In their 156 years of climbing to the summit of Mount Washington, the Cog Railway locomotives have gone from burning wood to burning coal to burning oil to burning diesel to burning biodiesel. If all goes well, in July a prototype will make the climb while burning nothing at all.

“In 2008 we switched to diesel, going from the 19th to the 20th century. But now we’re in the 21st century,” said Caleb Gross, the mechanical engineer for the Mount Washington Cog Railway who is leading the effort to create its railway’s first battery-operated train.

Gross said the project dates back to brain-storming in 2022 – “Wayne (Presby), our owner, he’s all about electric drive; he owns a Tesla” – and took fire after it included the railway’s ongoing partnership with UNH. Five seniors in the mechanical engineering department are now working on the electrification project along with Gross.

Running the Cog with electric motors makes sense because batteries can use regenerative breaks to recoup much of the power when crawling back down the mountain. With grades of up to 37%, this is the second-steepest cog railway in the world. But theory and practice don’t always coincide, especially for a one-of-a-kind operation like the Cog Railway that has to design and build virtually everything in-house.

The original plan was to electrify the “speeder,” a smaller, faster engine that the Cog has long used to rush up the line to do things like carry out injured hikers, bring material up to the Observatory at the summit or help stalled engines. Depending on how that went, the Cog would then consider electrifying some locomotives. But dimensional limits squelched that idea.

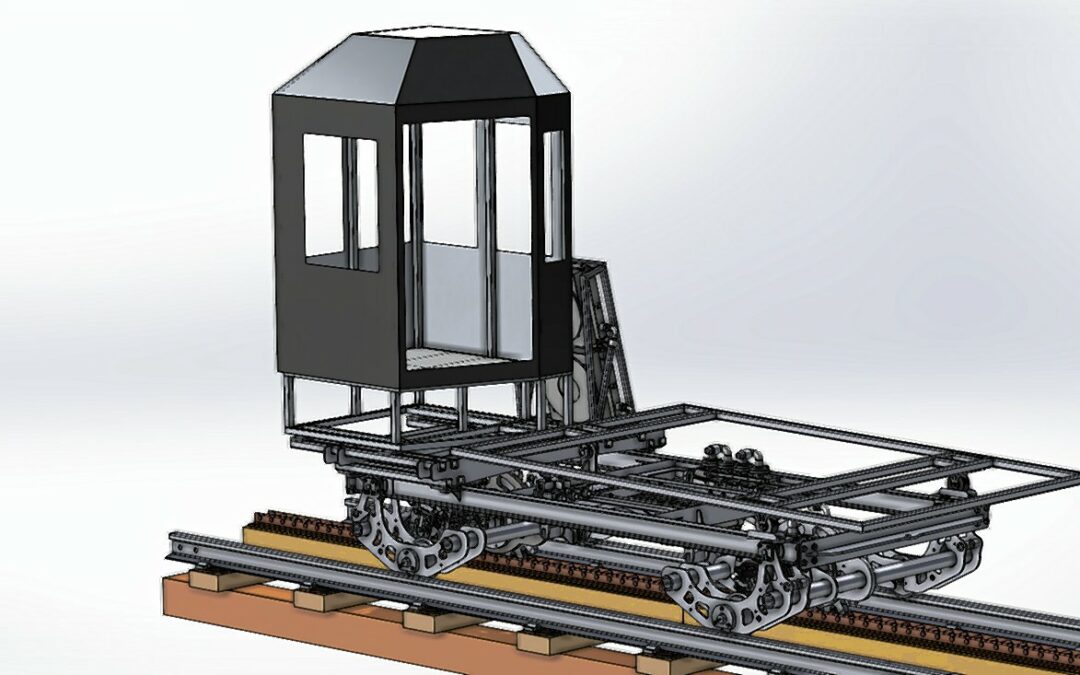

“The motor needs to be this big, the battery pack this big – it won’t fit on the (speeder),” said Gross. “Eventually we decided to make an entirely new vehicle. It’s a lot easier to design from a new platform.”

The new platform has a wheelbase of 8 feet, compared to 12 feet for the passenger-hauling locomotives, and is designed to make it from bottom to top in 15 minutes, compared to 37 for the current Cog. There’s no trouble getting an electric motor to do that; the big issue, the one that faces most attempts to electrify transportation, is charging. Turnaround time at the Marshfield Base Station is fairly short and it’s a challenge to refill the batteries in time.

“The capability of the battery cells themselves to be able to take in the charge, that’s what we’re looking at,” said Gross.

Gross said they’re leaning toward a custom-built pack with a 31.87 kilowatt-hour capacity to be able to make the two trips at nominal vehicle weight. “We may play around with this a little as development progresses, but this will consist of 2,730 standard Li-ion cells configured arranged together in a liquid cooled, highly monitored pack,” he wrote in an email, adding that “also waiting a while until we’re ready to have it built in case some new technology comes around.”

These are the sort of new issues that make the project appealing, says TatumVansicklen, one of the UNH students who has been hands-on in the Cog shop. “Innovation is what works for me – the first in the world to do this, that’s what caught my attention. … All our friends and family, they think it’s crazy, creating the first vehicle to ever be able to do this kind of thing.”

“There is a coolness factor that definitely comes into play, working with the Cog,” said fellow student Will Callery. Also part of the project are students Nathan Facteau, Alex Mills and Joseph Bailey.

“They’ve really got a lot of experience out of this,” said Gross. “I’ll say: I need a bearing that’s 14.24127 inches in diameter. You have one that’s 14 and one that’s 15 – how do we adapt, make this component work for it?”

He compared it to many engineering projects. “Often times you’re working with one little screw – you don’t see the bracket attaching it to the wall; and can the wall handle that? This is not just working with software designing, or a bit of construction; it’s the entire project.”

The Cog Railway is paying for the project, which has a budget of around a quarter-million dollars, Gross said. The goal is to create an electric multipurpose vehicle that has modular components that can be swapped out. “We want a flatbed, a service body, a rescue/ambulance superstructure with litter and first aid supplies, as well as a passenger cabin,” he said.

The original plan was to have a full prototype to climb to the summit this summer but problems including lingering supply-chain issues have pushed back what was always an ambitious timeline. Now the goal is to have a self-propelled unit that demonstrates feasibility.

If that works, it will go on to be a model for electrifying locomotives and removing a small but high-profile source of pollution from the White Mountains and getting the state’s most unusual public transportation system ready for the new reality.

“I’ve always really liked diesel engines, the sound of them, but looking where everything is going it’s pretty mandatory to learn at least the basis of how electric vehicles work … and to be able to apply it,” said Callery. “Because this is just the first step to where the world is going to be going for battery-powered vehicles.”

Return to the Concord Monitor

Return to the Concord Monitor