We all know that offshore wind power has been very slow in coming to the U.S. but compared to offshore water power it is moving at lightning speed. At UNH they’ve been pondering this imbalance for a while.

“Twelve, 13 years we were saying we are about 20 years behind wind. … Now we’re 26 years behind wind,” is how Martin Wosnik puts it, only slightly joking.

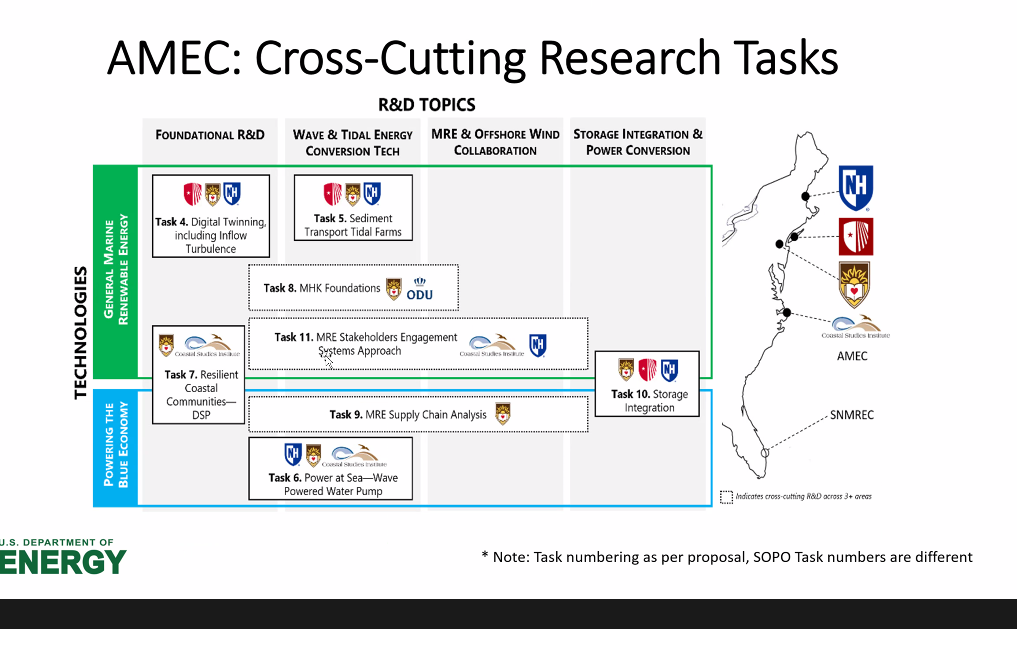

UNH has had a Center for Ocean Renewable Energy for a decade, but things are starting to pick up. Wosnik, an associate professor of mechanical engineering at UNH, has just been named director and principal investigator of the new Atlantic Marine Energy Center (AMEC), a multi-site consortium involving universities and national labs around the East Coast that will be led by UNH.

AMEC received $9.7 million over four years from the U.S. Department of Energy to support research and testing to finally move wave power and tidal power from potential to reality.

It seems a little weird that such basic help is needed. The world has hundreds of enormous windmills sitting in oceans all over the place that use moving air to spin turbines, but virtually nothing under the surface that uses water to spin turbines. Since water is about 800 times denser than air, it could produce vastly more electricity from the same spinning blades — what’s the holdup?

Maintenance, mostly. Seawater is corrosive to most metals and other materials, and the constant battering of waves or tides is brutal on machinery. Plenty of pilot projects have been launched by researchers and start-ups but most ran out of money trying to keep things working before they got too far along.

As a result, Wosnik said, some really basic questions have not been answered about the best way to produce electricity from moving seawater.

“The technologies haven’t really converged in either tidal or wave energy” he said, pointing to wind power for contrast.

“In wind, no matter who you buy a turbine from, it’s a pitch control, upwind, three-bladed rotor on a stick.” Decades of research and development have shown that this configuration creates the best mix of output, cost and reliability.

By contrast, underwater “we don’t even know whether axial flow or cross-flow turbine is the best” he lamented – meaning it’s not clear whether water should flow along the axis of a spinning turbine or perpendicular to it, which is about as basic a piece of design information as you can get.

AMEX has two main goals, Wosnik said: To help others develop devices create energy for the grid from the power of waves or the tide, and to help the development of smaller devices to power the “blue economy,” a term for industries on the ocean where it’s impractical to run a long extension cord to shore.

“An example might be an offshore kelp farm and you need to have some on-site power from what’s available in the ocean,” Wosnik said.

“We are not technology developers, although we may develop some components. We are looking to facilitate what industry needs to do in this space – we are really supporting industry,” he said.

UNH won the bid to run AMEC partly because it already has some good sites for testing devices at the 2- to 3-meter scale, which is big enough to answer important questions, Wosnik said. That includes wave tanks (think swimming pools with some funky equipment) in the Chase Ocean Engineering Laboratory and, more unusually, the Living Bridge floating lab underneath Memorial Bridge, where scaled models can be tested as tidal waters race into and out of Portsmouth Harbor.

“Just building it was a learning experience. You don’t usually build a floating dock in 6 knots of current,” Wosnik said of the Living Bridge.

AMEC can be thought of as a collaborative organization. It will hire some postdocs and grad students but won’t have a building of its own. Other institutions part of AMEC are Stony Brook University, Lehigh University and the Coastal Studies Institute of East Carolina University, as well as four national labs on the east and west coast. It will probably also do some testing at the European Marine Energy Center around the Orkney Islands off Scotland, taking advantage of Europe’s lead in the area, and work with the Shoals Marine Lab on Appledore Island to see if marine energy can be incorporated into its island microgrid.

Of course, $9.7 million spread over four years and at least four institutions isn’t a huge amount of money when you’re talking about developing new technologies, but the hope is that AMEC will provide a focus for a lot more research, and research grants.

“It’s a very positive thing to have a center like this on the East Coast. It has been a long time coming,” Wosnik said.

Return to the Concord Monitor

Return to the Concord Monitor