Next time you’re filling up your car and moaning about the cost, imagine if the price of gas went down at midnight and you could fill up at night without leaving the house.

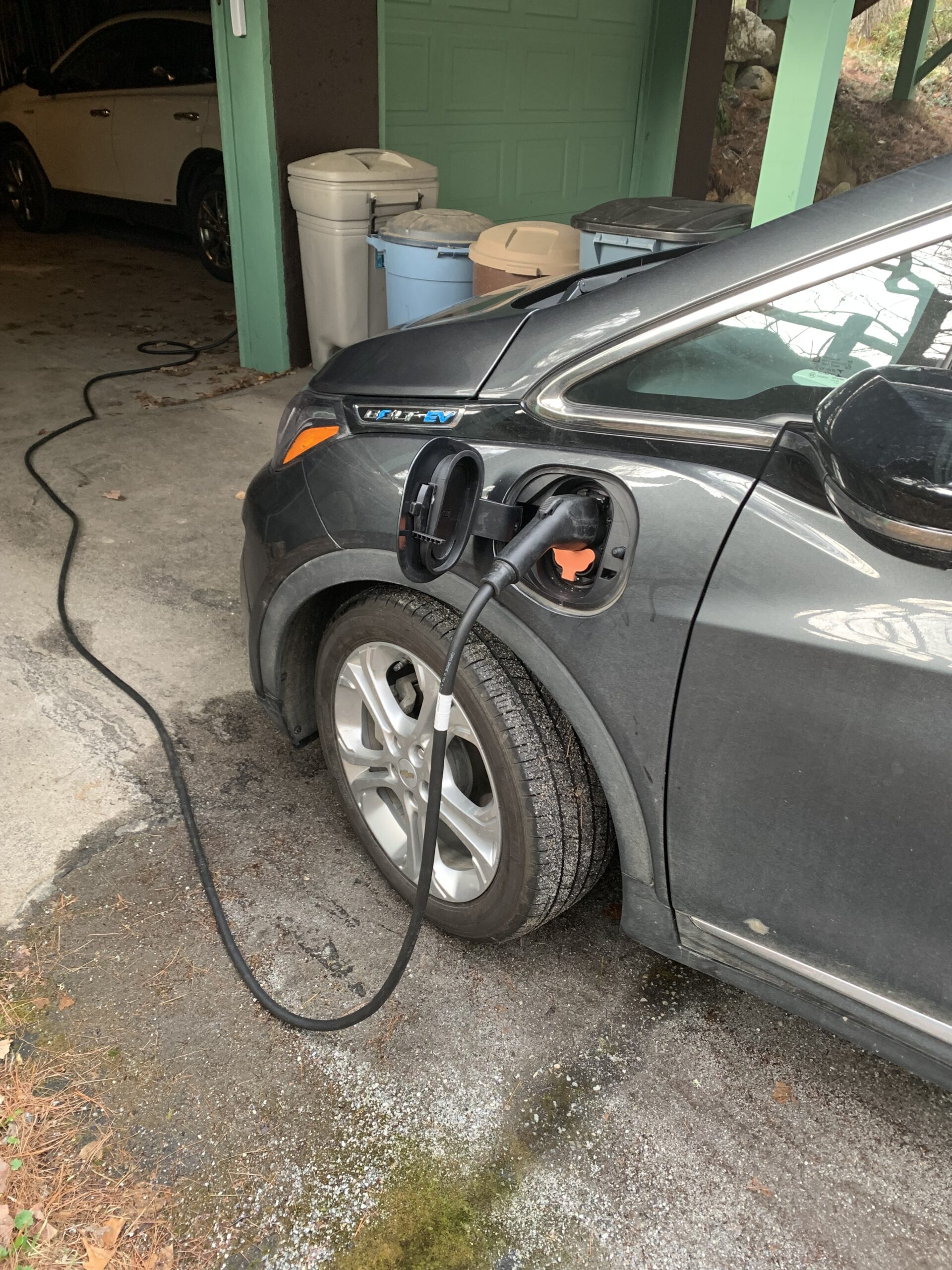

Replace “gas” with “electricity” and that’s smart charging.

Better yet, imagine if you could fill up cheaply at midnight and then sell some of the gas back to your service station when the price was high again, making a buck or two and reducing the amount of extra fuel brought in to serve afternoon commuters – also without leaving the house.

That’s vehicle-to-grid, potentially the most revolutionary effect that will come from switching internal-combustion cars and trucks to electric.

V2G, as it’s known, allows big expensive objects that have the single function of transportation to take on an entirely new function of energy storage. By absorbing and releasing electricity via V2G, cars and trucks can ease the strain on our power grids and reduce the numbers of new transmission towers and wires and substations we have to pay for as our energy system transforms.

Although the idea for V2G has been percolating for decades it is only just starting to take off in the U.S. (Europe, as is usual with transportation, is way ahead of us). The federal government is collaborating with car companies, tech firms and unions to speed up understanding and adoption of V2G, focusing on California because that’s where the most electric vehicles exist. Electric vehicles are starting to be sold ready to send power back into the grid as their manufacturers realize this is an extra selling point.

If vehicle-to-grid is so awesome, why aren’t we seeing it already? We’ve certainly known its value for a long time.

“I wrote a paper on vehicle-to-grid in the late 1990s,” said Steve Letendre, regional director of Regulatory and Government Affairs for Nuvve, which makes V2G software.

The problem, he said, is that all the components haven’t come together until recently. That includes electric vehicles and “smart” system software, but also regulatory changes allowing electric utilities to charge different rates at different times and for different uses.

“It’s a common theme that innovation in and of itself isn’t enough. Conditions have to be right where innovation is adopted and deployed at scale,” Letendre said. “I think we’re at that tipping point, with things starting to come together – auto manufacturers are aware, utilities are aware … there are starting to be compatible devices that will talk to each other.”

So far as I know, the only V2G in New Hampshire is a small pilot project getting underway at Plymouth State University.

It will involve two Nissan Leaf electric cars that will use Nuvve software and hardware from a company called Fermata to charge when the price for electricity is cheap and discharge back into the grid when the price is high, minus the amount of power that’s used when they are driven around.

Electricity resale will help cover PSU’s costs but, more importantly, New Hampshire Electric Cooperative will get experience working with V2G so it can decide how much of a factor it should be in planning. NHEC is the obvious target for the study because as a cooperative, it has more flexibility than utilities regulated by New Hampshire’s not-terribly-forward-thinking Public Utilities Commission.

You can learn more when Letendre is one of the speakers at the Energy Innovation Conference at the Derryfield School in Manchester on May 24, sponsored by Clean Energy New Hampshire.

Nuvve is concentrating on electric school buses, Letendre said. With their large batteries and predictable schedule, including little use in summer when electricity demand is high, they are a perfect V2G platform. Among other things, school districts could profit from the electricity sales to help make up for the higher purchase price of buses that don’t spew diesel fumes around kids in the elementary school parking lot.

N.H. Electric Cooperative is looking for a school district or bus company in its service area to run a V2G school bus pilot project.

In the meantime, those of us trundling around in behind-the-times vehicles powered by loud, inefficient explosions of fuel-and-air mixtures that can’t be refueled at our homes are watching wistfully and dreaming what might be.

Return to the Concord Monitor

Return to the Concord Monitor