You will be glad to hear that I have figured out a sure-fire retirement scheme once I’m no longer getting the huge paychecks handed out to newspaper reporters: Breeding praying mantises!

No, wait, hear me out.

Aside from being the coolest insect (dragonfly aficionados may object), praying mantises are voracious predators of anything that moves. And that, I’m happy to say, includes the spotted lanternfly: videos exist online of mantises happily chomping away on this latest Scary Invasive Insect.

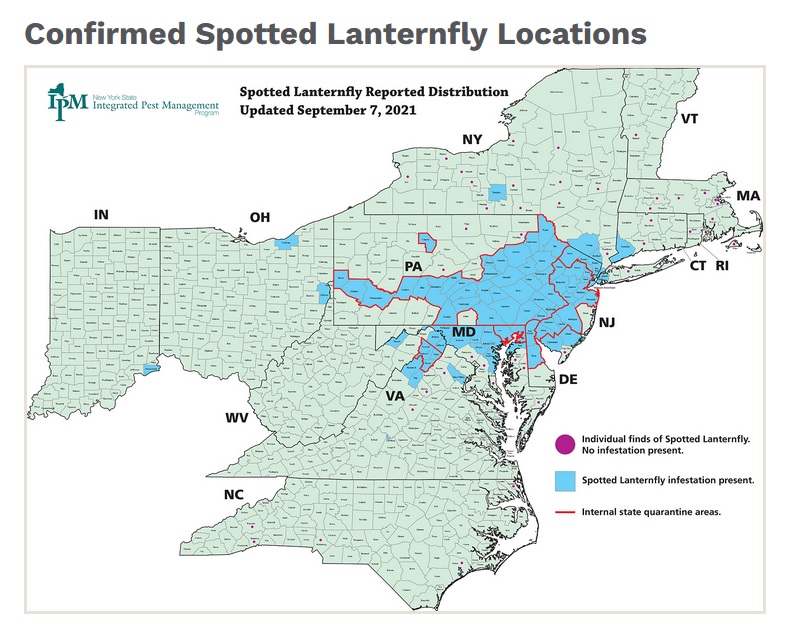

You probably don’t know the spotted lanternfly, but you will. First seen in the U.S. in southern Pennsylvania in 2014 after apparently arriving as egg masses on a shipment of stone from east Asia, it has established itself in six states, including southern Connecticut.

A few individuals have been found in Massachusetts, apparently carried there on trees or plants shipped into the state, and the New Hampshire Department of Agriculture is asking people to keep an eye out for it.

Interestingly they’re also asking you to keep an eye out for an invasive tree that is called the Tree of Heaven because it grows very quickly, not because it’s angelic. This tree, only a minor problem in New Hampshire because we’re at its northern range, is a preferred host of the lanternfly. This is a classic case of invasive species compounding each other: If we had killed off the Tree of Heaven there’s a chance the lanternfly wouldn’t have gotten established.

The climate emergency is a factor, too. New Hampshire’s winters used to keep a lot of bugs and plants from getting established, but our natural seasonal defense is fading away as temperatures rise.

This is bad news because the world is awash in invasive species that have thrived when removed from the ecological balance of their home range and have overwhelmed local species. Insects, aquatic plants, mammals, birds, fish, land plants – you name it; they come here from Asia or Europe or South America and do damage, and ours go there and do just as much damage.

We’re going to keep hearing about them as long as humans keep moving around the globe.

The spotted lanternfly has the benefit of being beautiful in its adult form, with a red body and black-and-white spotted wings. But it has the drawback of feeding on lots of different plants (grapes in particular – vineyards are worried) and, like all invasive bugs, facing few predators or diseases here.

When it gets established, it’s not uncommon for entire tree trunks to get covered with such a seething mass of the insects that you can’t see the bark. It’s kind of gross.

Such scenes have led Philadelphians, an early hotbed of the invasion, to join the anti-lanternfly bandwagon with the enthusiasm they usually reserve for booing Santa Claus at football games. One family, for example, has created an app called Squishr that lets people record how many lanternflies they’ve killed, with extra credit for uploading a photo of the squished bug. As of the moment, the top score is 1,023.

As reported by Philly Voice, a local alternative paper, there are “Spotted Lanternfly Ninja” T-shirts, a song called “Die, die, die, spotted lanternfly” recorded by a local band and, as you might expect, bugcrushing-inspired drinking games at local bars.

That’s all well and good but I can’t imagine this kind of response will make any real dent in the invasion. Insect reproduction is orders of magnitude faster than any physical action that people can take.

It will require biological and chemical response to slow the spread and perhaps contain it. Hence my Granite State Mantis Production proposal. If nothing else, it will be a lot of fun.

As soon as I launch my Kickstarter fundraising, I’ll let you know.

In the meantime, if you see a spotted lanternfly you should let the state know: “Photos are good, specimens are better,” says the website, www.agriculture.nh.gov/divisions/plant-industry/spotted-lanternfly.htm

Return to the Concord Monitor

Return to the Concord Monitor

Dear Mr. Brooks,

I am doubtful that praying mantises will eat very many, if any, of the spotted lantern flies– but in the name of science, it is certainly worth testing.

Also, you mention the spotted lantern flies’ egg masses. So, would it be possible to find and destroy them as a way of eliminating vast numbers of the insects?

This is a test reply to Garth’s comment.