfortunately, they’re not going to be able to save large, standing trees. Mature trees are pretty much all going to succumb to the ash borer,” said Bill Davidson, forest health specialist with the New Hampshire Division of Forests and Lands who is running the emerald ash borer biological control program here. “This is an attempt to keep ash around as a component of our forest, but it’s pretty much impossible that it will ever reach the status it currently has.”6% of our hardwood forests

Before the bright-green emerald ash borer came to the U.S. in the early 2000s, having hitchhiked in wooden crates carrying products from its home in east Asia, ash trees were a big part of woodlands in the East and Southwest. They made up an estimated 6 percent of New Hampshire’s hardwood forests.

The wood’s mix of strength, suppleness and looks led Major League Baseball to use it for their bats and also why Peterboro Basket Co. chose it for the the past 150 years to shave off strips of wood and weave them into high-end baskets.

EAB, as it is known by people tired of typing “emerald ash borer,” lays its eggs on ash trees. When larva hatch they drill into the tree and feed on the tissues under the bark that transport water and sugar, destroying the equivalent of its circulatory system. The result is almost always fatal to all species of ash in North America.

Tens of millions of ash trees have already succumbed to the EAB around the country – tens of thousands of them in New Hampshire including a couple on my property – and the infestation is still spreading. Partly as a result, Peterboro Basket Co. announced last week it would shut this summer after 168 years in business because it was getting harder to obtain ash wood.

Which brings us to biocontrol, which is everybody’s favorite idea for controlling invasive plants, bugs and animals. Use Nature to control Nature – what’s not to like?

Biocontrol is complicated

Almost as soon as the EAB problem was detected here, researchers went to east Asia, where the insect is native, and began hunting for predators that could be brought back. This sounds straightforward but it’s more difficult than I thought.

“In Eastern Asia it’s a pretty rare insect. Researchers have really had to work hard to find it,” Davidson said.

Determining what species prey on the beetle or larvae is also complicated. Then came the even harder job of raising enough to test whether they would survive here and, most importantly, determine that they won’t feed on any of our native insects. Biologists have gotten very cautious about biocontrol because history is full of cases where a would-be solution did more damage than the problem.

“It’s a rigorous screening process,” Davidson said. “ Even if it makes it through the screening process, it has to be able to be reared on a large scale. That’s another pretty challenging thing, developing methods to produce millions of them every year. Sometimes peculiar aspects of the biology makes that difficult.”

So far three species of wasp that lay their eggs on EAB at various points in its life cycle have been approved and are being released. One species lays its eggs onto the beetle’s eggs on the outside of tree bark, before they turn into tree-burrowing larvae, while the other two drill through the bark of the tree with their long, pointed ovipositor (Latin for “egg-laying stabbing thing,” I believe) and lay eggs on the larvae themselves. When the wasp eggs hatch they eat whatever they’re on, much to the dismay of the EAB.

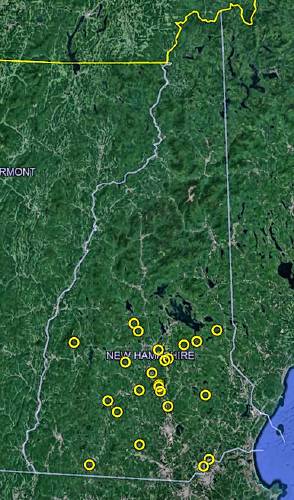

Populations of these wasps have been released at 22 locations around New Hampshire, with more being added. Repeat visits have confirmed populations thriving in at least 11 of those sites, and wasps have been found traveling at least five miles away.

So they’re becoming established in New Hampshire and are beginning to spread naturally through the forests. Why won’t this save our ash trees?

Its not bio-eradication

Part of the answer is in the word “biocontrol” – after all, it’s not “bio-eradication.” A constrained predator that won’t attack native species will never be able to wipe out an established invader; it would die out while hunting for the last few remnants. Remember, none of these predators have wiped out EAB in China. They just keep its numbers very low.

Then there’s timing. Even if these wasps spread throughout the continent and wreak havoc on the EAB – and it’s still not clear how much effect these wasps have on the beetle populations in North America – the beetle has too much of a head start. It will almost certainly kill all our mature ash trees.

If that’s the case, why bother at all?

“The goal is the aftermath forest,” said Davidson – meaning the forest where all the mature ash trees have died, leaving only seedlings and saplings too small for the beetle to complete its life cycle on. A few EABs will survive even then, because insects are incredibly hardy, ready to kill off any ash saplings that get too big. Those emerald ash borers are the future target of biocontrol.

“If (the wasps) get established, once we reach aftermath forests and the beetle population has crashed, then wasps will be able to make a meaningful amount of top-down pressure on the ash borer population, keeping it below a level where they’re causing tree mortality,” Davidson said. Then, perhaps the ash trees can start to return.

In the Midwest, where the beetle was first found, there are hints this is happening. But only hints.

“In Michigan and Ohio, already at aftermath stage, seeing pretty high rates of paratisastion by wasp species, above what’s required to keep ash trees alive,” said Davidson. “It’s too early to say. It will take multiple decades to play out.”

What should we expect? Davidson drew a comparison to the continent’s elm trees, a species that was far more prominent than ash trees, which was almost destroyed by Dutch elm disease between the 1920s and 1980s.

Young elms still sprout from root systems and live for a few years before succumbing to the fungal disease. A few naturally resistant elms have been found and are being used to try to establish new populations and variants have been cross-bed with resistant Chinese elms and are doing OK, although they don’t always look very elm-ish (I have a couple on my property).

But there’s no hope that the towering, vase-shaped American elm will once again become a big part of Eastern hardwood forests and provide shade on Elm Streets throughout the country. At best it can become a small part of the woodland ecosystem.

“The optimistic scenario (for ash) is something like elm,” said Davidson. “The super optimistic scenario, way down the line, might be better than that … but that’s super optimistic.”

That’s not exactly what I wanted to here, but its better than nothing. In a world increasingly filled with invasive species, that’s about as good as it gets.

Return to the Concord Monitor

Return to the Concord Monitor