Pretty much everybody who has ever driven in New Hampshire has accidentally hit and killed something at one time or another.

Usually, the casualty is a chipmunk or squirrel or frog, but more than 1,000 people face a bigger problem every year because they hit a deer. Then, there’s the 60 or so who have an even bigger problem because they hit a moose, which kills the humans almost as often as it kills the moose.

This is bad but hardly new — such multi-species carnage has existed since automobiles were created. Nonetheless, New Hampshire Department of Transportation, with help from university researchers, would like to do something about it.

There is, of course, a simple solution: Lower speed limits everywhere so we have time to react and avoid a collision. But Sammy Hagar’s “I Can’t Drive 55!” is the anthem of modern transportation planning, so that is never going to happen.

Years of study show that cheap, obvious acts do little. That includes putting up “Deer Crossing” or “Brake for Moose” signs and installing deer whistles on your car. Those whistles are passive air horns which make a noise as wind passes through them designed to scare off animals, but alas, no such luck.

Building wildlife bridges over a highway do work, as has been demonstrated out west, but they cost millions, so that’s not going to happen here in New Hampshire.

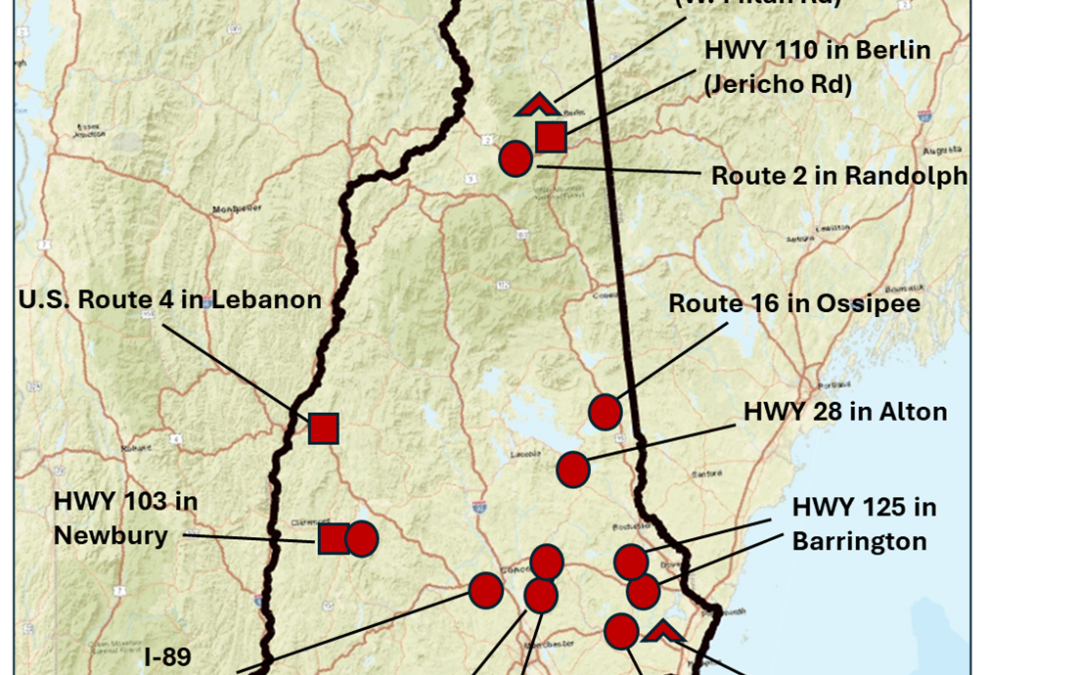

As part of a DOT program to see what, if anything, we can do, Prof. Amy Villamagna of Plymouth State has identified places where the most animal-vehicle collisions happen. These are places where lots of animals move through and where lots of cars travel, making it hard to see what’s coming up. One of the “hot spots” is near the I-89 and I-93 interchange in Concord.

At UNH, Prof. Rem Moll is taking the next step by getting the information needed to tackle the problem: “We’ve analyzed the places that they’re happening [and are asking] ‘why? What’s driving it?’”

His research found that hot spots tend to exist at wildlife corridor bottlenecks: places where development has fragmented local wild areas, leaving animals with few options when going from one side of the highway to another. Surprisingly, too much fragmentation reduces collisions, perhaps because the local animal population gives up moving.

This knowledge can at least help planners anticipate how future development might increase or decrease the problem of vehicle-animal collisions.

His research has also reached one unfortunate conclusion: The cheapest way to help animals cross the road safely doesn’t work very well. Those are culverts, the pipes that carry streams or runoff underneath roads.

Culverts are an obvious travel route for wildlife, but game cameras watching them at hot spots showed “there were a lot of animals on the roadside that are not using the crossings, not going underneath the road,” Moll said. In particular, “we didn’t record a single deer using any of the culvert crossings,” not even culverts that are more than 5 feet tall.

Some redesign might help, such as installing a “critter shelf” so small animals can cross through without getting their feet wet, but it looks like culverts won’t solve the deer and moose problem.

The one thing that does work with big animals, Moll said, is putting up roadside fences at hot spots to shift road crossing to less-dangerous locations. Unfortunately deer fencing, which has to be at least 8 feet tall, is expensive to build and maintain. Still, it’s feasible.

At the very least, Moll said, research can help DOT decide whether, where and when to built these fences.

“That’s what this project is trying to do for DOT, to get them a priority… If you were to put limited resources into a change, here is where you think you could get the most value,” Moll said.

In the meantime, slow down. The life you save, as the public-service announcement goes, might be your own, but you also might save your neighborhood Bambi.

Return to the Concord Monitor

Return to the Concord Monitor