This is an edited report from Atlantic Salmon Federation, with my addition in bold: The number of North American wild Atlantic salmon dropped 15 per cent in 2017 compared to the year before, according to the Atlantic Salmon Federation’s annual State of the Populations report, released June 11, 2018.

ASF is asking national government delegations gathered this week in Portland, Maine, for the summit of the North Atlantic Salmon Conservation Organization to take additional measures in their home waters, including minimizing or eliminating threats from open net-pen salmon aquaculture, preventing the harvest of salmon from threatened and endangered populations, and ensuring that all in-river fisheries are conducted sustainably.

“Overall, we are struggling to restore North American wild Atlantic salmon populations to sustainable levels,” said ASF President Bill Taylor. “Although there are some bright spots, areas where we are seeing the result of wise management, we must remain concerned about the suite of threats affecting oceans and rivers.”

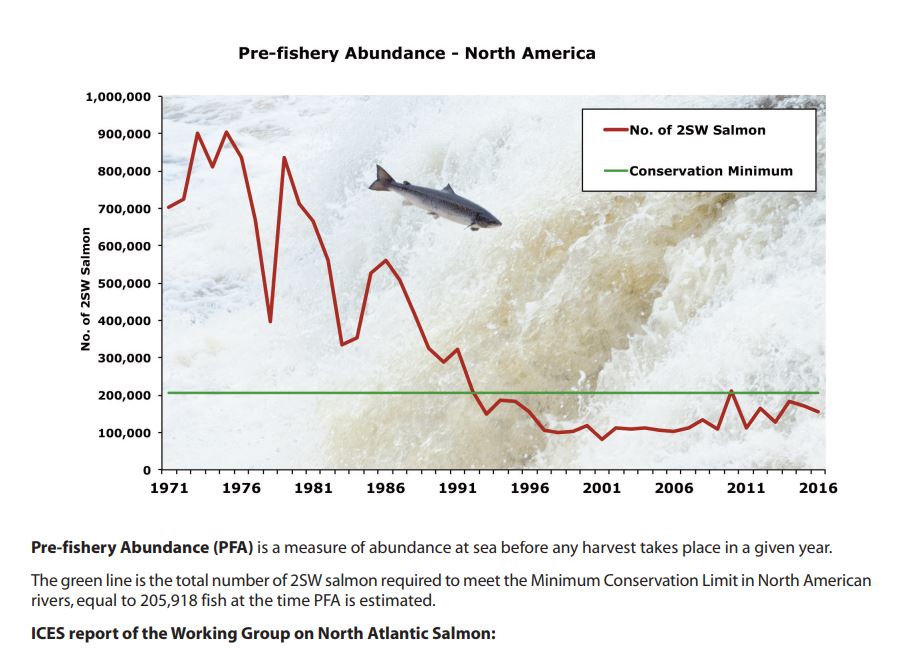

An estimated 496,000 salmon successfully spawned in all continental rivers last year, well below minimum conservation limits in some areas.

In the United States, where wild Atlantic salmon are listed under the Endangered Species Act, 1,041 salmon returned to all rivers in 2017, the vast majority (849) to the Penobscot River in Maine. The U.S. total represents an estimated increase of more than 400 individuals compared to 2016. Additionally, genetic testing from mixed stock fisheries at Labrador and Greenland revealed that, respectively, 1.1 and 1.4 percent of the salmon sampled came from American rivers.

In New Hampshire, as I’ve reported, we have pretty much given up on effort to get salmon to return to the Merrimack or Connecticut rivers. The ASF report says “In the Connecticut River had 20 salmon return in 2017, and the Merrimack River had 4 large salmon (meaning salmon that lived two years in the ocean, growing to full size) and 1 grilse, which is a salmon that returns after just one year in the ocean.”

In Canada, the total harvest by anglers (57 per cent) and indigenous fisheries (42 per cent) was estimated at 112 metric tonnes last year, a drop from 135 tonnes in 2016. This decrease can be attributed to a move by Fisheries and Oceans Canada to instate mandatory live release rules in Newfoundland last August, the continuation of live release angling in the Maritime provinces, and conservation measures by many First Nations.

The region with the largest year over year abundance declines in North America was the island of Newfoundland and parts of southern Labrador.

Conversely, rivers in Northern Labrador and Quebec remain relatively healthy. In Quebec, of the 38 rivers assessed last year, 32 met minimum sustainability requirements and 23 of those exceeded optimum egg deposition targets. Parts of Nova Scotia and New Brunswick also showed solid returns, particularly the Restigouche and Margaree rivers, but overall numbers still fall below historic averages.

Because of the recently concluded 12-year conservation agreement between ASF, our European partner the North Atlantic Salmon Fund, and Greenland commercial fishermen, the number of wild salmon returning to North America could increase starting in 2019.

“We’re grateful and have deep respect for the Greenland fishermen who have a sovereign right to catch salmon in their home waters, but have agreed to end the commercial component of their fishery in the name of biodiversity and conservation,” said Bill Taylor.

ASF’s State of the Populations report relies on public data from Fisheries and Oceans Canada and the International Council for the Exploration of the Sea, a scientific body contracted to provide unbiased fisheries advice to governments including Canada and the United States.

Return to the Concord Monitor

Return to the Concord Monitor