First, the final story

HUDSON – The mystery of Alvirne High School’s world-record, 320-foot-long slide rule from three decades ago has been solved, mostly. Only one question remains: Where is it now?

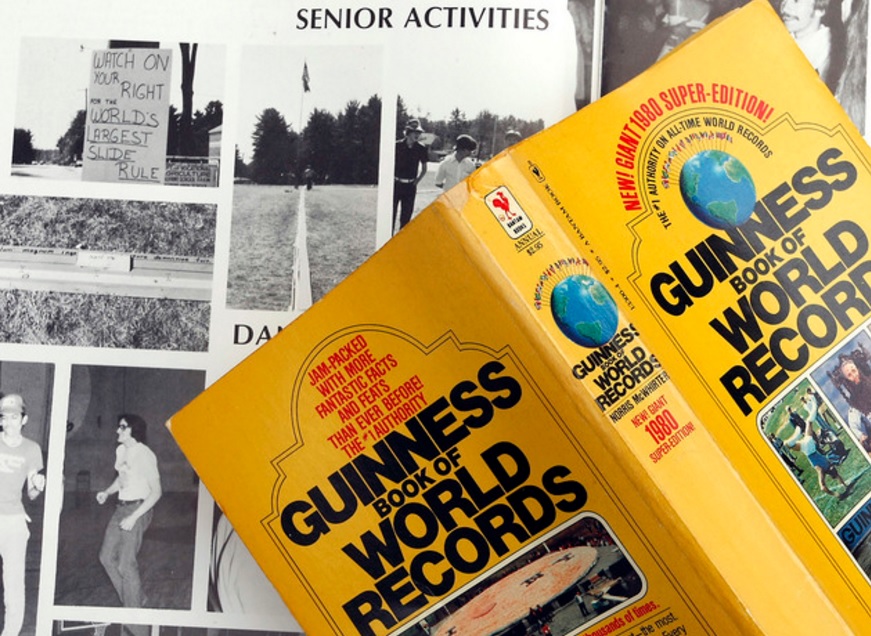

After the enormous, wooden contraption was laid out in front of the school on a crisp March morning 31 years ago, proving to be so long that students had to change the calculation so they wouldn’t block the driveway; and after The Telegraph had published a picture of it, so the Guinness Book of World Records would acknowledge Alvirne’s work in the 1980 edition; and after the school’s senior class had celebrated their accomplishment by taking their own pictures for the school yearbook – after all that, what happened to the slide rule?

Pedro Perez kneels and checks the workings of a 320-foot-long slide rule in front of Alvirne High School on March 22, 1979.

“One time I saw the center piece, one 8-foot section, down in the basement of what used to be the old historical society, but I don’t know for sure,” said Pedro Perez, who was a senior in 1979 when he instigated the project. “We were frugal. I seem to recall the remaining sections were returned to the shop as stock.”

Alas, says Hudson Historical Society member David Alukonis, no portion of the device ended up with the keepers of town history as far as he knows. And Alukonis should know, because he was a member of the 1979 senior class, and is even featured in The Telegraph’s photograph from that era.

“Maybe it’s in a barn somewhere, but I’ve never encountered it,” Alukonis said Monday.

Memory of this most unusual senior project had faded over the decades, but it returned last week for an unfortunate reason: The death of Jim Reed, who was an industrial arts teacher at Alvirne for 32 years.

Reed passed away April 11 at age 79, and his obituary for The Telegraph mentioned his role in creating a world record slide rule.

This intrigued the paper and led to a story in The Sunday Telegraph that detailed an inability to find out much about this project. That story drew the attention of Debbie Hanks of Hudson – who was Debbie Cuthbertson when she helped with the project as an Alvirne senior – and she contacted Perez, who is now a nuclear engineer in Virginia.

“My class, a couple of the seniors, we were looking for something we could do to get some recognition to the school,” Perez said. Alvirne had only opened a couple of years earlier. “We wanted to do something unusual, at the same time reflecting science and technology.”

