This is one of two stories in today’s Concord Monitor that are part of my search for the oldest operating solar panels in New Hampshire. The other story is here.

There’s a warm, fuzzy feeling that schools get when they put solar panels on the roof, becoming all high-tech and environmental at the same time.

Just ask Hopkinton Middle High School; it has been basking in that feeling for a little while. Actually, make that a long while.

“It came from a grant that I wrote when I was teaching there. Bill Clinton had a program going: a million solar roofs. It was an extension of that,” said Will Renauld, who now teaches engineering at St. Paul’s School.

Wait – Bill Clinton? You mean the president before the president before the president before the current president?

Exactly. The 16 solar panels on the roof above the art room at Hopkinton Middle High School were installed in 1999, a full 18 years ago. That makes them, so far as I can tell, the oldest operating solar panels on any school in New Hampshire.

Operating is a relative word, however. Hopkinton’s system had an original maximum output of 2 kilowatts – 2,000 watts – but when I visited last week it was producing only 10 percent of that, about 200 watts.

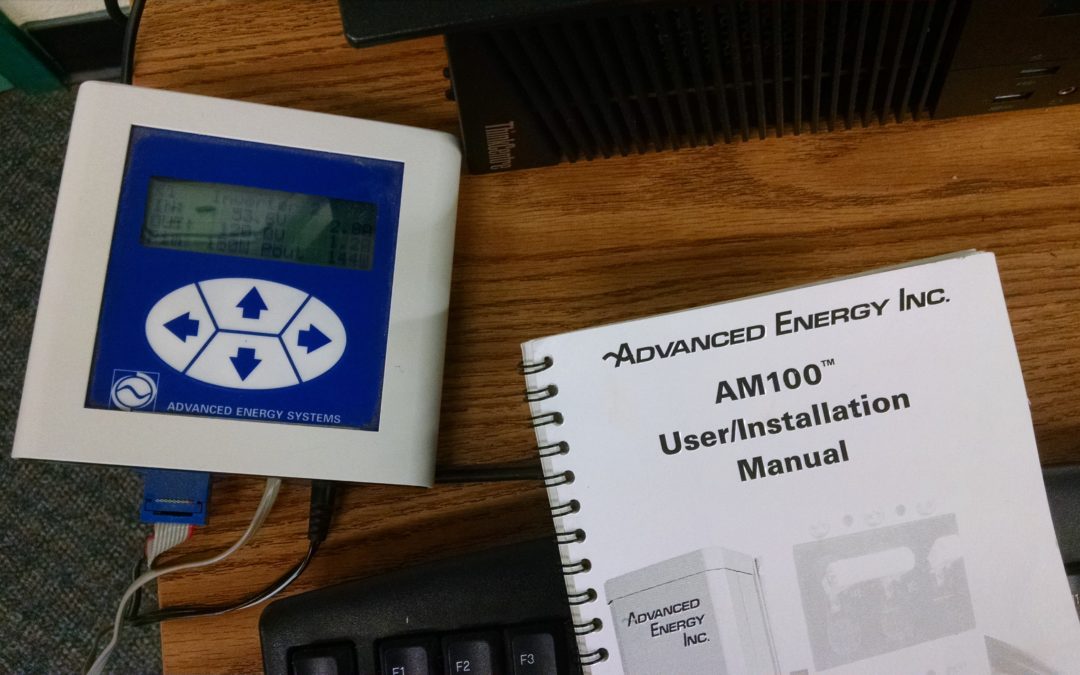

The inverters (the one on the left doesn’t work) behind the controls for the Hopkinton School solar system, which runs on DOS.

The panels themselves didn’t seem to be the problem. They looked in pretty good shape except for few small blotches on the glass. Panels do slowly degrade over time, but not usually to such an extent.

Hopkinton’s shortfall had other reasons. The sun was feeble the day I was there and, more importantly, a couple of oak trees have grown up in the decades since installation to partly shade the array.

“This probably was a prime spot in 1999 before those trees grew up,” said Bill Caruso, the district’s facilities director, who led us up on the roof to see the array.

Caruso is a fan of the system, which requires virtually no effort on his part, partly because of the design.

The array is held down by about 300 pounds of cinderblocks under each set of panels rather than with bolts, much to Caruso’s approval: “Anytime you can not penetrate the roof, that’s good.”

The system is connected by one wire inside conduit, which runs over the roof and down to the school’s Computer Aided Design/Drafting classroom. That’s pretty much it on the roof.

Down in that classroom, another problem lurks. One of the two inverters – which change the panel’s DC power into the AC power usable by the school – has failed, a fact discovered by 10th-grader Connor Blais, who is two years younger than the equipment he was analyzing.

“(Pre-engineering teacher) Mr. Christie said ‘I have a project for you – do you want to see if the solar panels are working?’ ” said Blais, removing the inverter’s cover to demonstrate the problem.

The school didn’t realize the inverter had failed because the array is pretty much ignored unless it’s being used for a classroom exercise.

This is a compliment by the way. These panels have been working on their own all these years, cutting the school’s electricity bill by a small amount with no cost for fuel and virtually no maintenance. Not bad.

Another reason it’s hard to keep track of what the array is doing: The New Hampshire company that built the system went out of business in 2001 and no other company ever took over its customer list. So there haven’t been any service contract or system upgrades in decades.

The control system still uses DOS, the pre-Windows operating system from Microsoft. The instruction manual – amazingly, the school hasn’t lost the operating manual in 18 years! – tells you how to run everything via a dial-up modem and notes helpfully that the operating system can be loaded via floppy disks.

Moving a DOS system from computer to computer over the years is hard, so most of the history of the panels’ production has been lost.

Matthew Stone, the district’s director of technology, hunted through old computer files and found a record from November 2007, when the panels were generating about 1,200 kilowatts at peak. That’s about 60 percent of the maximum, which isn’t bad for then-eight-year-old panels dealing with the early-wintertime sun.

The lack of long-term records, however, means we can’t say how much electricity has been produced and how much money has been saved on the district’s power bill. The array, Renault said, cost about $30,000, of which the school district paid 10 percent, or $3,000. With such a small system operating in less-than-ideal conditions, the smart money says that if there’s any profit from deferred electricity payments, it’s pretty small.

But the environmental benefit of local solar power is still real, and who knows how many students have been inspired by the panels?

The community of Hopkinton is still embracing solar power. The town fire station recently installed a 58-kilowatt system – 29 times the output of the school’s array.

Other schools like solar, too. According to a database from a group called Generation180.org, at least 19 schools in New Hampshire have solar panels installed on their property to the tune of 941 kilowatts, which is almost 50 kilowatts per school.

Not bad. The Hawks at Hopkinton say welcome to the club.

Return to the Concord Monitor

Return to the Concord Monitor

Hi David, I heard the story about this on NHPR yesterday. Thanks for your interest. When this system was installed I had just started working for Solar Works who installed this system at Hopkinton. I was responsible for this and many other school installs in NH, we did over a dozen. I’m still in the solar business and own New England Commercial Solar Services and have just launched a Solar On Schools program. I would love to discuss this with you at some time.