NOTE: If you subscribe to my newsletter, you saw this last week. So why not subscribe – right here!

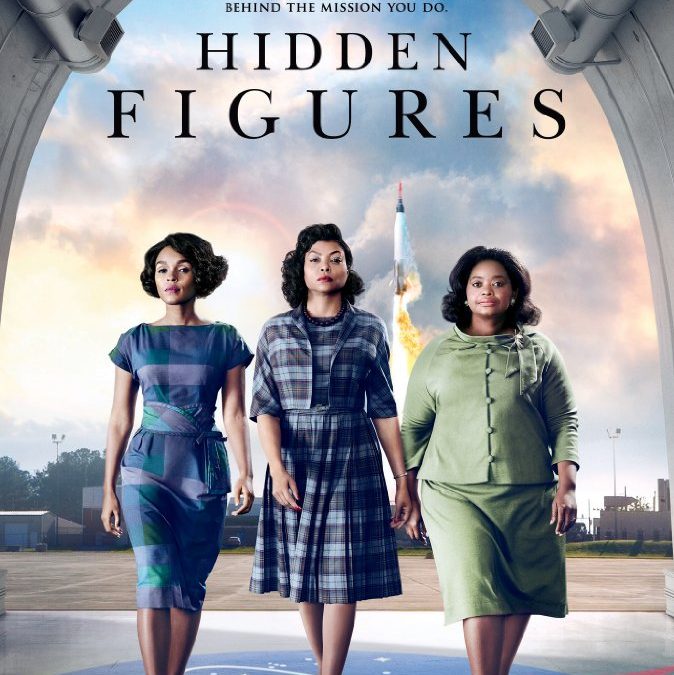

I recently saw “Hidden Figures,” the movie about the black women “computers” who helped the early NASA manned launches, and it was great. Anybody who reads this newsletter would enjoy it, I think. (I saw it at Peterborough Community Theater, which was just put up for sale: Anybody out there want to be a movie mogul?)

The movie was great for many reasons, but I liked it most because the heroes were unusually good at math and yet were normal people!

Usually math brains are depicted in movies as borderline crazy (“A Beautiful Mind”) or weirdly anti-social (“The Man Who Knew Infinity”) or unpleasantly dorky (too many to mention). The assumption is that deep interest in mathematics is not something normal people have.

Mathematics is is only embraced in movies by people you don’t want to be like.

But the three women at the center of “Hidden Figures” have ordinary personalities and looks (they’re better looking than us but only one of them is ridiculously gorgeous, which is pretty realistic for Hollywood). They have ordinary families and relationships. Enjoying and understanding math is just part of their life, like enjoying clothes and understanding how to drive. (I liked the opening scene that showed a little girl counting her steps, saying “prime” whenever she got to a non-composite number.) What a pleasant change.

There is almost no actual mathematics in “Hidden Figures,” of course, but what’s there is pretty accurate. Euler’s method, as a way of calculating rates of change through incremental steps instead of a single formula, would work to move from elliptical to parabolic orbits as depicted and it was used at least in part. The quick talk about how orbits work is really good, too.

And you have to love those awesome enormous blackboards, so big that you needed rolling ladders to reach the top. They were real.

Of course, also real was the racial prejudice and gender put-downs that the women constantly faced. These were depicted in a restrained yet powerful way, with most whites depicted not as evil racists but as unconscious racists, vaguely well-meaning but blind to reality. This came across best in the way the central character had to walk a half-mile outdoors to go to the bathroom because her building had no “colored” restrooms, something her white colleagues hadn’t even realized.

One last and not very happy point: Part of the pleasure of watching movies about the Civil Rights era is mentally associating with the heroes, the people who pushed back against Jim Crow and segregation laws. It gives us a warm, happy feeling to see them succeed and think how they would have thanked us when we helped them.

The way things are going, we’ll soon have a chance to translate that fantasy into reality. Will we?

Will you and I really push back if prejudice becomes government-sanctioned? I hope so, but it’s going to be a lot less easy and fun than it seems like it would be while we’re sitting in a movie theater.

Boy, I’d much rather think about math.

Return to the Concord Monitor

Return to the Concord Monitor