Even in 1979, the calculating devices known as slide rules were becoming outdated, as the first handheld electronic calculators showed up in workplaces and schools. Not even centuries of being an obligatory tool of scientists could save the “slipstick” from eventual irrelevance, but in 1979 they hadn’t quite disappeared, particularly if your father was an engineer.

“I remember my dad using one,” said Hanks.

Perez, whose father was a civil engineer who worked for the company that built the Seabrook nuclear power plant, has similar memories. So when he learned that the world record slide rule was “only” 204 feet long, he decided to try to break it.

Perez said Mr. Reed took the weird idea in stride and gladly helped the senior design, build and assemble 40 separate 8-foot-long sections, made from ripped wood stock in the machine shop.

“He was very supportive. We became good friends,” said Perez of the teacher. “A lot of the work we had to do after school – and he would stay with us, because you could not let the students (in the shop) unsupervised.”

The result, Perez admits, was not a model of calculating accuracy.

Slide rules use logarithms to simplify calculation. Longer slide rules can hold more detailed logarithmic marks, allowing more detail in the answer. A standard 10-inch slide rule is accurate only to three significant digits but the current world record, a 350-footer made by a retired engineer in Texas, can do calculations to six significant digits.

In theory, the Alvirne rule could also have been that accurate, but the markings were drawn on a long, long roll of cash register tape affixed to the wood on its record-breaking morning, and Perez said they were only sufficient to do a simple multiplication.

More precision wasn’t possible, Perez said, partly because it was tough getting high school seniors overly concerned about niggling details when graduation was barely two months away. After all, this was happening too late to be included on college applications.

“We were a pretty geeky class,” said Hanks. Among other things, she said, they successfully petitioned officials to create a Latin course.

The slide rule might not have been a thing of calculating precision, but it was impressive to behold, Alukonis said: “I remember how it took up the whole front lawn, from one end of the building to the other.”

Perez says he had planned to use it to calculate 3 times 2, but that involved extending the sliding portion so far that it would have blocked the driveway. He made a last-minute change, which was easier said than done: The slide rule was so unwieldly that it took a half-dozen people, each dragging a dowel handle, to shift the slider.

“We had to precisely align the numbers on the scales, and just to move something that 320 feet a couple of inches, coordinating all those folks pushing at once, wasn’t easy,” Perez said.

It was enough for the Guinness folks, who included a listing about the accomplishment in the 1980 book of records.

A group of college students in Illinois built a 323-foot slide rule later that year and bumped Alvirne from follow-up editions of the Guinness records.

The Telegraph published a photo in its March 22, 1979, edition, showing Perez and others working away – it was headlined “The Long, Winding Slide Rule” by some Beatles fan of an editor – and the rule itself was left on the front lawn for several days.

After that, who knows? High school graduation swamps the memories of those involved. Nobody recalls taking it apart, but presumably Mr. Reed oversaw the work, and if any piece was saved, he might have saved it. His family members say none of them know anything about it.

Incidentally on the back of the slide rule, written by Hanks at Perez’ request, is a quotation in Latin from the poet Seneca that sums up the class’ adventure. Translated into English, it reads “There is no great genius without some touch of madness.”

Here is the earlier story, from three days before (April 18, 2010):

News stories don’t usually carry titles like a detective novel, but this article certainly could: The Mystery of the Enormous Slide Rule.

That truly gigantic creation – as long as a football field – was built in 1979, just as slide rules were being made obsolete by electronic calculators.

It was constructed by what was then known as an industrial arts class at Alvirne High School under the direction of James Reed, a former teacher and department head who died April 11 at age 79.

“They had it on display in front of the school,” said his son, James Reed II, of Londonderry.

The younger Reed, who was a junior at Alvirne at the time, remembers that the project was initiated by “a young man from Cuba named Perez; I forget his first name.”

Reed’s father helped build the slide rule, including putting down properly spaced markings that allowed accurate calculation and installing the sliding “cursor” used to find answers.

The slide rule, so the story goes, was 320 feet long. Considering that real slide rules are rarely longer than 18 inches and that an expert in oversized slide rules contacted by The Telegraph has never seen one longer than 4 feet, this boggles the mind.

