If I was going to redesign the national power grid, perhaps the biggest and most complicated thing that the human species has ever created, I wouldn’t think of starting in a quiet part of coastal Maine.

But maybe I should.

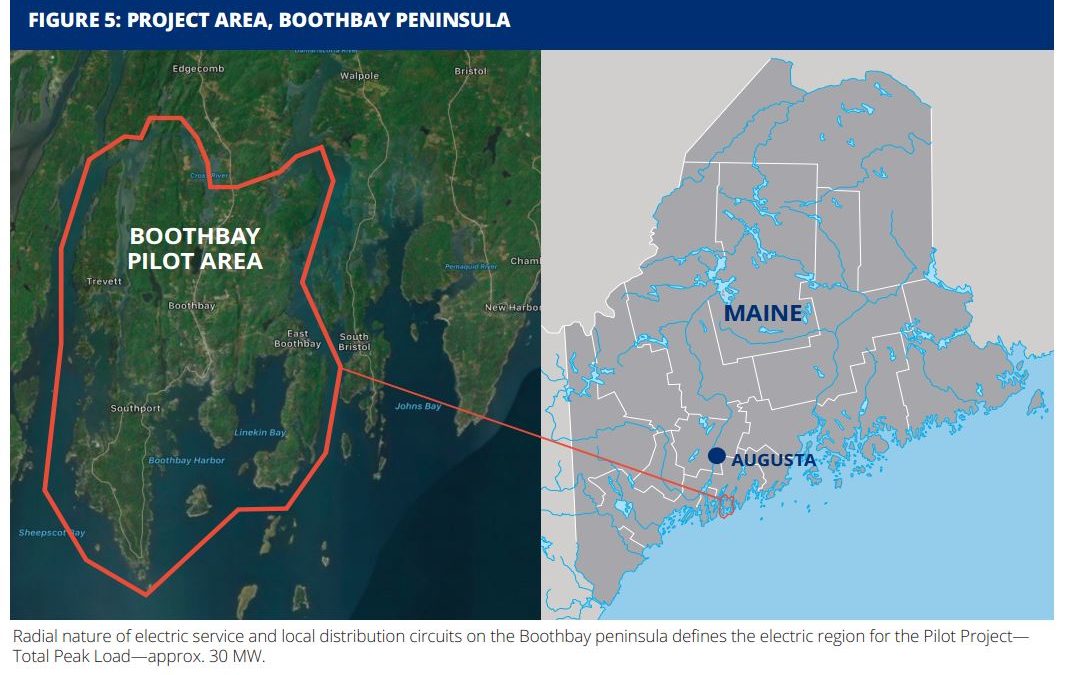

“We figured if we could do this in Boothbay, we could do this anywhere,” said Rick Silkman, an economist and energy consultant who co-founded a company called GridSolar.

That solar-energy firm collaborated over the past several years with Central Maine Power, the state’s biggest utility, on an interesting project to see if distributed energy and intelligent efficiency could take the place of new, expensive power lines – a process known in the industry as a “non-wires alternative.”

“This was our first non-wires alternatives project,” said Mike DeAngleo, a program manager for such programs for Avangrid, which owns Central Maine Power. “What we’ve learned as a company we’re using elsewhere.”

After much debate, CMP instead went with a pilot project that used solar panels, more efficient lighting, a power-storage system that froze and melted ice on demand, plus a couple of (ugh) diesel generators, all of this controlled in concert with the utility’s needs and predictions of need.

“From an electric system perspective, it was a good place for a pilot because it was simple. If we had tried in Portland, an urban area (with) a very complex system transmission and networks, it gets a lot more complicated. Boothbay was one transmission in and a couple of substations,” said DeAngleo.

Saved $6 million

So how did it go? In a way, great: Over two summers, it did everything that was needed at a cost of $6 million.

Saving $12 million bucks – not bad! And it gets better.

It turns out that the projected increase in Boothbay’s power needs didn’t happen for a variety of reasons. If CMP had built its transmission line then all those expensive cables and towers would have been largely superfluous. But the generators and thermal-storage systems in the pilot project are being moved to where they will be useful, while efficiency improvements and solar panels will continue to produce savings, regardless.

