A digital tool that uses patients’ medical histories to help predict whether they are susceptible to opioid overdoses has been approved for use in New Hampshire, joining long-established surveys that try to predict whether patients will become addicted to the painkillers.

But none of these are perfect, a reflection of the difficulty of determining the effect of opioids on individuals.

“There are some things that you just can’t measure. Even if we’re talking about measuring pain, the only tools we have are subjective,” said Dr. Gilbert Fanciullo, former head of the Dartmouth-Hitchcock Pain Management Center. “Someday we’ll be able to do something like a functional brain scan – their brain lights up and you say, oh, we should never give this person opioids again – but not now. … There are just too many other variables.”

For years, medical providers have used patient surveys to judge how likely someone is to become addicted to opioids. Some have been approved for use in the state by the New Hampshire Board of Medicine, including the Opioid Risk Tool and Screener and Opioid Assessment for Patients with Pain.

They ask patients to report certain things about themselves that are associated with addiction, such as whether they smoke cigarettes, whether they have been arrested or whether they have a close relative with addiction problem.

“Another part of it is that some patients get taken aback and are suspicious of you for asking some of these questions. If they’ve been released from jail – if they’ve paid their debt to society – they can be very insulted if you ask questions about it,” Fanciullo said.

The new product, approved last month by the New Hampshire Board of Medicine, takes a very different tack. It gathers the data automatically from medical records, requiring no input from the patient or practitioner, and it tries to estimate not the likelihood of addiction, but the likelihood of accidental overdose.

“Almost all the existing tools focus on abuse or addiction … but there’s a very large percentage of opioid-using patients that are ignored and who can be at very high risk for overdose,” said Mark Tripodi, the company’s chief development officer.

Called the Venebio Opioid Advisor, it is made by Venebio, a Virginia-based startup. The product takes data on a patient’s medical history from existing records and, based on analytics of demographic data, medical results and other factors, estimates the overdose risk for the medical provider to consider as part of treatment.

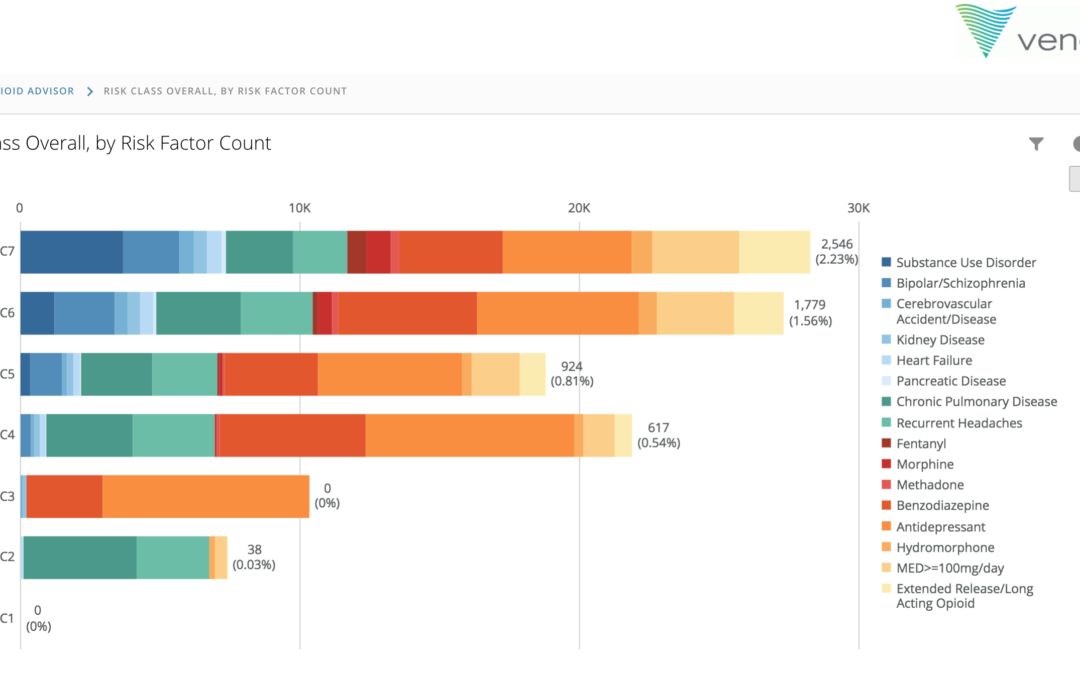

The software uses eight diagnosis categories, Tripodi said: “Some are what you’d expect, such as substance-use disorder, but there are other things like bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, heart disease, pulmonary disease” that can have unexpected correlations with reaction to opioids.

The software also calculates the effect of any current treatment in the patient’s record, since certain medications, such as some antidepressants, can raise the risk of opioid overdose.

Instead of just giving a single score ranking overall risk, Tripodi said, Venebio “gives the reasons for a patient’s risk, what’s driving it, which can be different for each patient” and then provides some recommendations for the provider to consider.

These include taking a look at existing medications and at the opioid dosage, to see whether the provider wants to change either.

“Even in cases where maybe there’s nothing to be changed … or the therapy is what it needs to be and there’s a high risk of overdose, the physician can always order Naloxone and send them home with it, to have in an emergency,” he said.

Naloxone is the quick overdose-reversal drug often known by brand name Narcan.

The software was approved for use by New Hampshire providers last month. Tripodi said New Hampshire is unusual in requiring such approval.

The Venebio Opioid Advisor launched last fall. Tripodi said it was being used by some regional Medicaid systems and would soon be adopted by a national chain of independent pharmacies, allowing the risk assessment to be created for pharmacists and then shared with the person’s provider.

Tripodi said the cost was “pennies per patient.”

Return to the Concord Monitor

Return to the Concord Monitor