Reed thinks it stayed on display for a week or so and then disappeared. He isn’t sure what happened to it; it certainly hasn’t been stored in the family house.

The elder Reed was so proud of the project that he had it listed in the 1980 Guinness Book of World Records. It didn’t hold the record for long – an Illinois college built one 3 feet longer before the year was out, and these days the record is 350 feet – but it’s still impressive.

So, why do we call it a mystery?

Because when The Telegraph asked around, we couldn’t find anybody who knows where the behemoth went, couldn’t find anybody with a picture of it and aside from the younger Reed, couldn’t find anybody who remembers anything about it.

“I specialize in long-scale slide rules and collecting them … and I don’t know anything about this,” said Edwin Chamberlain, of Etna, a board member of the Oughtred Society, an international group of slide rule aficionados.

Most people younger than 40 have never even seen slide rules, which were the hallmark of engineers and scientists from the 17th century until the microchip dethroned all things analog.

Slide rules use the mathematical entity known as the logarithm to simplify math problems and allow for quick, complex calculations – for example, you can do multiplication simply by adding.

Their big drawback is that they lack precision. The standard slide rule can give answers to only about 1 percent accuracy, which was close enough for most engineering work until the space age needed more detail, said Chamberlain, a civil engineer.

Longer slide rules are more precise, which is why extra-large versions were sometimes built, as well as circular and spiral versions.

It isn’t clear how much detail Alvirne’s slide rule had. In theory, its size means it could have been 1,000 times as precise as a normal slide rule.

On the plus side, slide rule fans say the device’s advantage is that it requires the user to determine where the decimal point goes, forcing people to have a deeper understanding of problems.

“This new generation, I call them the button pushers,” said Skip Soldberg, a retired engineer in Texas who built the current world-record slide rule in 2001.

“They push buttons and they call it the answer, but don’t have a clue if it’s even in the right ballpark. They don’t know how to estimate the answer before you get the answer.”

Soldberg’s creation – so big that it can give answers to six significant digits, or 1/10,000th of 1 percent – is stored in his garage in 44 8-foot sections. If anybody tries to break his record, he says, he’ll just lengthen it.

Soldberg also has a collection of old copies of the Guinness record book. Unfortunately, his collection is missing the year 1980, when Alvirne’s slide rule was listed.

So, while Soldberg has books listing the 204-foot slide rule built by two Utah men prior to 1979 and the 323-foot rule built at the University of Illinois College of Law after Alvirne’s effort, he has nothing in between.

“I know about the Illinois one, but not yours,” he said.

No public library that The Telegraph contacted Wednesday has a copy of the 1980 Guinness book, and the book’s Web site doesn’t list its old records. Attempts to contact the firm in England were unsuccessful.

As for The Telegraph’s archive, the only mention we could find Tuesday – searching pre-digital newspapers isn’t easy – was a passing reference in a small 1980 story about attempts to set a different record at the Hudson school. That article said only “students set the record for the longest slide-rule last year.”

Otherwise, the Alvirne record is listed on a Web site called The Slide Rule Guy, which hasn’t been updated in a couple of years and didn’t respond to queries.

The site lists several record holders, including: “320 feet 11.1 inches in length completed in March, 1979, by students of Alvirne High School, Hudson, New Hampshire.”

Alvirne’s article on Wikipedia mentions the record, but without a verifiable source. As is common when something makes it onto Wikipedia, you can find many copies of that article scattered around the Internet.

So, the mystery remains: Did the slide rule really work? What was it made of? What did it look like? And what happened to it?

None of this should reflect on Reed, who was at Alvirne for 32 years. He was voted teacher of the year in 1974 and helped rebuild the school after a fire.

“He was a nice man, like a father figure to the kids,” said Kathy Vallaincourt, administrative assistant in the Hudson superintendent’s office, who knew Reed as a student and as a co-worker.

But it does raise an interesting question: How can such a huge, unique project disappear from storerooms and memories? That’s something that not even a slide rule could calculate.

