Many of you reading this have in the past year or two allowed a spy or a bad guy to settle happily into your home, using it as shelter for unpleasant activities. But unless you’re a lot tech-ier than me, it’s hard to realize this, and harder still to stop it.

IoT Watchdog to the rescue! Maybe.

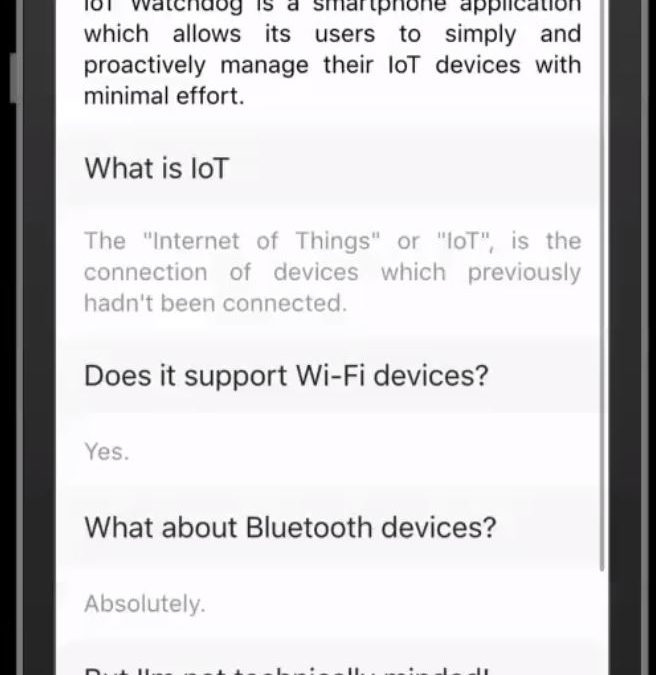

IoT (as in Internet of Things) Watchdog is the name of a smartphone app being created by Steve Castle, a software developer who lives in Lee. Appalled by the rolling disaster sometimes called the Internet of Insecure Things, he is creating a way to help clueless users like you and me spot and fix security holes in the connected devices that we’re buying like crazy.

Castle just received $25,000 from the Federal Trade Commission for the project, after winning a national competition “seeking tools to help consumers protect the security of their Internet of Things devices.”

And there are lot of those devices.

The problem is that the ecosystem of internet-connected webcams, routers, thermostats, speakers, baby monitors – even toasters, for crying out loud – lacks standards and practices to keep out hackers. It’s as if cars were sold without any door locks and with switches inside the glove compartment labeled “Top Secret Method To Hotwire Vehicle.”

It’s not hard for bad guys to sneak into our home network and slip malware into the devices. Sometimes they use the malware to prank people (scaring you by speaking through the baby monitor is popular) or to spy on folks, but more often the devices are turned into an army of robots, known as a botnet, that can send out spam or a massive denial-of-service attack.

Last October’s attack, which temporarily crippled Dyn, the online-services firm in Manchester that is now part of Oracle, is an example. It was launched from millions of internet-connected webcams and DVRs that had been secretly taken over.

The problem is so bad that the FTC has taken action against a couple of big manufacturers – D-Link Corp. and ASUS Corp. – forcing them to improve security for routers, wireless cameras and other devices, and the issue has become a big topic of study for Dartmouth College’s Institute for Security, Technology and Society and UNH’s InterOperability Lab. It was also the topic of January’s Science Cafe N.H. held in Nashua.

The idea behind Castle’s IoT Watchdog app is to help you and me reduce the problem by first figuring out what devices are connected to our home network, which of them have weaknesses and which can be fixed by things like downloading firmware or changing passwords.

Although it’s still in alpha mode, IoT Watchdog is pretty straightforward. When your phone is connected to your home network via Wi-Fi, you run the app, give it a little information about your router and follow the instructions.

“The way I approached this was to make sure it could get as automated as possible and provide as much information as possible in not-technical ways,” Castle explained. “My grandparents are both in their 80s – I would say: How would they understand this?”

Developing IoT Watchdog involves incorporating technical details like ARP caches, IP address lease tables and device data compiled by IEEE, but that’s not the hard part, Castle said. The hard part is getting up-to-date information from the hundreds or maybe thousands of companies that make IoT devices to create “fingerprints” of each device that the app could use to assess their vulnerability.

Vendors are unlikely to be enthusiastic about this, presumably because it could make them look bad – especially if there’s a vulnerability that has not yet been fixed – a real recipe for consumer backlash.

“That would leave the user helpless,” Castle said. “They would have been helpless before, but now they know it.”

Populating the app with enough device-specific information to make it truly useful will require more time and effort than a lone software developer can do, even with the FTC funding, Castle said, but winning the contest may draw attention and support.

In the meantime, you and I should make sure we’ve changed the password on our home router and any other connected device away from the factory default, if that’s possible.

This raises an ancillary question that Castle and I discussed: Whose fault is this?

I said it was the manufacturers’ fault for irresponsibly selling devices that are staggeringly easy to hack. Why is it even possible to connect a device without changing the default password? It’s a no-brainer to require a reset before start-up.

Not so fast, Castle said. He argued that consumers have to bear some of the blame.

“There’s a massive tradeoff between convenience for the end user and security,” he said. Customers go for convenience every time.

We refuse to be bothered by something as simple (although admittedly irritating) as resetting a password, let alone updating software or configuring devices, and we flock to the devices that don’t require it. Since we don’t see any drawback to security problems – there’s no cost to me if my router is being used as part of a botnet, for example – we won’t pay or do anything to solve them.

In short, he argued, it’s hypocritical to blame companies for leaving out features that I refuse to buy, and I can’t really disagree. My laziness (and yours too, I bet) has contributed to the problem.

Help me, IoT Watchdog!

Return to the Concord Monitor

Return to the Concord Monitor