Silkman of GridSolar points to this as an example of flexibility that is one of the major benefits of doing things in the non-traditional way.

“There are two lessons,” said Silkman. “The first is that in certain instances, by siting generation at the distribution level on the grid you can avoid transmission upgrades … The second aspect that was demonstrated is the ability to incrementally deal with growth.”

You can install storage and panels and efficiency systems pretty quickly, and then quickly add more if needed. Not so if you’re building new towers and transmission lines.

“With a wire solution, it’s all or nothing,” said Silkman. “You get this enormous increase in capacity, and for 90 percent of time you don’t need it.”

The tyranny of ‘peak demand’

That’s an important point. Because it’s very hard to store electricity, a big chunk of the gazillions of dollars spent on towers, poles, wires and substations goes to meet “peak demand,” the maximum amount of electricity that will be needed at any one time – usually during a hot afternoon in August when air conditions are going crazy. When it’s not peak, those systems are superfluous.

“You get this enormous increase in capacity, and 90 percent of time you don’t need it,” said Silkman.

You can save a bunch of money if you can meet this occasional need in other ways, such as by storing electricity in batteries or ice-making machines during non-peak times and using it at peak, or by paying customers to reduce their electricity usage when needed, which is known as demand response. This is the best economic argument for non-wires alternatives.

The other argument is environmental: Generally, non-wires alternatives produce less pollution than wires alternatives that depend on large power plants.

The Boothbay pilot can’t be considered a complete success, however. Partly that’s because it was so small – 1.85 megawatts, with no commercial or industrial component – that its lessons are a bit limited.

But the big problem was the lack of anticipated growth in electricity demand. This prevented the pilot from being tested at its limit. GridSolar had to pretend that load growth increased in order to test the system.

As you’d expect, the project found some technical and organizational issues, which is the point of running a pilot in the first place. But in general, it demonstrated how these new systems are a snap to use.

“Batteries are a great resource. I can see why utilities like them,” said Silkman. “You literally turn it on and dial it in. We were running them from offices in Portland.”

One time, he said, CMP said they needed the batteries turned on when the dispatcher in charge was at a softball game. “He took out his phone, turned the units on, and stayed at the game,” Silkman said.

Great, yes, but from GridSolar’s point of view, it also demonstrated a stumbling block in designing and applying new types of systems.

Little incentive to change

“The problem is that there’s no advocate for non-wires alternatives, no entity that has a level of expertise that a utility does in looking at these broader solutions,” he said.

Power utilities have a century of experience calculating how much to build to optimize the one-way power grid, but almost no experience in calculating alternatives. Further, they have little financial incentive to change.

Utilities make most of their money by getting reimbursed for building power infrastructure. Nobody has quite figured out how to pay them for helping to reduce the need for electricity.

“Utilities have no skin in the game. Our experience is that they don’t do as careful analysis, as tailored an analysis, as they might otherwise do,” Silkman said.

Silkman said that while non-wires alternatives are becoming less uncommon – he pointed to the island of Nantucket, where National Grid may undergo a similar storage-and-load-management pilot – most projects are overseen by the power utilities, who don’t have incentive to disrupt the existing system.

He gave this parallel: “You can imagine the automobile that the railroad companies would have designed if they were developing alternatives to railroads.”

For its part, Central Maine Power is more upbeat about the Boothbay pilot.

Avangrid, CMP’s parent, has a major presence in New York, which under the Reforming Energy Vision or REV program, is shaking up the whole power system. DeAngelo says the lessons from Boothbay – some as simple as making sure the refilling schedule for diesel generators doesn’t interfere with power production, others as complex as verifying the effect of energy efficiency on peak loads – are being applied as Avangrid works to meet New York’s goals.

In particular, he said, lessons learned from Boothbay are helping Avangrid develop a series of criteria to measure how suitable non-wires alternatives can be in any given situation.

“It will integrated into our utility planning so when they look at developing a project to address a system need, they’ll apply a suitability criteria to see if it applies,” DeAngelo said.

That sounds pretty boring and bureaucratic, but it’s exactly the kind of process that needs to happen if we’re going to bring electricity production into the 21st century.

Return to the Concord Monitor

Return to the Concord Monitor