Return to the Concord Monitor

Return to the Concord Monitor

Did the slide rule really work? Yes.

What was it made of? Wood. The main ‘frame’ was a pair of 1×6 planks with 2×1″ lathe cross-peicese, that were both glued, and screwed in place – I believe there were cross-straps every 2 feet. On the ‘High’ end of each 10′ section, the cross-strap was wider, maybe 6″, becasue that was the way the sections would overlap and be screwed together on the Big Day.

The slide was also 1″ thick plank, ripped lengthwise to only 4″ wide. Even still, the 320′ of slide was so heavy, it was hard to coordinate the senior class to operate the slide.

What did it look like: Painted yellow. Not terribly pretty. Major log markings were started in black paint, but that was going to take days to letter the scale, so we switched to magic marker, with fine-scale markings in ball-point pen. Pedro used a very long paper tape to transfer the scales, I don’t know how/where he inscribed the paper tape to begin with.

Where did it go? Lumber is not free, and we needed sponsors. So after we disassembled the sections, the center section went back into the wood shop to hang on a wall. But 5 or 6 of the sections were delivered to some of the Hudson businesses that donated to “Put Hudson on the Map”. Each section has its own story, from there. The remainder of the construct was, frankly, a storage problem, and so I’d be astounded if the wood shop did not scavange sections for other projects. I hope so, at least.

The 4 main collaborators on the scheme, we called ourselves Los Primos, (cousins) because I think 3 of the 4 met over summer-session Conversational Spanish class, and the 4th, ringleader Pedro Perez, was Cubano by birth:

Pedro Perez – Did everything

Marty Marshall – Promotion, fund raising, assembly,

Dave Alukonis – Pulled way more than his own weight in gluing/screwing the sections together, driving/lugging materials

Keith Pedersen – I was the least-productive member, on account of having basketball practices and games, meant that I only got down to the woodshop about 5 times. It took a LOT more work than that, to lay all the sections. The day of the assembly, we worked frantically with the help of Debbie Cuthbertson, I think maybe Holly Merrifeild, Luanna Reed, a group of girls I think of as ‘the library crowd’, were instrumental for the first 3 hours – then in the early afternoon, the senior class was let out of class to help us finish it off and do some calculations.

Amazing, almost 40 years later. I stumble on this from my home now in France. My good old friend (primo) Keith has a wonderful memory. The late Jim Reed made it all possible.

Keith forgets that it was he with me at my parent’s house tanscribing the log scale to paper roll the evening before our debut. We then took the paper roll on top of an assembled slide rule on a cold March early morning and wrote the log-scales for C-D only and on the school lawn – no time left. It was wonderful then and it is still vivid in my mémoires; but not the slide rule, it was our friendship.

Hi Pedro, I stumbled on this myself, looking for something else! I’m not sure if you will ever see this, but I figured I’d try anyway.

It has been quite some time since our days @ UML, and I hope that you are doing well. Drop me a line if you see this.

Take care,

Jim

Man, that sounds like a great project.

I used a slide rule in high school, probably the last group to do so. I took a TI SR-50 to college, but I always brought that Pickett 905-ES for a backup – if the battery died!

I know Skip Solberg through collecting old slide rules and he runs a slide rule contest every March during an annual “Antique Science and Retro-Tech” Show here in Bedford, Texas.

I’ll keep an eye out for a 1980 Guinness Book.

I never figured out the slide rule thing… maybe it was because I was likely chasing girl’s and drinking beer in our senior year in 1979. And of course, I was not half as smart as my classmates who designed and completed the project. I do recall going out and checking it on a cold New England afternoon with my fellow classmates of 1979. I graduated with an exceptional group of classmates.

I am so happy to have stumbled upon this article. I was in that graduating class of 1979 and have only fond memories of all involved. I wasn’t part of this project, but I sure did admire how smart and dedicated you all were to get it done. How is it possible this was over 40 years ago?! I agree with Mike LaVoie – it was an exceptional group.

’79 was One of a Kind!