Stop me if you’ve heard this one before: Out-of-state company wants to build a big energy project. Some people object, some celebrate. Media get involved. Fight ensues about state regulation versus town control. Meetings are held, money is spent, egos are bruised, votes are taken. The big energy project dies.

No, we’re not talking about the defunct Kinder-Morgan natural gas pipeline or the first Antrim wind farm, not even the Northern Pass transmission line, where the ending is far from decided.

This was a wilder idea: Build an oil refinery on the shores of Great Bay in Durham, connected by an underwater pipeline to an oil tanker docking station on the Isles of Shoals. It was proposed by the richest man in the world and backed by the most powerful men in the state, but within two years it had been killed due mostly to a trio of not very powerful women.

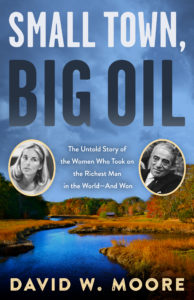

The story is told in Small Town, Big Oil, a lively, just-released history by David Moore, an award-winning author and a senior fellow at the Carsey Center for Public Policy at UNH.

Moore, who lives in Durham, was prodded to write the book after a Durham Historical Society shindig marking the 40th anniversary of a March 7, 1974, vote by the state Legislature at a special session. That vote gave local communities rather than the state’s siting energy committee final say in whether an oil refinery could be built, and basically killed the project. Before then, it wasn’t clear who had jurisdiction because state laws hadn’t anticipated an oil refinery.

The obvious one for New Hampshire is balancing state versus local decision-making in the location of big energy projects, where the benefits are widespread but the pain is local. It comes up with every wind farm, pipeline and power line that gets proposed.

“It’s an ongoing conflict, and I don’t think you’ll ever see an end to it,” said Moore. “No parallel is perfect, no analogy is perfect . . . but it has a lot of lessons about the ever-present conflict between local and state authorities.”

Northern Pass opponents haven’t been shy about claiming parallels, saying that the oil refinery’s defeat shows they should be allowed to defeat the transmission project, although the legal situation is not quite the same.

Gov. Thompson and an ailing Aristotle Onassis try to sell the refinery at a NH press conference. Onassis died the next year.

There are other echoes of today’s news in the story, as well. One is the angry opposition that can arise when women take aggressive roles in public life.

The refinery opposition was headed by a Seacoast environmental activist, Nancy Sandberg; a young state representative with the intriguing name of Dudley Dudley; and Phyllis Bennett, who published Publick Occurrences for two years until it folded for financial reasons.

This didn’t go over well with everybody. The Union Leader’s bomb-throwing publisher, William Loeb Jr., a vocal refinery supporter, infamously called the opponents “little ladies . . . vainly beating their small breasts.”

“You see that today, the impact that women can have on society. It’s the women who are organizing. Not that the men don’t help, but the women are not the subordinates, they are the leaders. In the environmental area in particular I think you’ll find large numbers of women, maybe more so than men, leading the movement,” said Moore.

Another parallel is the ability of a free press to hold huge institutions accountable even when struggling with financial problems.

As Big Oil, Small Town makes clear, the refinery idea came to light only because of Publick Occurrences, a tiny, young Newmarket weekly newspaper named after the first newspaper printed in America. Its staff heard rumors that lots of land was being quietly purchased in Durham and ran with the story when bigger publications, including the Monitor, shied away; otherwise the oil project might have been a done deal before anybody caught on.

The idea of a refinery and oil terminal on New Hampshire’s Seacoast was proposed by Greek oil magnate Aristotle Onassis, who is better remembered today as Jackie Kennedy’s second husband. It was seized on with glee by publisher Loeb, whose Union Leader had far more heft than newspapers do today, as well as his favorite politician, the fiery Gov. Meldrim Thomson, then in his first term.

The idea didn’t sound quite so out-of-the-blue in 1973, when the first OPEC oil embargo and resulting gas crisis made petroleum-related development desirable. The other five New England states, in fact, had talked about cooperating to build a refinery.

And while Small Town, Big Oil isn’t shy in celebrating the way the story ended, since a refinery in the estuary of the Great Bay would have been an environmental disaster, Moore notes that the issue isn’t always so clear cut.

“There are some activities that require the state to have the authority to establish,” he said.

Return to the Concord Monitor

Return to the Concord Monitor

Same thing almost happened at Sears Island, a 1 mile by 2 island in Penobscot Bay off Searsport, Maine. First proposal was for a nuclear power plant. Opposed by the Sierra Club and others. That battle went on for a few years before being abandoned. Next was an aluminum smelting plant, also opposed by the usual organizations. After that, a container port was a sure bet. Surprise, that also failed. Now, the island (I think) has a few homes on it with the rest is a park or saved woodlands. I haven’t been back in a while.

My father was for all these projects with the promises of jobs for all the young people who had to move away to make a decent living. It was a while before I knew that “Damned Environmentalist” wasn’t one word. He changed his mind late in life, especially with me going into the wind and solar industry.

Have not read the book, and will, but sure hope it also discusses the battle in Newmarket,NH over the same issue. My father was a Newmarket Selectman at the time and the Select Board held meetings with Onassis about building in Newmarket once (as my memory serves, and I was quite young at the time) Durham had said no. The issue was incredibly divisive in Newmarket, which knew that its textile mills were dying, and was looking for a way to sustain its economy. My memory tells me that Newmarket ended up not being big enough for the project, thank goodness.

Newmarket and Durham were very different types of towns– the former a mill town, the latter a university one– (a whole other book could be written about that) so I do hope that the Newmarket part of the equation was covered in the book.

Karen

My grandfather was a state representative at the time and he was opposed to this refinery. My aunt Lola went around the town knocking on doors to get people to oppose this. I am glad all the efforts by many were successful. At the time I was in the U.S. Army and stationed in West Germany. I flew home for a week in part to tell my grandfather that I opposed this project. Sincerely, Rodney.